Kiyoshi Kurosawa

- Published

- 20 August 2013

by Tom Mes

Midnight Eye has been closely following the career of Kiyoshi Kurosawa since the site’s inception. The first interview we ever published was in fact with Kurosawa, held in 2000 and 2001 at the International Film Festival Rotterdam, and this was followed by many other encounters over the years: interviews, set visits, festival screenings.

One of the characteristics that make Kurosawa such a fascinating figure, aside from the consistently high quality and challenging nature of his films, is that his career has evolved along with every major development in Japanese film of the past 35 years: like many other now-established directors he had his breakthrough thanks to an award at the PIA Film Festival in the late 1970s, found mentors in the epoch-making shapes of Shinji Somai, Kazuhiko Hasegawa and Juzo Itami, and debuted professionally in pink film. During the 1990s, he found refuge in TV and straight-to-video production before emerging as one of the “new new wave” of Japanese filmmakers discovered by western film festivals with Cure.

In this brand new and exclusive interview, we talk with Kurosawa about his rarely covered but highly influential work in V-cinema, the arena of straight-to-video filmmaking.

Serpent's Path

Your first straight-to-video production was in 1994, if I’m not mistaken. How did you originally receive the offer?

My first V-cinema work was called Yakuza Taxi. The offer came from a production company called Twins, who I still work with today. The offer just arrived one day, out of the blue. One of the producers asked me if I would be interested in directing a V-cinema production. I later discovered that this producer, who is younger than me, was a big fan of my earlier films and had long wanted to work with me. When he was promoted to producer, where he could oversee an entire project by himself, he really wanted to work with me. So he came to me with the offer and said "I know this is just V-cinema, but would you be interested?"

What was your situation at the time? You seem to have been mostly working in TV at that point.

At the time I was working in TV, yes. I was not able to shoot a feature film. Not that I was dissatisfied at that moment, I was quite happy to work on those TV projects. I was young at the time, and I felt that many of the films that were being made in Japan weren’t very interesting. I had the desire to shoot an action film, which would have been very difficult to do within the context of TV production, so I thought that in V-cinema I might get the opportunity to do an action film. So I immediately agreed to the offer from Twins. I did make a few horror-themed projects for TV, but I’d never had the chance to do action. Even now, in feature films, it’s very difficult to do an action film as a project, to get it funded and off the ground. So my desire to work in the action genre was the reason why I accepted the offer.

What I remember clearly is how KSS, the parent company to Twins, had very different views of the project from what I wanted to do. Twins understood my intentions, but KSS wanted a more straight yakuza film. I wanted it to be an action film featuring yakuza, more like an American film, with straightforward action, but with yakuza characters as a kind of setting. KSS were very adamant, so we had some very heated discussions about this. I said, "What do you mean by ‘yakuza film’? I’ve never even met a yakuza in my life. Who are they? What do they do? What is their world like?" They explained to me that it is a world of jingi, people who live by a code of honor. So I replied that I was of the post-Battles Without Honor generation and that I thought this code is very superficial and there are no people that actually swear and live by it. So I couldn’t make a film like that. Yes, there was much contention.

That said, it was a V-cinema production and Twins was in a position to mediate. So they said to KSS that the film in any case had yakuza characters and there was no need to obsess over this idea of jingi. They relented in the end, so I was allowed to elaborate the story with that understanding. The original idea about yakuza having to operate a taxi company came from KSS, so the basis of it was comedy to begin with. And it did end up more like a comedy than the kind of action film with car chases, gun fights and people dying that I wanted to do. I didn’t get to shoot those kinds of scenes on that project. It really had nothing to do with jingi either.

But the film was very well received and it led to me receiving many other offers to work in the field of V-cinema. Funnily enough, after that, even if there were yakuza characters in the film, KSS would say, "If Kurosawa is directing the film, never mind the jingi."

What was your own impression of V-cinema at the time?

At the time I was making these straight-to-video productions, there were arguments about whether V-cinema was film or not. Some argued that if it had a theatrical release, it was a film. Or if it were distributed outside the country, then it was a film, even though those films were regarded as V-cinema domestically. There were all sorts of viewpoints and there was much debate about this. I myself am still ambivalent about this question of whether V-cinema is film or not.

When I think back to that time, nobody thought that we were making films. But there is a similarity in terms of conception with Roman Porno and pink films, where the budget is very low but there is very much this air of everybody letting the director do what he wants to do and to realize his ideas. I believe that’s the tradition of the studios of the 1950s and the 1960s, and that mood was still very much prevalent in V-cinema. Even if there were arguments with producers, ultimately the idea was to support the director. That resulted in a very comfortable and worthwhile environment for the filmmaker. Especially for a director, to be valued and for that supportive environment to exist, is a special thing.

What was it that KSS and Twins brought you at the time? What status was the project in? Was there just a title? Was there a screenplay? Was there a cast already in place?

I believe KSS had a writer on staff who came up with an original story and also wrote a script based on it. When they brought it to me, they said, "It’s not very good, so please go ahead if you wish to rewrite it to your own liking." In terms of casting, it was all KSS and Twins who made those decisions.

Was this a representative situation for the V-cinema productions you worked on?

With most of the projects I worked on, the producers decided the casting. I used to tell them to choose whomever they wanted. In terms of content, since most of my movies starred Sho Aikawa, producers would approach me and say, "Let’s have Sho Aikawa do a comedy next, or maybe a hardboiled revenge story where he kills all sorts of people." They gave me that sort of very broad concept. I would say, "Yes, I’ll think about it" and start writing the story from there on.

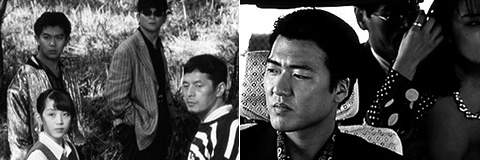

left: Suit Yourself or Shoot Yourself, right: Yakuza Taxi

Your second V-cinema production that same year was Jan – Otokotachi no Gekijo, a film about speed cycling.

It was based on a manga series about professional cycling. There had been a previous film based on it, so my film was essentially Part 2. It had nothing to do with yakuza, obviously. There are people who call it my masterpiece (laughs). Looking at my filmography, it is the only ‘sports action’ film that I’ve made. It’s really interesting that V-cinema also included those kinds of stories as well.

Even though the budget was very low, given the subject I believe it was a film that should have been aimed at a theatrical release to begin with. At the time V-cinema had the ability to tell these kinds of stories for a straight-to-video release instead of having theatres as an ultimate goal. Of course, it was less of a gamble to do it straight to video. But it’s an interesting film, looking back: it wasn’t a yakuza film, it didn’t star Sho Aikawa, so it’s interesting that I actually made this film.

How do you look back on the films themselves, the end products?

One of the things I’m still surprised about was that I managed to shoot those two films in the same year. They are both around 90 minutes in length and I basically wrote the scripts as well, so it was a great source of joy and surprise for me that I managed to do that in one year.

Do you mean technically or creatively?

It was more the idea of not going over budget, to be able to finish the film within the time frame I was given, and at the same time to make it a good enough film. I admit I had a certain fear when I embarked on the job, but the figures were never in the red and I was able to deliver two films I was happy with and that other people involved were satisfied with. That was a great source of joy, to know that I could be not just an auteur type filmmaker but also a craftsman in this trade. That I could make something I was happy with and that didn’t put anyone else in a difficult situation.

You’ve likened V-cinema to program pictures in the past. Were those a model for you when you began making V-cinema films?

It’s not that I was consciously thinking that I was making program pictures at the time, but as a result I understood that what I was doing was similar to the program picture. The terms you offered are to make a film within a certain budget and schedule, with a certain star attached and a story outline. If you stick to that, then as a director you can do whatever you want, with the safe knowledge that to a certain extent you are covered, because the numbers have already been calculated in advance on the basis of the star and the story. In an interesting way that brings you the security to do what you want. In my opinion that is what defines a program picture. The term ‘program picture’ I associate very much with low budget science fiction, crime and horror films made in the 1950s and the 1960s in the USA, like Roger Corman’s studio, or Hammer Films in the UK. Even in the 1970s there were still a lot of program pictures. It was exciting and a great feeling to be able to work in V-cinema and realize that there was a connection with those earlier films.

That becomes even more evident with the Suit Yourself or Shoot Yourself series, since you made six episodes in the space of two years, with very similar stories and the same lead actors as recurring characters.

It was produced by the same company, KSS. They had recognized that I was capable of directing V-cinema productions, which is why they asked me to work with Sho Aikawa, who was the biggest star in V-cinema at the time. It’s true that there are six episodes, but I shot two back-to-back each time, so I went into production three times for two films or stories each. It’s true that I had to develop six individual stories for these and looking back, I still can’t believe how I was able to accomplish that. But this is the thing with V-cinema: once the film is in the can, your work as a director is done. That is very different from feature films, where you have to promote the film and you sometimes have to do stage appearances in theaters. Even when it’s a small, independent film, as a filmmaker you worry about the critical reception, how it does at the box office, etc. As you know, Kinema Junpo has an annual ranking, for which all the critics write in their top 10. Filmmakers try not to place too much importance on this, but it’s true that they are a little concerned about it. These things don’t happen with V-cinema: when you finish a film, it’s done. That’s probably one of the biggest reasons why I was able to do six films in such a short period of time. Unexpectedly, I came to like this system a lot. I’m not the type to obsess over my work and I usually after I’ve finished a project want to move onto the next one.

Suit Yourself or Shoot Yourself

Your way of shooting, your approach to film projects - working fast, usually doing only one take, filming multiple projects in one year - were these shaped by your years in V-cinema?

I would say so, yes. Shooting that many films in that short amount of time greatly disciplined me as a filmmaker. I must say I was a fast shooter to begin with. Even when I was making 8mm films, I was fast. But I did learn the technicality of maintaining a certain level of quality, even if you do have a very fast-moving production. In addition to that, having to deliver a script, so many scripts, in such a short amount of time, was definitely great training for me. Even if there was more to be desired, you had to turn something in within two weeks. That was the first time in my life where I had to write something so fast.

On that series you did work with other scriptwriters too, didn’t you?

That’s true. When I do two films back-to-back, I will write one script and ask another writer to write the other one at the same time. I started doing this on Suit Yourself or Shoot Yourself. But even if there was another writer, I would normally rewrite their material, which is why we were credited as co-writers. So I did actually work on all the scripts.

Later, with the Revenge series, I worked with Hiroshi Takahashi. Although we were friends, we had very different ideas about the writing, so I decided to let him write what he wanted, which is why he is solely credited for that project. But this was great training too, working with other writers, discussing the story and trying to figure out what to do.

You once explained to me that making a film is part fiction and part reality. Shooting six films essentially back-to-back, your style of recording reality must develop very quickly.

Yes, to some extent, but I don’t think that that style is absolute. Even now, if I feel that I have my own style of directing, that style shouldn’t be absolute, so I look for ways to break it. Even today I continue to test and try new things.

My encounter with Sho Aikawa was very significant. At the time he was a brand unto himself: it wasn’t about the story or the character, it was about him. He was a genre in himself; ‘Sho Aikawa-starring V-cinema’ was already a genre. That gave me an incredible freedom, because that was the fundamental element of the fiction I was creating. Aikawa himself turned out to be incredibly flexible and multifaceted. We would shoot scenes without written dialogue and have him improvise. I was able to experiment and try out many things with Aikawa and still remain real, because that was the width he had as a performer. And yet his brand remained intact, no matter what I threw at him.

The impression I have of a certain development in your style is that there is a change around the time of Suit Yourself or Shoot Yourself. Before that, you seemed to employ a style based on American filmmaking, which from there on in seemed to change. Could this be the result of that shooting style you just discussed?

Yes, on Yakuza Taxi and Jan I consciously wanted to stay true to the style of American filmmakers. This was also true when I started on the Suit Yourself series, but as I just explained, Aikawa’s appeal overpowered my fondness for the American style. When you’re making six films like that, one after another, I wanted to try some different things as well. I’m not sure at which point in the series exactly it started to shift, but it’s true that the last film, in 1996, was completely different in terms of where I was heading.

And there is another element. In the 1990s, there were films that were not quite art house cinema but which were nevertheless acclaimed overseas. Takeshi Kitano is an example of this, albeit on a different level, but also Shinji Aoyama, who used to be my assistant, and Takashi Miike, who I didn’t know at the time. These people were having their films shown at festivals abroad and were well received by critics. These films were different from American films; they had constructed their own individual style as auteurs, yet they were going abroad and being recognized. To me, it was a revelation that this could happen. It wasn’t just about the domestic box office or getting a high ranking on the Kinema Junpo list, there was a different value attached to another way of seeing Japanese films that became prominent. It was incredible to me at the time to see these films that were very close to V-cinema being invited and shown and seen and received by foreign critics and audiences. This definitely had an impact on me and was on my mind at the time. Maybe that’s one of the reasons why I shifted my style away from the American influence.

You know, I spoke about my love of American cinema, but those are not the only films I enjoyed and loved. There were other filmmakers, like Theo Angelopoulos, Abbas Kiarostami and Edward Yang – non-American filmmakers, auteurs – I liked a lot. I wanted to incorporate, forcibly almost, their touch and influence into the Suit Yourself series toward the end. It was a kind of experiment, but it’s also a testament to how generous Aikawa was, that he gave me the space to experiment.

With you finding out that other Japanese filmmakers working in their own styles were getting shown abroad, was this a goal you consciously started working toward?

I definitely felt that I wanted the same to happen to my own films. I remember distinctly when we were shooting The Revenge, Shinji Aoyama, who had been my assistant director on the first couple of films in the Suit Yourself series, had just made his film Helpless. I remember being on the beach and asking someone on the crew what Aoyama was up to, and they told me, "Oh, he’s actually at a film festival somewhere in Europe." I remember being frustrated and envious, realizing that he had moved so far ahead of me. I had never been to Europe and felt that I wanted to travel there with my own film at least once in my lifetime. Those feelings I incorporated into my film The Revenge.

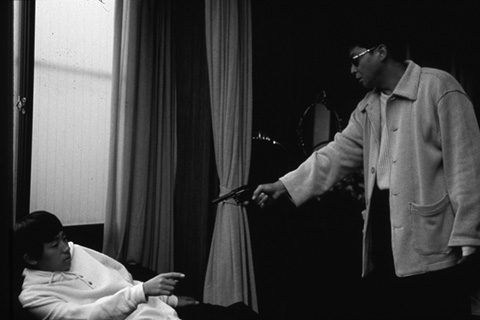

Eyes of the Spider

But instead it happened with Cure.

That’s true. I hadn’t really imagined that that film would make it overseas while I was making it. It was the first film that was invited to an ‘international film festival’, but it was the Tokyo International Film Festival, so I was excited but also disappointed in a way because it was still in Japan. After that, the film was shown in France and Rotterdam as well, so I was incredibly happy with that development.

It’s interesting that Cure was the first of my films to travel overseas. I’m not sure the same could have happened with a V-cinema work, because the appeal of Sho Aikawa may not be immediately obvious to foreign spectators. Yakuza films are not about real yakuza, but about a traditional type of cinematic yakuza character. You have to know that as a basis to appreciate Aikawa. Whereas a story like Cure, with a detective who gets involved with a serial killer, is probably easier for foreigners to wrap their heads around. Though I must say, since J-horror is such a typically Japanese thing, I was really surprised to see it struck a chord with overseas audiences.

But Cure was also made with larger means and intended for theatrical release.

Yes, it had a bigger budget and was meant for theatrical release, but the budget wasn’t that extravagant. In terms of atmosphere, the production wasn’t that different from what I was used to: it was produced by Twins, the same company that produced my V-cinema works, the crew consisted mostly of the same people, and although the cast was different I wasn’t aiming to make anything completely different from my V-cinema films. I mean, Ren Osugi is in all of them (laughs). I was able to work on a slightly higher level in terms of budget, but that was the only difference.

After Cure you made Serpent’s Path and Eyes of the Spider, which were made back-to-back according to a V-cinema model, and also had a video release title that bound them together as a pair.

Initially these two films were intended as parts 3 and 4 in the Revenge series. Cure came between parts 2 and 3, if you will. So these were the last two V-cinema films I made. It was actually before Cure had been released or seen at all, so my approach was the same as on the previous V-cinema productions, I just had a great time. I mentioned how, with Yakuza Taxi, I originally wanted to do an action film, but that film, as well as the Suit Yourself series, ended up more like comedies. They didn’t feature action scenes with people dying left and right, which I got to do finally with Serpent’s Path and Eyes of the Spider. They fulfilled that long-held desire of mine.

Talking to you about my experiences at the time, I now finally realize that with my work of that time - Serpent’s Path and Eyes of the Spider, and Cure in a way as well – I was finally able to feel satisfied about having done an action film the way I wanted to. But when you look at the films, the expression of action, which I originally felt was strongly influenced by American films, came out very different. Not that I intended to do so, but maybe it was born from my being able to form a very individual and idiosyncratic cinematic expression, which was cultivated somehow by my experiences making V-cinema. I realize that people don’t actually see those scenes in Serpent’s Path and Eyes of the Spider as action scenes, but even now I think they’re great action sequences.

It’s interesting because I only realize it now while talking to you: by working in V-cinema I was able to try out what I initially wanted to do, what I perceived as action cinema, and through that, I was able to find my own expression.