Lesson of Evil

- Year

- 2012

- Original title

- Aku no Kyoten

- Japanese title

- 悪の教典

- Alternative title

- Lesson of the Evil

- Director

- Cast

- Running time

- 129 minutes

- Published

- 18 November 2012

by Tom Mes

When Sion Sono made his international breakthrough over the course of 2002 with Suicide Club, those few who had followed his career up until then could not help but notice a remarkable and sudden change of style and tone. Where Sono’s earlier work consisted largely of dreary indies about his ex-girlfriend, the lurid, blood-soaked and erratically plotted genre piece Suicide Club borrowed liberally and quite overtly from an approach to violence that Takashi Miike had been honing at least as far back as 1995’s Shinjuku Triad Society and which, more importantly in this context, had earned Miike his first worldwide exposure in the shape of Audition a mere two years earlier.

With Lesson of Evil, his lurid, blood-soaked and quite tightly plotted adaptation of Yusuke Kishi’s novel about a high school killing spree, Miike not only acknowledges the debt Sono owes him, he also exonerates his colleague by returning the gesture, referring and borrowing quite overtly from Sono’s recent output: two featured members of the film’s young cast are the award-winning lead couple of Himizu, Fumi Nikaido and Shota Sometani, while Cold Fish star Mitsuru Fukikoshi appears in an important supporting role.

This could be explained as coincidental, since it is after all only natural for actors to appear – occasionally alongside each other – in different films, an occurrence all the more frequent in the relatively tight-knit world of Japanese cinema. However, halfway through Lesson of Evil, Miike serves up a flashback/dream sequence that borrows so heavily from Cold Fish’s scenes of efficient serial killing and corpse disposal, that any notion of coincidence is swiftly banned from the mind. And that’s without mentioning the schoolgirls falling from rooftops. At least the recurring visual motif of crows is all Miike’s own.

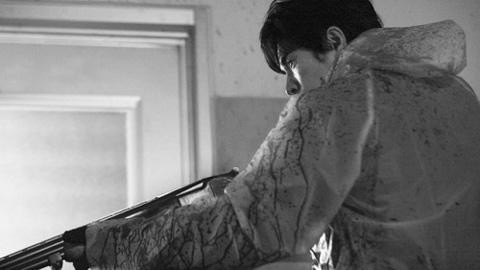

At the same time, the very violent Lesson of Evil also marks a departure from Miike’s previous cinematic explorations of the giving and receiving of pain: it disposes entirely with the glee and the mischief, replacing them with the calculated, heartless acts of a seasoned psychopath, filmed with an unflinchingly observant camera. Adding to the impact are the young age of most of the victims (the obvious comparison with Battle Royale goes limp on the dry shooting style, which contrasts sharply with Fukasaku’s baroque histrionics) and the central performance of Hideaki Ito, the square-jawed hunk of all those terrible Umizaru movies and also seen in Miike’s Sukiyaki Western Django, who here is pitch-perfect as the charismatic English teacher who charms his way into the hearts (as well as a few other body parts) of his students but hides a very dark secret. Indeed, in addition to the violence, the performances are a standout, in particular from the very convincing gallery of young talent, known and unknown, portraying the high school students.

Also worthy of note is the fact that Miike wrote the script for this film himself. Previously credited alongside other screenwriters on The Great Yokai War and the aforementioned Django, this is his first solo outing as a writer. Lesson of Evil could therefore be regarded as "his" adaptation, more than any that came before. This forms another departure, or a new chapter perhaps, and it is remarkable for two reasons: that the man known for taking liberties with narrative would deliver such a tightly-plotted film and that this goes hand-in-hand with a change toward an arguably tauter style of filming. Miike is known for having all his shots planned out in his mind ahead of a day’s filming, thus removing the need for storyboards, but on this occasion he has had more time to mull them over, and to mull quite profoundly.

It will be interesting to see how this increased control over the creative process will develop through Miike’s future works – and what the consequences will be on the films he makes. If he keeps up his infamous pace, he simply won’t have time to devote himself to each film the way he did to Lesson of Evil. Then again, this may well signal a change of that pace (although, with the increasing budgets of his increasingly mainstream projects, he was already down to two rather than four films a year). This being Takashi Miike, however, the only thing you know for certain is that you never know. Except that it will feature a few crows.