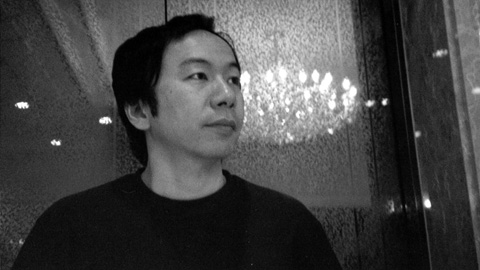

Shinya Tsukamoto

- Published

- 23 October 2002

by Kuriko Sato

One of the most important names in contemporary Japanese cinema, Shinya Tsukamoto has done groundbreaking work in arousing international attention for Japanese film. When his still powerful, independently made, black-and-white Tetsuo: the Iron Man (1989) toured an unprecedented number of festivals in the late 1980s and early 1990s, many western eyes turned eastward with renewed interest.

At home however, Tsukamoto has always kept a position in the margins. Despite doing the occasional, but always interesting, director-for-hire job (such as Hiruko the Goblin and Gemini), he has remained fiercely independent, nurturing his projects with complete devotion, and honing his unique and very distinct style.

The special jury prize his latest film A Snake of June (Rokugatsu no Hebi) received at the 2002 Venice film festival once again showed how enamoured western film buffs are with the work of Shinya Tsukamoto.

You had the idea for the film A Snake of June even before you made Tetsuo. Why did it take you so long to realise it?

It's true that I wanted to make this film before Tetsuo, for about fifteen years in fact. Every year in June when the rainy season started, the wish to make it would creep up inside me. That season in Japan is very hot and humid, which inspired me with regards to the film's element of eroticism. But when the summer would come around, I would lose that motivation. Until June of the following year, when I would get motivated again. I would repeat that cycle over and over because I don't write screenplays so quickly. I would get the motivation in June, but I would still be thinking about it by the time the summer came around.

The original idea I had was different from the film as it exists now: more violent, more pornographic, and more immoral. Over the years, elements from this idea found their way into the other films I made. Recently there has been a tendency to make intellectual erotic films, in France for instance. I felt I couldn't miss the opportunity. If I waited even longer it might be too late. Now that I've finally made it, it feels like I've completed a life's work, like I've closed a chapter.

Why did you want to make a pornographic film in the beginning?

I always wanted to make a film in which every image is infused with eroticism, a totally erotic film. Even Tetsuo I made with that idea in mind. I've been interested in filming the naked body for a long time. Maybe in the case of a pornographic film people imagine that it exploits the image of the female body, but my original intention was to transcend the difference between the male and the female body. The photography of Robert Mapplethorpe was one of my sources of inspirations for this. Making the film fifteen years later, those original ideas have changed. Now the eroticism does arise more from the image of the naked female body after all, which really happened in the course of writing the script.

Mapplethorpe's pictures also express a violent aspect of the human body. Was this what inspired you?

Maybe. That could be part of it.

Do you think there is a relation between eroticism and violence?

They're closely related, both originating from our animal instinct. They are as basic as the need to eat. I think they are fundamental elements for cinema too, but I think a lot of films forget that instinctive aspect or whitewash it. That's why I want it to play a strong part in my own films.

The title of your film is A Snake of June, but of course there are no actual snakes in it. Traditionally the images of the snake and the woman have been connected, like with the figure of Medusa. In the case of your title, is the snake a symbol for the awakening sexuality in the woman?

Yes, in a way. Traditionally the woman is virtuous, but during the rainy season their sexuality is stimulated by the environment. You can sense this oozing feeling inside, which is a bit like the movements of a snake.

The rain is incessant in A Snake of June. The heroine's skin is always covered in either sweat or water, which has a very erotic effect. Does the humidity evoke eroticism for you?

Yes. I always felt that if I were to make an erotic film, I would use the image of skin covered with water drops. When it gets humid and hot in Japan a lot of girls start wearing miniskirts, which provokes some men to start stalking them. There is this kind of erotic atmosphere in the air around that time of the year. Also, I always think of the correlation between the decline of physicality and the modern concrete city. We live in such cities and little by little we lose this physicality that is a basic part of humanity. But if water enters into that correlation, this stimulates the growth of weeds and plants between the concrete, which in turn attract insects, and brings life into this concrete world. New life is born and whether you like it or not, this confronts you with the physicality inside yourself.

I wasn't sure whether this kind of correlation would be a suitable subject to explore in cinema, though. But that feeling changed when I saw Tsai Ming-Liang's film Vive L'Amour. I felt it was about the same kind of subject, the loneliness of people who live in a city. It made me realise that I could adapt my idea into a film.

I have the impression that this film is in a way feminist. Since you said the original idea was more pornographic and violent, do you feel that in the fifteen years it took you to make it, your own point of view towards women has changed?

Yes, I think so. The first half of this film is quite tough on the female character, but I didn't intend to make her miserable. I wanted the heroine to be happy in the end. I don't know why exactly, but when I look at my mother, who is part of a previous generation in which a woman's situation was weaker and mostly aimed at supporting the man, I feel compassion for her and I get this urge to be supportive to women.

The film contains several very typical Tsukamoto elements. Particularly in the scene where the stalker beats up the husband, in which there is this mechanical tentacle protruding from the stalker's body.

When I watched that scene by myself for the first time, I couldn't resist a chuckle. I thought: "Why did I do it again? Why can't I show this in some other way?" (Laughs). But for this film, that was the very first image that came up in my head. A lot of things changed over time, but that image stayed with me. The original idea was sort of avant-garde and drew its inspiration from Georges Bataille's The Story of the Eye. I wanted to keep that aspect in the film, but in that scene I didn't show it so explicitly because I thought maybe it would be a little bit silly. But my films in general are a bit silly (laughs).

Do you think those aspects will change or even disappear from your work from now on? Because you said just before that making this film was like the fulfilment of a life's work, the closing of a chapter.

I think I will change, but when people look at me maybe they won't notice (laughs). Now that I've completed this film, I feel that I probably won't explore this theme of violence anymore in my future films. With the exception of Tetsuo in America.

You're going to make an American version of Tetsuo?

In the beginning it was just a joke, but I already made two Tetsuo films and I don't have the motivation to make a third part in Japan. I want to make Tetsuo in America with a very detailed, American movie feel. I mean that if Tetsuo was a kind of distortion of horror films, then Tetsuo in America will be a distortion of Blade Runner or the Alien series. However, I think The Matrix dealt with the same subjects as Tetsuo, so I have to give it some more thought. It will be a Japanese film, but I would like to shoot it independently in the United States. After Tetsuo in America I think I would like to get closer to nature, and after that maybe I will return again to the subject of the modern metropolis.