Zero Woman: Red Handcuffs

- Year

- 1974

- Original title

- Zero-ka no Onna Akai Wappa

- Japanese title

- 0課の女 赤い手錠

- Director

- Cast

- Running time

- 85 minutes

- Published

- 28 September 2011

by Tom Mes

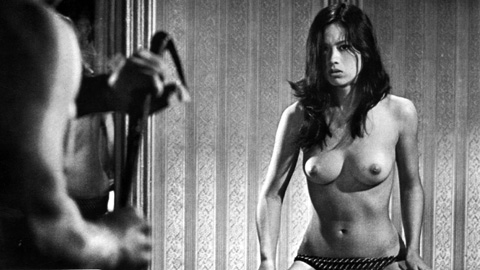

Although it springs from the same fertile imagination as Female Convict Scorpion - that of manga artist Toru Shinohara - and it features a similar sexy/deadly heroine, Zero Woman: Red Handcuffs shoves the carefully maintained balance between sensationalism, surrealism, and feminism of the Meiko Kaji-starring series brusquely aside. With luscious, pouty-lipped Toei Pinky Violence actress Sugimoto in the lead, clothing is shed as frequently as the plot will allow, which is to say rather often. And while she possesses precious little of Kaji's smouldering charisma, it must be said that Sugimoto is not at all lacking in charm.

The plot of Zero Woman was resurrected twenty years later for Luc Besson's La Femme Nikita: wildcat is saved from the gallows and forced to become an agent for the top secret Division Zero of the Tokyo police department. Armed with a gun, a badge, and a pair of handcuffs that are all as nail polish-red as her skin-tight leather outfit (when she wears it), she is sent to investigate the kidnapping of a politician's daughter by a gang of psychopathic thugs (led by Go, the real-life younger brother of Nikkatsu old boy Jo Shishido). After infiltrating the gang, she stoically endures several rapes by its members to win their trust and then begins to imaginatively eradicate them one after another in her search for the missing girl.

Though some have referred to this film as feminist, it is more a case of having your cake and eating it too. This results in a generous and oh so satisfying helping of seriously stylish sleaze, with Sugimoto making up with her physical presence what she lacks in other departments (though it must be noted that in addition to her more generic work for Toei, she also appeared in several films for New Wave bastion Art Theatre Guild before retiring from film altogether at the end of the decade). There are some attempts at injecting deeper meaning on the part of director Noda - note the references to the infiltration of American pop culture, reminiscent of the Meiko-Kaji starring Nikkatsu actioner Stray Cat Rock: Sex Hunter - but for the most part this is exploitation as exploitation was meant to be. And in that department, it comes with the highest possible recommendation.

Like Female Convict Scorpion, Zero Woman was revived in the 1990s as low-budget straight-to-video fodder, and not entirely unsuccessfully. In an example of cinema’s inherently transnational nature (not to mention a great deal of irony) the idea to dust off the concept of Noda's film was most likely influenced by the international success of the aforementioned La Femme Nikita, a film that made female assassins a temporary hot topic and spawned remakes, official and otherwise, in the USA (the Bridget Fonda starrer Point of No Return) and Hong Kong (the Black Cat series), as well as a long-running TV series. Zero Woman was Japan's attempt to jump onto the bandwagon, adding more than a touch of S&M (in what could be read as a nod to the delightfully insane ero-guro works of Teruo Ishii, the first straight-to-video Zero Woman pits its heroine against a bondage-fetishist dwarf in a torture dungeon) but little in the way of inspiration.

In a dizzying game of multimedia mise-en-abîme, the Zero Woman remake not only spawned a host of sequels - the best of this bunch being Zero Woman IV: The Accused - but created an entire subgenre of straight-to-video 'female action' flicks featuring gun-toting, scantily-clad ladies, whose most famous entries are the Prisoner Maria series and Metropolitan Police Branch 82 (also based on Toru Fujiwara's work). Even Takashi Miike got in on the act, directing the pneumatic but bland topless model Atsuko Sakuraba in the thankfully little-seen Silver (1999).

Whereas Zero Woman's many sequels (seven entries to date) were all shot on digital video, the first instalment was recorded on 16 millimeter. Ironically, most of the video sequels ended up looking better than part 1, which is marred by drab cinematography.

The Zero Woman series briefly acquired a minor cult following outside Japan after the films were released on video in the US in the late 1990s. Given the limitations of the concept and its inherently exploitative execution, recommended viewing in this series are parts 3 and especially 4. Yukio Noda's original, however, leaves them all trailing far, far behind.