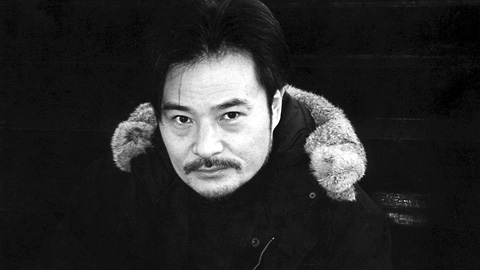

Kiyoshi Kurosawa

- Published

- 20 March 2001

by Tom Mes

When his revisionist serial killer film Cure burst onto the scene in 1998, Kiyoshi Kurosawa was quickly seen as the new hope for fans of fantastic cinema worldwide. As a result of that film's success he is mainly known internationally as a horror film director. On his home ground, the director has above all established himself as the creator of thought-provoking films that walk the fine line between art and entertainment. The following is a composite of two interviews with the director, held in early 2000 and early 2001, both at the International Film Festival Rotterdam.

I'd like to start with your prolific outturn of films. You make about four films a year, I believe.

It's actually more like three films a year. I'm just a very fast filmmaker. I usually take about two to four weeks to shoot a feature. Also, there's not a lot of money for filmmaking in Japan, so if you only make one film a year, it's very difficult to stay alive.

I haven't made them recently, but I used to make a lot of yakuza films. These are shot on film and they have a very limited theatrical release, but in fact they are intended to recoup their cost on video.

What kind of budget do you work with these days?

The yakuza films were more or less around US$ 300,000 to 400,000 a piece. Charisma had twice that, about US$ 800,000. Barren Illusion was very low, about US$ 200,000. My latest film Pulse took a lot of money - well compared to Hollywood movies it's nothing, but still it's twice the budget of Cure.

You're a filmmaker who is very much into a thematic approach to your subject matter. Do you find that makes it easier or harder to get financing and distribution?

In Japan even if you make a strictly entertainment film without any exploration of theme at all, a low budget is around US$ 200.000 or 300,000 and a high is maybe 2 or 3 million. Like I said, it's completely removed from Hollywood levels.

So the budget isn't that important on for instance the casting? On a low budget you can still get Koji Yakusho to star.

Yes, the actors in Japan understand the situation. So even if they also appear in higher budget films, if they like the script they'll appear in the film for very little money.

And I can imagine him being in the film helps finding distribution or financing.

The appearance of someone like Yakusho-san helps to get a little bit more money, but he's not exactly like a Hollywood star. Just that he's in the film is no guarantee that it'll be a hit or that there will be a large audience.

You work with Koji Yakusho again in Séance. What are your reasons for using him so often?

First of all, I think he is a great actor. He can play any type of character. He can be a regular guy, but he can also become a monster, a person of whom you don't know what he's thinking. Secondly, he is the same age as me. So our points of view are alike. We're on the same level as human beings.

There is some interesting casting in Séance where you have Sho Aikawa play a priest. What was your reason for choosing him for this particular role?

(laughs) Aikawa-san and I made a lot of films together, but this bit of casting was very funny. In Japan, people can't think of him as a Shinto priest, as an exorcist. Aikawa-san is a yakuza movie star, so people only think of him as a yakuza. In real life, he is the opposite. He is a total gentleman. So I wanted to show Japanese people that he is not like a yakuza at all.

I, and I think that goes for a lot of people in the West, got to know you through your film Cure, which was very much a genre film. Do you see yourself as a genre filmmaker?

Which genre my film ultimately belongs in is up to the audience to decide when the film is finished, but certainly as a starting point I always start my next project considering which genre I would like to work in. So in that sense I am a genre director.

Actually, I'm often misunderstood. I don't start with a philosophical or thematical approach. Instead I often start with a genre that's relatively easy to understand and then explore how I want to work in that genre. And that's how a theme or an approach develops. The genre is first.

I think that's an approach that very much shines through in Charisma, which starts out as a detective/cop story. Then even when it starts to delve deeper into the themes, there's still occasional flashes of what I would see as genre elements, like the skeleton in the forest.

Yes, it certainly is a detective story, but it's also a sort of American-style Indiana Jones/two-teams-vying-for-a-treasure film. That's how I started it. But instead of a box of treasure I decided to make the treasure a tree that's in a forest. Then you start to imagine "what value does the tree have" and "what is the condition of the forest it's growing in?". Then you start to realise that you're not making an Indiana Jones movie at all, but you're making a much more complex film. That's the process of my filmmaking.

The reason I take this approach to filmmaking is, although film needs a fictional story element, it also is a medium that allows you to record the reality around you. You're filming real forests and real people. I think that film for me is a medium point between a fictional story and reality. You start with the genre, which is fiction, and gradually move towards reality. Somewhere in between you find film.

To put it simply: I would like to make a movie like Indiana Jones, but there aren't any real people like Indiana Jones. That's the premise of my filmmaking.

Interesting that you should mention Indiana Jones, because I thought Koji Yakusho in Charisma looked a lot like Harrison Ford in Blade Runner, with the long brown coat and the bandages.

(smiles) I'll tell mister Yakusho that. Certainly that dirty long coat in Blade Runner is a very memorable film costume. Over the years I've asked my costume department to recreate that kind of a look.

I feel the main character in Charisma is very much a continuation of the main character in Cure. That he's almost intrinsically the same person.

It wasn't intentional, partly because I wrote the script for Charisma ten years before I made Cure. So I didn't intend it as a Cure sequel at all, but then having made Cure with Yakusho-san and then having cast him again in Charisma I guess it sort of naturally developed that way.

In Charisma there are a lot of very strong themes. The message at the end appears to be to accept life and society as they are, where most of the characters either represent very reactionary or very revolutionary forces.

I didn't come to a clear conclusion myself in the film, but I'm certainly happy to have you take that interpretation. It's not far from my own. I would like to say that accepting life as it is, is not a weak or a pressured or a pessimistic thing. I think it's quite the opposite. It's a strong, aggressive, positive stance that can sometimes include elements of violence.

There also appears to be a very strong theme concerning individuality in the film, which is interesting because that same theme is currently also very much present in American films. I also saw it in Kinji Fukasaku's film Crest of Betrayal here at the festival, which is only a few years old.

I'm always interested in how a single human being runs his or her life. I would say that the big difference with the characters in Fukasaku's films, whether they be from Crest of Betrayal or the Battles Without Honour series or whatever, is that in mister Fukasaku's case the role of the group that the individual belongs to is quite significant.

I think that the fundamental difference is that I'm not so interested in the group that surrounds the individual. I'm interested in the values that the individual has come to embrace. For the individual to re-assess those values and understand the way in which those values that he has come to embrace are in fact the forces that have come to oppress him, and that oppression is not something that comes from the outside.

Charisma once again has a very strong atmosphere to it, visually and through the use of sound effects and music. There was a strong parallel to Cure in that many of the sets and surroundings are run down and dilapitated.

Certainly that's true. Partly it's just a matter of my taste. I tend to make my films in and around Tokyo and one of the sad things about Japan, especially around Tokyo, is that as soon as something is a little bit old it is destroyed and recreated into something new. I guess whenever I find some place in ruins or falling apart I know it won't last. I know it will be turned into something new very quickly. Even though the location may or may not have some relation to the theme, I find myself filming there just in order to make a record of this wonderful ruined place.

Something that helps in establishing atmosphere is sound effects. In Cure there was an almost constant droning sound in the background, which I hear in Charisma every now and then and in Barren Illusion as well.

In my films I don't like to use sound to elaborate the story. The story is the story and sound operates on a slightly different plane. As I mentioned, film to me is somewhere in between reality and fiction and I think of sound as defining the world that I've created in that film. Sound is what defines the place that is neither story nor reality, but in between.

Because I think when you're telling the story in visual images you reflect the characters and they can only be what they are. They are two-dimensional. But in a way sound can give you a three-dimensional signal of the world.

Does that go for music as well? Because I thought the music in Charisma was almost the opposite of the rest of the film. It was upbeat and almost happy.

You could say that with the music I take a similar approach, but the music for Charisma was extremely difficult. The direction that I gave my composer was that I wanted him to compose folk music that belonged to no country anywhere in the world, that sounded oldish but actually be new, sound newish but actually be old.

Moving on to Barren Illusion, you worked with a student crew from the Film School of Tokyo on the film. They also contributed to the premise of the story, it being a love story. But also what struck me was that you were working with these very young actors. The only older character in the film is the doctor, who disappears at a certain moment and after that the characters seem to only be getting younger.

Well, except for Shinji Takeda, who plays the main young man, they are all students in the school and the doctor is the school principal. Actually that wasn't so much the way we started out, that we only had to cast from the school, but we had a lot of fun and that's how it ended up.

It's not like there was a role of a doctor in Barren Illusion and then we thought "who would be right for the part?" It was "that principal's really unusual, what can we make him do in the movie?" We didn't take a commercial approach and instead I tried to go back to the feeling of the fun we had making 8 millimeter films when we were students, which is why we had so much fun making it.

What's the significance of the soccer matches and the soccer fans in Barren Illusion?

It doesn't have to be soccer at all, it's the phenomenon of sports fans in general. I'm not particularly a sports fan of any kind, but I see that in the moment when they're all cheering on their team, there's a sense of belonging. Of course the minute the match is over, they go their own ways and have nothing more to do with each other. So I was interested in this sort of fake or extremely temporary sense of belonging and that's what I wanted to convey.

Did education play a part in the style you chose for the film and how you shot? Because you use some very classic camera effects, like the dissolve of the boy who sits in the window sill.

I didn't think of what educational effect a particular shot or a cut would have on my students at all. I did whatever I wanted. The only consideration was to convey to my students that you can make a film any way you want to. What I wanted to communicate to them was: as long as we keep the film to around 90 to 100 minutes, as long as you follow that rule anything else goes, any freedom in making it. That's what defines a film. If the film were 15 minutes long or 10 hours long it wouldn't be here in the Rotterdam Film Festival. I wanted them to know that's the only rule you have to follow. Everything else is up to you.

Those particular shots, the dissolves, reminded me very much of that famous scene in Nosferatu.

I'm very familiar with that famous shot at the end of Nosferatu. There's no direct relationship between Barren Illusion and Nosferatu, but that kind of very simple, fundamental film technique I think can still have a very powerful effect if you use it intelligently.

I think that kind of disappearing, in a non-visual medium it won't work. You can't do it in a novel, it's almost impossible to do on stage. So those kinds of very simple techniques that belong only to film, even though we now have a lot of computer graphics, I like to treasure and value those expressions that can only be accomplished in the film medium.

Even though it's playing here at the Rotterdam Film Festival, Séance was originally made for television. Was it only released on television in Japan?

Yes, it was made specifically for television. Usually when you make this kind of tv drama, it's shown on tv and subsequently released on video and then it's over. But this time it was really different from normal. I made it as a film. I was actually hoping for film festivals to ask me to come show this film and thankfully that was what happened. But this is not the normal situation for a tv drama.

Is making a television movie any different from making a film for the theatres, technically or budget-wise? Or did you have to make any concessions to your way of working or your style?

I think there weren't a lot of differences. I didn't have a big budget and the shooting only took two weeks, so it's the same as with a low budget film. I shot on film, so that's the same too. The only thing was that I couldn't use shocking scenes. It has to be more quiet. There aren't a lot of people dying, because that's not allowed.

How do you see the chances of your latest film Pulse, which will be coming out in February 2001. This is a big studio project. Do you think this will be the last chance you get to make this kind of film as a studio project?

When Ring and all these horror films became such a hit in Japan and the horror boom started, I took the chance of making this film. I'm not sure of course if it's going to be a success. If it's not, it might mean the end for this type of film, because I think audiences are getting a little bit tired of them.