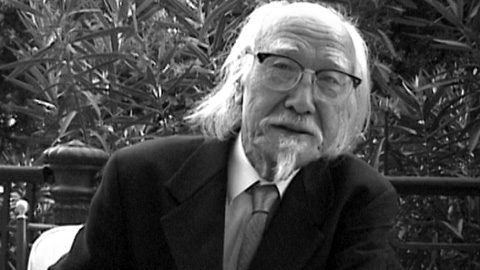

Seijun Suzuki

- Published

- 11 October 2001

by Tom Mes

After three decades of only sporadic filmmaking, Seijun Suzuki's fortunes have finally taken a turn for the better. After two high-profile retrospectives toured Japan in early 2001, the director makes a welcome return to filmmaking with Pistol Opera, in which he revisits his classic Branded To Kill (Koroshi no Rakuin, 1967). The film received its world premiere at the Venice Film Festival, where Midnight Eye caught up with this living legend of Japanese cinema.

People have been saying Pistol Opera is a sequel to Branded to Kill, others say it's a remake. What is it exactly?

The producer, Satoru Ogura, suggested the idea to me of making a sequel to Branded to Kill. So in the beginning I tried to think of it in those terms, with a male character, the same as in Branded to Kill. That didn't work out so well, so I decided to use a female character in the main role. That worked out better. So it started out as a genuine sequel, but it turned into a very different kind of story.

Wasn't it your original intention to have Jo Shishido reprise the lead role?

We did have that idea originally, but somehow it didn't happen. You should ask the producer about that.

The character of Goro Hanada is played by Mikijiro Hira this time. I wanted to keep him as a continuing character. He has survived the last thirty years of being a killer. I originally wanted to make a love story between Hanada and the character played by Makiko Esumi, but I realised it wouldn't work, so I left it out.

The dialogue in the film came across to me as not necessarily narrative, but as sound, rhythms, as a part of the entire composition. Particularly the catchphrase used by Makiko Esumi's character.

The expression "Chu chu takokaina" that she uses is a kind of mimic that we use in Japan, a childish saying that demeans the person you're talking to. But your explanation of the use of the sound as a rhythm rather than as a part of the narrative is correct.

I'd be interested to hear about your approach to casting. How do you choose your lead actors, in particular the actresses of Pistol Opera?

First of all, they must be beautiful. Since this is an action movie, they have to be able to do physical action sequences as well. And for the other people, the little girl's eyes really spoke to me, that's why I chose her. For the character played by Kiki Kirin, the grandmother to Makiko Esumi's character, she has her own aura, her own style, that's why I thought she would be the most suitable person for that role. By casting three generations of women, I wanted to show the audience how the beauty of women changes over the years.

I wondered whether the whole film was shot in Japan, because there are some locations that seem oddly foreign.

All of the scenes were shot in Japan. In my films, time and place are nonsense, so there's no need to film abroad.

What kind of attraction does the action genre, or more specifically the yakuza genre, hold for you?

It's not really the genre I'm interested in, but the character of the yakuza or a killer. They wander between life and death. As a character they are more interesting than normal people. They live very near death, so we can describe how they die, where they die, and when they die. You have a wider range of possibilities than you otherwise would if you were depicting a normal person.

That reminds of what one director once told me about his reason for making gangster films. He said that gangsters' lives are more intense, because their lives are so short. You're able to show the whole range of human emotion in a shorter period of time and in a more extreme way than with regular people.

I think more simple than that. (laughs)

The visuals in your films are often described as, or compared to, pop art. Do you feel any kind of connection with pop art or any other artistic or aesthetic movement?

When I shoot a film, I often look at pictures, drawings and paintings. Not just pop art, but Japanese pictures as well. The reason is because I want to see the form of these pictures, especially in their depiction of women. I don't really understand why it's called pop art in my case. Maybe the result of this way of working turns out to be pop art, but I don't intend to make it that. It just turns out to be like pop art.

To be honest, the choice of colours and such, there isn't much significance to them. Generally, a movie is composed of many elements that make a strong impression on the viewer. I call them tricks. I think colour is one of those tricks.

How did you enjoy working with CGI? Those moments fit in very well, their artificial nature mixes well with your visual approach.

I believe that a movie is a handmade thing, so I don't like new technology so much. If you create a colour on the set, it looks very nice, but if you make it afterwards by computer, then for me it's something fake. But I've experienced for the first time on this film that computer technology can actually be quite useful.

The use of Cinemascope is very typical of your films from the 1960s. So why did you decide to shoot Pistol Opera in the 1.33:1 (or 4:3) ratio? That's hardly done these days anymore.

It was the idea of the director of photography to use the standard size ratio. He felt that in this format every part of the screen would equally dense with colour.

The music by Kazufumi Kodama has a lot of variety and a lot of influences to it, including jazz and ska.

I use music in moments where the audience might become bored. In this situation if the audience hears a lot of variety in the music, rather than one type, maybe it's more fun and not so boring for them. So that's why I did it this way.

Earlier this year, there were two major retrospectives of your work in cinemas in Japan. One of those, the bigger one, was created by Nikkatsu. Does it feel like a vindication of sorts? Because they were the studio that fired you in the 1960s. Do you think: "Now they finally realise that I did make good films"?

(laughs) The best thing for a movie is to have a lot of people come to see it when it's released. But back then my films weren't so successful. Now, thirty years later, a lot of young people come to see my films. So either my films were too early or your generation came too late. Either way, the success is coming too late (laughs).

During the 50s and 60s you made a lot of films, sometimes four a year. The last few decades you have been making a lot fewer films. Would you like to work more than you've done in recent years?

No (laughs). Because I'm old. To be a film director, the first, second, and third priority is to have physical strength. It's not a matter of knowledge or brains.

But a lot of Japanese directors, such as Kinji Fukasaku and Shohei Imamura, who are in their 70s have been making films recently that are very energetic and very dynamic.

It's roujin power! (laughs) Old people's power! It's something that's very happening in Japan recently. So that must be it (laughs).

Your speed of making films in those days, was that because you wanted to, or because of how the industry was structured, the program pictures structure.

I was one of the Nikkatsu contract directors, so it was the company that made me direct films at this pace. Like you said, the program pictures.

Did you enjoy working at this pace?

It was more of a job than getting any kind of enjoyment out of making a film.

Do you enjoy it more now that you make fewer films?

Right now, it's still a struggle to me. Maybe in a few more years I will be able to enjoy making a film. If it becomes more like a hobby, it's also more enjoyable to make a film. But it's very hard to achieve that state, for it to become like a hobby. You need the strength (laughs).

I was told that in the structure of program pictures, films were divided into degrees of importance. The A movie was most important to the studio, so it was closely monitored and controlled. The B movie was a little bit less important to them and the C movie was not important at all. But because nobody cared about him, the C director had the most freedom and he would often make the most interesting film of the three. Which level were your films on and did you benefit from this freedom?

Since I was working for a company, I couldn't deviate too much from the company's course. But because my films were in the B category, I had a wider range than an A director. Even if it went off a little bit, it wouldn't be too much of a problem with them. So in that sense I had a little bit of freedom. More than the A directors.

Clearly you didn't have that much freedom because a few years later you were fired by Nikkatsu. Then you didn't make any films for ten years until Story of Sorrow and Sadness (Hishu Monogatari, 1977). What did you do in those ten years? I heard you were involved in anime at some point. You were also a witness in the obscenity trial of Nagisa Oshima's In the Realm of the Senses, I believe.

I shot commercials, I was involved in animation, the Lupin series. And yes, I was a defence witness for Oshima.

What was your defence argument at the time?

Oh! Well, I hardly remember. (long silence) If you have a book that's prohibited and individual words are crossed out to censor it, which happened in Japan before the war, the book would lose all its meaning. With the film, the same argument applied. That is what happened to In the Realm of the Senses. So I said that if you take out those scenes, cross them out, the film wouldn't make sense. It was exactly like the old system of censorship that we had before the war.

In the last ten years or so you also made a number of acting appearances, in particular in Cold Fever, by Icelandic director Fridrik Thor Fridriksson. How did that come about?

When you become over 60, everything you do is okay with everyone. You can do whatever you want. That's why I started acting. I was invited to be an actor in Cold Fever, so I decided to do it.

Did you enjoy being an actor?

(laughs) It's better than doing nothing at home! It's exciting and also, it gives you money (laughs).

Do you look at actors differently since having acted yourself?

I was mainly acting on TV. I was not a professional actor, more like a semi-pro, so my experiences as an actor are not so important. I'm not a perfect actor, but I also don't surrender completely to the director. I would do what I could, but never go too far from the director's wishes and I would never talk back to him. When I direct, I always make sure that actors don't talk back to me. So I just used the same attitude that I always expect from my own actors.

Cold Fever also starred Masatoshi Nagase, who is in Pistol Opera. Any connection between the two or is it a coincidence?

There's no relation between the two, no.

I believe your next project is going to be a short film that you will be shooting in Paris, starring Sayoko Yamaguchi again. Could you tell how that came about?

The producers invited me to be one of the directors for that project, which is a sort of omnibus film. My sequence is only going to be six minutes long before another director takes over. I believe there are twenty different directors involved.

Why did you accept?

Because my producer forced me to do it! (laughs). Ogura-san kept telling me over and over to accept the offer.