The Sun’s Burial

- Year

- 1960

- Original title

- Taiyo no Hakaba

- Japanese title

- 太陽の墓場

- Director

- Cast

- Running time

- 87 minutes

- Published

- 9 March 2015

by Kohei Usuda

In retrospect, 1960 was a pivotal year for the launch of the Shochiku studio’s youthful brand of the Japanese New Wave cinema, also known by its eponym, the Shochiku Nuberu Bagu. Remarkably, that year alone saw the releases of Nagisa Oshima’s trailblazing second feature Cruel Story of Youth, a pair of early modernist masterpieces, Good for Nothing and Blood Is Dry by Yoshishige Yoshida, and Masahiro Shinoda’s notable début, Dry Lake. All were directed, astoundingly, by filmmakers under the age of 30.

The birth of the Japanese New Wave was made possible thanks to the ambitious policy implemented by Shochiku to promote its young assistant directors to the ranks of fully-fledged directors in their own right – a policy designed to counter the rising popularity of the television by injecting fresh blood into the country’s film industry.

All the films mentioned above were screened as part of the sidebar program entitled 1960 – The Time of Destruction and Creation at the 2014 edition of the Tokyo Filmex festival. Another was The Sun’s Burial, Nagisa Oshima’s little-known follow-up to Cruel Story of Youth and also released in 1960, which follows the squalid lives of the very poor in the slums of Osaka.

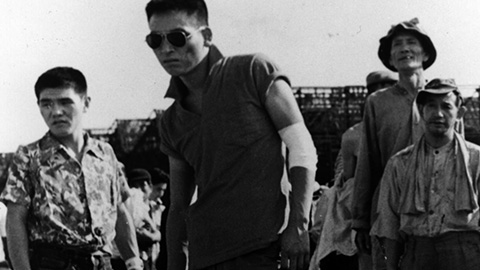

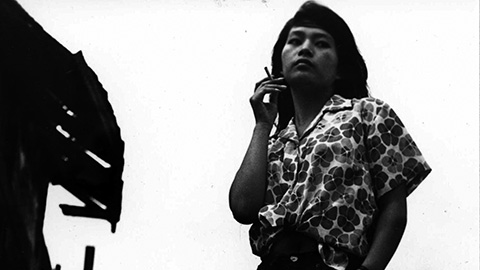

Set in the notorious Kamagasaki district (now renamed Airin-chiku), this third feature by the nascent iconoclastic director is an intensely charged drama, multi-character study about the dwellers of the ghetto living on their own terms in impoverished conditions on the periphery of society. The Sun’s Burial is populated by day-labourers, homeless war veterans, vagabonds, prostitutes, black-marketers, and small-time gangsters, some of whom resort to the illegal blood trade and even to robbery and murder.

In scene after scene, Oshima frames Tsutenkaku Tower in the background of the shot, an ever-present Osaka landmark constructed in 1956 in a more affluent and booming part of the populous Kansai city. A hideously designed architectural symbol of the nation’s growing prosperity, the Tsutenkaku is seen oppressively towering over the poverty-stricken have-nots, who live by contrast in the shadow of Japan’s "economic miracle" of the 60s.

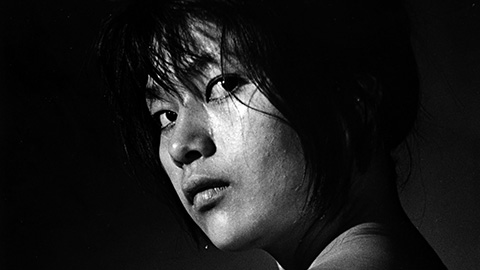

Though the then 28-year-old Oshima’s direction remains occasionally patchy and unpolished at this stage in his career – one must wait for the appearance of The Catch (1961) the following year to witness the signs of Oshima’s revolutionary aesthetics that would come to flourish later in the decade – The Sun’s Burial nonetheless possesses numerous flashes of brilliance as well as instances of exceptional beauty that seem almost inappropriate for a film that sets out to depict extreme poverty – namely, the slow dolly shot atop the hillside Shinto cemetery which overlooks the panoramic vista of Osaka’s skyline at dusk; here, three solitary figures appear stranded before the impressive scenery, in a shocking scene that is abruptly cut short by the death of one of the trio.

Not unlike Pedro Costa’s much later portrayals of Lisbon’s Fontainhas shantytown in films such as Ossos (1997), Oshima’s fidelity to Kamagasaki’s specific locality testifies to his firmly grounded stance as a politically committed filmmaker. He even juxtaposes his mise en scène with some 16mm footage documenting the real-life denizens of Kamagasaki toiling away in the ghetto.

Indeed, for Oshima, the act of making a film is determined precisely by his “attitude” towards a particular – and therefore limited – space. Hence, his choice to set his films within the perimeters of domains that are separated from the world at large, for example, the isolated village cut off from Japan’s war effort in The Catch, Tokyo’s vibrant and chaotic Shinjuku district in Diary of a Shinjuku Thief (1969), and the Shinsengumi militia’s walled-off Kyoto compound in Taboo (1999). With Oshima, such claustrophobic spaces can sometimes take the form, literally, of confined areas or prisons, as in the bare-bones execution room of Death by Hanging (1968), the Japanese-controlled POW camp for the Allied soldiers on the island of Java in Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence (1983), the British diplomat’s Paris apartment in Max mon amour (1986) where his wife keeps a domesticated chimpanzee as a lover. (From this point of view, the family’s cross-country odyssey in Boy [1969] that ends tragically on the northernmost tip of Hokkaido is highly atypical, given that Oshima’s oeuvre is generally devoid of mobility.)

In short, Oshima’s films can be said to be about captivity. Just as the lovers in In the Realm of the Senses (1976) become prisoners of their own passions as they explore the limits of love and pleasure in a series of ryokan rooms, so the poor in The Sun’s Burial are thrown together in the slums and left to their own devices.

Moreover, whereas his fellow Shochiku alumnus and New Wave luminary Yoshishige Yoshida specialized in the dynamic use of the monochrome scope format, what Oshima demonstrates in The Sun’s Burial – something already manifest in Cruel Story of Youth – is his skill as a "colourist" filmmaker. The Sun’s Burial is built around a colour palette consisting chiefly of shades of red. It is probably not an exaggeration to claim that the subject of The Sun’s Burial is the death – or burial – of the colour red itself, as is repeatedly illustrated across the film. (Red here being the obvious metaphor for the Japanese flag and its wartime variant, the Rising Sun Flag.) It is as if the entire film takes place in the hour of the setting sun, or else in the deep darkness of the night. What’s more, The Sun’s Burial concludes with a violent riot of fire and flames, culminating in the burning of the ghetto by arson at the hands of its own populace, an act that could be interpreted as the symbolic burial of the Land of the Rising Sun, thereby exorcizing, once and for all, the ghost of the Imperial Japanese Empire.

It is no coincidence, then, that Oshima stages a great murder sequence midway through the film, that is, the stabbing of one of the young members of Shinei-kai, the underworld criminal gang that rules the Kamagasaki enclave with brute force. He is played by Yusuke Kawazu in a rebellious James Dean impersonation, dressed, invariably, in a short-sleeve shirt of vividly bright Coca-Cola red.