A Woman and War

- Year

- 2013

- Original title

- Senso to Hitori no Onna

- Japanese title

- 戦争と一人の女

- Director

- Cast

- Running time

- 98 minutes

- Published

- 16 February 2013

by Tom Mes

The inexplicable return of Shinzo Abe to the post of Japan’s prime minister does not bode well for anyone who holds dear to diplomacy and historical fact. As has been opined in various media, the LDP leader’s true agenda, at a time when economic stability and the danger of nuclear energy form his citizens’ main concerns, seems to be one of nationalism-fuelled revision: revising the famed Article 9 of the constitution and revising the official record of the nation’s wartime past.

One plus one may well add up to disaster. With Japan’s diplomatic relations with its main neighbour and economic rival China brought back to a boil in the wake of the Senkaku Islands controversy, and the utter lack of any sort of credible sensible political counterweight after the DPJ’s meltdown, tough times seem to be ahead.

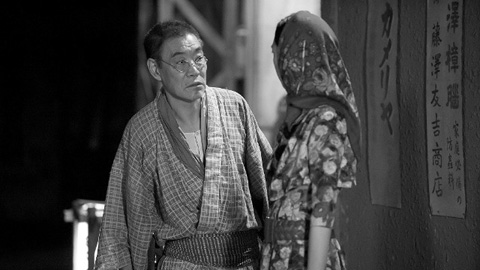

A Woman and War could, sadly, not have arrived at a timelier occasion. The Junichi Inoue-directed adaptation of Ango Sakaguchi’s novella is set in the last days of the Pacific War, as the population awaits a seemingly imminent Allied invasion of the Japanese mainland and what they believe will be an accompanying campaign of murder, rape and pillaging. Without any prospect of a future and shorn of basic daily necessities, most of the film’s protagonists have become desensitized: a former prostitute turned bar owner (Eguchi) who claims she is happy with the war because “it makes everyone equally unhappy”; a novelist (Nagase) who avoided the draft by agreeing to write scripts for propaganda films, though at the cost of a profound self-loathing; a soldier (Murakami) back from the front minus one arm and the ability to have erections.

One evening the bar owner declares to her handful of customers that she is packing it in and that she will marry the first man who will have her. The novelist, at the present married men’s insistence, agrees, and the two decide, in Realm of the Senses-like fashion, to shack up at his house and “screw until the war is over” or until they die, whichever comes first. The one-armed soldier, meanwhile, tries his utmost to settle back into family life, in vain. When he witnesses a woman being gang raped, he notices stirrings below the belt: after years of raping women in China, this is now the only way he can get it up. He commences luring women with the promise of a deal on affordable rice, after which he murders them and violates their bodies.

This adaptation of Sakaguchi’s book was initiated by film critic Ken Terawaki, a move that may seem surprising when one knows that Terawaki’s film writing has always been an activity on the side line of a long career as a bureaucrat in the areas of education and cultural affairs. It’s slight relief to know that not all those in positions of government share the hawkish hard line, but in this day and age we’ll take all the relief we can get.

While it may be hard to label A Woman and War as “relief”, among the vapid pap churned out by consortia of TV broadcasters, ad agencies and talent management, and the latest pathetic attempts to hoist Yoji Yamada to master status, this independently-produced scorcher hits the screen like a bomb blast of fresh, honest air. Director Inoue is no stranger to grass-roots subversive filmmaking, since he was the writer of Pure Asia (Ajia no Junshin, 2010), a tale of outcast school kids turned terrorists directed by Ikki Katashima, who in turn produced A Woman and War.

One imagines that production companies in Japan were not exactly lining up to finance A Woman and War. The resulting modest budget, however, ironically serves the film well: the absence of large numbers of extras helps render bombed-out Tokyo impressively lifeless and depopulated, its streets reduced to charred cesspools with a few odd corpses floating into view. This in turn makes the life that is present on screen all the more luminous: far from the traditional suffering heroine so beloved of (male) Japanese filmmakers, Eguchi’s bar hostess finds reasons to smile amid, and especially at, death and destruction, counterbalancing the novelist’s nihilism and even showing him improbable points of light. Impervious to disease, lice and other discomforts of wartime living (though also, it seems, to sexual pleasure) it is clear from the outset that she will endure.

While A Woman and War was made outside the narrow confines of the pink film industry, the film’s politically and sexually risqué nature (and the symbiotic combination of these two components) point to the shared past in pink film of several of the main names behind the scenes, particularly in its political offshoot. Both director Junichi Inoue and scriptwriter Haruhiko Arai spent years working at Wakamatsu Productions, while Arai’s co-author Futoshi Nakano worked extensively with members of the Seven Lucky Gods, the generation of pink film directors that emerged at the turn of the millennium, including Yuji Tajiri and Rei Sakamoto. Indeed, A Woman and War shares many characteristics and concerns with Koji Wakamatsu’s recent output (although it is thankfully bereft of their static, flat cinematography). It is – yes, after all – a relief to know that Wakamatsu’s fighting spirit lives on despite his recent untimely passing.