Katsuya Tomita & Toranosuke Aizawa

- Published

- 16 February 2013

by Jasper Sharp

Many people wouldn’t perhaps associate Japan with much in the way of cultural or ethnic diversity. If they do, it is most likely to be with reference to immigrants from neighbouring Asian countries, or the sizeable population of American and European expats working as English of other foreign-language teachers in the larger cities such as Tokyo. They most likely wouldn’t think of Latin Americans.

But Japan also has a sizeable Brazilian community, mainly living in industrial, manufacturing-based cities such as Hamamatsu, the result of a legacy that began in the first decades of the twentieth century when a large exodus of Japanese left for Brazil in search of a new life. Without the means to return to their home country, many settled there, only for successive generations to return in the economic boom years of the 1980s to fill in the labour shortage. Considered foreign nationals, the population of these new migrant communities reached 300,000 at its peak, although it is now in decline.

This history of a people whose national identity is split between two separate continents has gone largely unreflected in Japan’s cinema, although there have been some noteworthy films on the Brazilian side - notably Gaijin, a Brazilian Odyssey (Gaijin - Os Caminhos da Liberdade, 1980), a drama focussing on the early influx of Japanese to Brazil, and its companion piece, Gaijin 2: Love Me As I Am (Gaijin - Ama-me Como Sou, 2005), both directed by Tizuka Yamasaki, the Brazilian-born daughter of such immigrants.

Nevertheless, the Brazilian presence became something of a hot topic in Japan in 2012, with Kimihiro Tsumura and Mayu Nakamura’s documentary Lonely Swallows: Living as Children of Migrant Workers (Kodoku na Tsubame-tachi: Dekasegi no Kodomo ni Umarete, 2011), which focused on a number of young characters forced to make a decision between two very different worlds following the decline in Japan's manufacturing base in 2008; in fictional form, in Shohei Shiozaki’s magical realist fable Goldfish Go Home (Sanba da Kingyo, 2012), featuring a young Brazilian immigrant boy whose life is transformed after discovering a magical blue goldfish; and last but by no means least, Katsuya Tomita’s ambitious jishu eiga epic, Saudade.

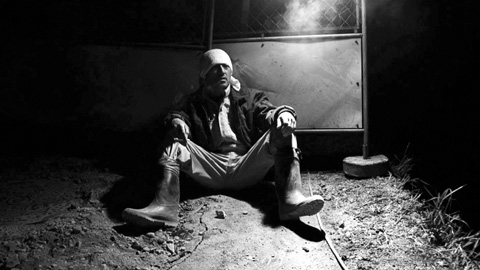

In Saudade, the Japanese-Brazilians are more a presence than active protagonists, a small component of a multi-threaded drama in which they are not the only ones looking beyond their immediate suffocating environment to foreign shores, a glorious past or an ever-elusive utopic future. As its director points out, the film is more a portrait of a small city, in this instance Kofu (where the director himself grew up), as it is about its individual denizens of down-on-their-luck construction workers, disenfranchised hip-hopping youths, small-time hoods and Asian bar hostesses.

Following on from his previous Off Highway 20 (Gokudo 20 Gosen, 2007), a lightly comic Shane Meadows-esque portrait of a group of hapless young men living in the suburbs of this very same city, Saudade sees the director broadening his canvas to present a vision of Japan that will be as unfamiliar to foreign viewers as it will be instantly recognisable to the inhabitants of many similarly-sized conurbations across the country.

Tomita and his scriptwriting partner Toranosuke Aizawa came over to London in September 2012 to present their film as part of the Melting Pot Japan strand at Zipangu Fest, in which Lonely Swallows also screened. The following conversation is a transcription of the onstage interview following the film, conducted by Jasper Sharp with Bethan Jones interpreting.

JS: Thanks for coming over to London and showing us a side of Japan which we are not so familiar with. I think what I like most about Saudade is that there are a lot of aspects that could be just as applicable over here too, regarding the declining economic situation in small towns and immigrant communities that feel trapped by these circumstances. What was it that prompted you to tell this story?

KT: After we made our two previous films, which were both set in Yamanashi prefecture, we were wondering what to do next, but we thought we’d like to try and do something in which the town was the main character. So that’s when I started the research.

TA: Both of our previous films were shot in the same area in Yamanashi prefecture, and in the two or three years it took us to make each of these films, the town and in fact the entire area totally changed. We really wanted to depict that change in the next film we made.

JS: I know, Tomita-san, that you were born in this town. Were both of you born there? And leading from this, obviously the main filmmaking scene in Japan is based in Tokyo, so I wonder if you are based there or if you feel very much like outsiders, and how this outsider status influences your work.

KT: Only I was born there. We both live in Tokyo now, but yes, in answer to your question, we definitely feel like outsiders in the film industry! We’ve never treated filmmaking like a business, and for this very reason, there are certain things we can do in our films. But on the flipside, it is hard to raise money and for that reason we’ve had to make some sacrifices. Japan has a long history of film, and in the olden days there was a lot of money floating around the industry and you could more or less make the type of movie you wanted. Recently however, the industry has been struggling a lot, and you have to make the kind of thing the audience wants to see. That’s not really the type of content we were happy with. So we made Saudade using our own savings, donations and loans, which we are still gradually paying back.

TA: I’d just like to add that in Japan, you hardly ever see films or television programmes that deal with the fact that there are so many immigrants. They don’t touch upon the subject at all, and in fact I think they deliberately avoid it.

Saudade

JS: Tell me more about the title.

TA: It's a Portuguese word that we learned from the Brazilian-Japanese immigrants, and they said that it is hard to translate into Japanese, but it includes thoughts of the past, of your home and your country, but also hopes for the future. There’s also a play on words too - the apartment complex where they all live is called Sanno Danchi.

KT: The Sanno Danchi estate is a real-life estate where these Brazilian immigrants live, and when they say the name with their accents, it sounds a lot like ‘Saudade’. So when we were developing the script, we originally misheard what they said, and thought it we’d put it in the film as a joke.

JS: So as you say, a film like this is obviously very difficult to get made, but how difficult was it to get shown? It seems very much to me that the industry has completely split into two over the past 5-10 years, where the major studios are just making vapid and glossy TV tie-ins like Boys Over Flowers or Umizaru, whereas all the interesting stuff is happening at the low- to zero-budget end. But the major studios also operate most of the cinemas as well…

KT: Yes, we do have the big cinema complexes where they screen all the Hollywood films and Japanese commercial entertainment films, but we also have what we call the "mini-theatres", which are quite deeply rooted in Japanese cinema culture - small, single-screen venues with about 50-100 seats. These are the kind of places where Saudade is being shown.

JS: Has the film’s long running time been a problem?

KT: The mini-theatres do struggle to get their programmes together, so you’re right, they aren’t too keen on longer films. But we’ve been fortunate, because this film was really quite a hit, so it has gone on to play at quite a few venues across the country.

JS: The focus of this year’s Zipangu Fest was centred around such questions as "What is film?", "What is cinema?" and are they essentially the same thing? Is there a need for film now we can shoot and project everything digitally? This rather circularly turns to our other theme of the festival, which is "nostalgia", or indeed, Saudade… I’m quite interested where you stand on the film/digital debate, because your first film, Above the Cloud (Kumo no Ue, 2003), was shot in the amateur 8mm gauge filmmaking format, long after cheap digital cameras became the norm for indie filmmakers, but it was converted to digital tape in order to be screened. Off Highway 20 was shot in 16mm, then converted to digital. Meanwhile, Saudade was filmed on HD video but transferred to 35mm for projection at a time when digital projection is becoming the new standard.

KT: Like I said, there’s not a lot of money in the Japanese film industry at the moment, and audience numbers are falling, so this is why a lot of people are going into independent jishu seisaku eiga (self-produced film) production. So for all of our three films, we put them together while we were working, on weekends or on holidays. I worked as a truck driver, for example.

But we wanted to use film as much as possible, because of this love we have of the medium as movie makers. As we’ve been creating our films, digital cameras have become even more widely available, and it is possible to film things more easily and even more cheaply than usual. But the movies we’d grown up with, which we were used to and which we loved, were all shot on film. Just because the general image of film changed with the increased use of digital cameras, it didn’t mean that we could suddenly update these mental images we had in our heads of what movies should look like. We felt kind of uncomfortable using digital, which is why we stuck with film.

JS: At present a lot of venues are ripping out their old equipment and refurbishing with digital projectors. We might feasibly get to a stage in a few years where the number of venues and opportunities to screen 35mm will be severely diminished, and, on a purely practical level, there will be far fewer skilled projectionists who even know how to operate a 35mm projector. I don’t know if that’s going to be the case in Japan, but what do you think of the accusations that adhering to film because you just like the look of it, and using the format purely for aesthetic reasons has no logic, and is basically just fetishistic.

KT: I’m 40 years old, so maybe I’m part of that last generation that has that film fetish. When I started studying film, a director I studied under said to me "Tomita, film has only got a hundred years of history behind it. It is far too soon to set these kinds of rules. It is too soon to say film must be film, or films must be an hour and a half long." Still, that hundred years of history are the films I’ve grown up watching, and the ones that I’m used to, so maybe we’re that generation who have come to that turning point and has to choose where the future of film lies. And as I said, it’s not easy to completely change your ideas of what film is from what you’re used to. So we have to keep asking ourselves this question of "What is film?" Maybe I’m just part of that last generation who feels that resistance and still has this love for celluloid.

Saudade

JS: I guess we’re roughly the same age, and though I’m not a filmmaker, I did actually make a short film many years ago on 16mm, and from a sheer practical stance, you get a totally different philosophy towards the medium when you are physically manipulating it, cutting up strips of celluloid and sticking them back together again, cutting up an actual soundtrack and sticking it onto the film, then putting all your offcuts into a bin, and discovering you’ve accidently thrown away a vital bit, so you then have to scrabble around trying to find it… It gives you such a difference approach intellectually, I think, because the film stock is actually a physical medium that itself costs money, so you have to think a lot about what you shoot so you’re not wasting it.

KT: Exactly! It’s just as you say, and that’s one of the biggest differences between film and digital, I feel. Because film is a physical thing, as you say, and you have to cut it, and stick it all back together, and if you lose a piece, you have to find it. And that’s something that comes across when I’m watching a digital film or a celluloid film. A digital film for me looks a lot smoother. You don’t have those moments where you feel that the creator has actively made a certain editing decision or has taken that step to cut it in a certain place. It feels a bit watered down, if you like.

I think, as we’ve said, we’re at that turning point from analogue to digital, and maybe my generation is the last that can bring those properties and characteristics that films has into digital cinema, that power that film has to draw people into it. Maybe we’re the last ones who’ve learned from the generations before us about that and who can carry that forward.

But I think digital will keep progressing in its own direction. Just the other day, Fuji Film announced they weren’t going to manufacture film any more. But ultimately, it's still the same basic idea that you’re using a camera to shoot something. It will give rise to new ways of doing things, I think.

JS: Which of the characters in this big multi-threaded drama do you both personally identify with?

KT: I’ve known the two actors playing the construction workers Seiji and Bin (the one who has just come back from Thailand) since primary school, so these are the characters I feel most attached to. But as I said, in this film, it's the town that is really the character, and in this town you’ve got all generations, sexes and ethnic groups, so we really wanted to depict all this, particularly the different generations.

TA: I’m the same age as those two actors as well, and then you’ve got the hip-hop guy, who’s slightly younger.

Saudade

Audience question: Are there any plans to show the film in Brazil, and also, how did the Brazilian-Japanese community react to your film?

KT: We finished making the film actually in 2010, which was around the time when the Japanese economy started going rapidly downhill, after the Lehman Brothers shock in 2008. Because of that, a lot of the Brazilian people in the town had left to go back to Brazil. So even a lot of the Brazilians who appeared in the film never got a chance to see it. We’d love to be able to screen it in Brazil, but we’ve not managed to find that opportunity yet.

AQ: Did you have any main objective or message you wanted to impart with the film, or was the objective just to portray the town?

TA: It is an attempt to depict real small-town life in Japan, but if it was just that, we might just as well have made a documentary. So there is a message, and from my point of view it is that everyone has different views, everyone makes mistakes, but everyone has a right to live their lives, and I wanted to make audiences think about what it is that suppresses that for people.

Saudade

AQ: A lot of the actors were non-professionals, so I wanted to know to what extent that influenced the scriptwriting process and the making of the film. Did you write the characters around the actors, or did you have something more tightly scripted and then cast the characters in the various roles? Basically, how much was improvised?

KT: There was some improvisation, but actually very little. We spent a year on research, and spending time with people in the town, writing down the experiences we had and turning this into a script. Then we essentially just gave the script back to them so they could act out the things they’d already done and the conversations they’d had.

We were working in our day jobs while we were making this film, and so were all the actors who appeared in it, so we could only really shoot on weekends and during holidays. Over the year and a half that it took us to film, we spent a lot of time with these people, and the more time we spent with them, the more we’d come up with new scenes and new ideas that we would then write into the script. This was the nature of the improvisation that happened. In this way, we managed to come up with about 40 new scenes that weren’t in the original script.

JS: This film came out this year, in 2012, and so did the documentary about Japanese-Brazilian immigrants, Lonely Swallows. Why do you think there’s this interest in this subject in Japan?

TA: Yes, there have been a few other films, such as, as you mention, Lonely Swallows, and also another documentary by a Brazilian-Japanese director. I think it is just because we have a lot of Brazilian immigrants in Japan and we have a long history going back about 100 years of people going back and forth between the two countries.

AQ: Could you talk more about the hip-hop group in the film, Army Village?

KT: They’re a real group, but we changed their name for the film. They’re actually called stillichimiya. Ichimiya is the name of the area they come from. We really wanted to use an existing group in the film to give it a unique flavour we wouldn’t otherwise have if we just got the actors to do it. This was something we felt was important. In real life, they’re not as right-wing as they are in the film. They’re actually quite liberal!

I’d seen this group because Ichimiya is in Yamanashi prefecture, where I’m from, and they represent the town and the area where they are from, and there’s a lot of that in hip-hop. What I think is very dangerous though, is when they start to think they are representing the country as a whole, which is another thing we were keen to show in the film.

Saudade

AQ: At one point you see Takeru, the main young hip-hop character in the film, talking with the boss of the local yakuza group. Can you tell us a bit more about this scene?

KT: Of course, we’re not suggesting that all hip-hoppers are going to go on and join the yakuza. Actually, as we said, most of the people in the film were playing themselves, and these yakuza characters were played by real-life gangsters from the town. Anyway, because it's a small provincial town, these sorts of people, young local guys like the Army Village and the small local gangsters, are often connected in certain ways.

They’re not actually yakuza though. It is a bit hard to explain, but these guys in the suits were actually representing another group which is similar to the yakuza in some ways, although not quite. This is the right-wing group called Seiji Kesha Kokuyukai. These are technically a political group, but people in Japan actually see them as being on a par with the yakuza. They’re the ones that drive around in the black trucks called gaisensha, which go around the streets playing military songs and shouting slogans and saying what a bunch of lazy good-for-nothings young people in Japan are today. So that’s why they are saying to him in the film, "When are you going to grow up and join us?" The people acting the part of these right-wingers aren’t actually members of the right-wing group, but they were members of the local yakuza.

JS: In closing, are we going to see any of these characters again, and what are your plans for the future?

KT: I think several of them may well appear in our next film…