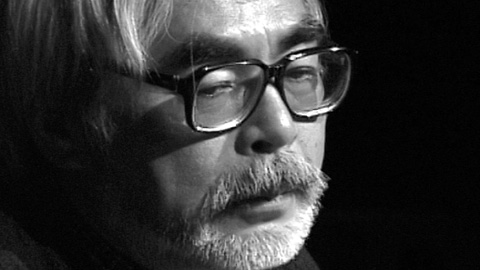

Hayao Miyazaki

- Published

- 7 January 2002

by Tom Mes

There is little doubt about Hayao Miyazaki's status as Japan's premiere animator. After such devastating successes as Porco Rosso and Princess Mononoke, not even the lure of early retirement could keep the most famous founding father of Studio Ghibli from delivering what would become the most successful film of all time in Japan: Spirited Away (Sen to Chihiro no Kamikakushi).

The following interview below is a report of the debate / press conference Miyazaki gave in Paris in late December 2001, on the occasion of Spirited Away's first European screening at the animation festival Nouvelles images du Japon (during which the French government bestowed on him the title of 'Officier des Arts et des Lettres'). It contains questions from various people, including my own.

Is it true that your films are all made without a script?

That's true. I don't have the story finished and ready when we start work on a film. I usually don't have the time. So the story develops when I start drawing storyboards. The production starts very soon thereafter, while the storyboards are still developing. We never know where the story will go but we just keeping working on the film as it develops. It's a dangerous way to make an animation film and I would like it to be different, but unfortunately, that's the way I work and everyone else is kind of forced to subject themselves to it.

But for that to work I can imagine it would be essential to have a lot of empathy with your characters.

What matters most is not my empathy with the characters, but the intended length of the film. How long should we make the film? Should it be two hours long or three? That's the big problem. I often argue about this with my producer and he usually asks me if I would like to extend the production schedule by an extra year. In fact, he has no intention of giving me an extra year, but he just says it to scare me and make me return to work. I really don't want to be a slave to my work by working a year longer than it already takes, so after he says this I usually return to work with more focus and at a much faster pace. Another principle I adhere to when directing, is that I make good use of everything my staff creates. Even if they make foregrounds that don't quite fit with my backgrounds, I never waste it and try to find the best use for it.

So once a character has been created, it's never dropped from the story and always ends up in the final film?

The characters are born from repetition, from repeatedly thinking about them. I have their outline in my head. I become the character and as the character I visit the locations of the story many, many times. Only after that I start drawing the character, but again I do it many, many times, over and over. And I only finish just before the deadline.

With that very personal connection you have with your characters, how do you explain that the main characters in most of your films are young girls?

That would be far too complicated and lengthy an answer to state here, so I'll just suffice by saying that it's because I love women very much (laughs).

Spirited Away's lead character Chihiro seems to be a different type of heroine than the female leads in your previous films. She is less obviously heroic, and we don't get to know much about her motivation or background.

I haven't chosen to just make the character of Chihiro likes this, it's because there are many young girls in Japan right now who are like that. They are more and more insensitive to the efforts that their parents are making to keep them happy. There's a scene in which Chihiro doesn't react when her father calls her name. It's only after the second time he calls that she replies. Many of my staff told me to make it three times instead of two, because that's what many girls are like these days. They don't immediately react to the call of the parents. What made me decide to make this film was the realisation that there are no films made for that age group of ten-year old girls. It was through observing the daughter of a friend that I realised there were no films out there for her, no films that directly spoke to her. Certainly, girls like her see films that contain characters their age, but they can't identify with them, because they are imaginary characters that don't resemble them at all.

With Spirited Away I wanted to say to them "don't worry, it will be all right in the end, there will be something for you", not just in cinema, but also in everyday life. For that it was necessary to have a heroine who was an ordinary girl, not someone who could fly or do something impossible. Just a girl you can encounter anywhere in Japan. Every time I wrote or drew something concerning the character of Chihiro and her actions, I asked myself the question whether my friend's daughter or her friends would be capable of doing it. That was my criteria for every scene in which I gave Chihiro another task or challenge. Because it's through surmounting these challenges that this little Japanese girl becomes a capable person. It took me three years to make this film, so now my friend's daughter is thirteen years old rather than ten, but she still loved the film and that made me very happy.

Since you say you don't know what the ending of a story will be when you start drawing storyboards, is there a certain method or order you adhere to in order to arrive at the story's conclusion?

Yes, there is an internal order, the demands of the story itself, which lead me to the conclusion. There are 1415 different shots in Spirited Away. When starting the project, I had envisioned about 1200, but the film told me no, it had to be more than 1200. It's not me who makes the film. The film makes itself and I have no choice but to follow.

We can see several recurring themes in your work that are again present in Spirited Away, specifically the theme of nostalgia. How do you see this film in relation to your previous work?

That's a difficult question. I believe nostalgia has many appearances and that it's not just the privilege of adults. An adult can feel nostalgia for a specific time in their lives, but I think children too can have nostalgia. It's one of mankind's most shared emotions. It's one of the things that makes us human, which is what makes it difficult to define. It was when I saw the film Nostalghia by Tarkovsky that I realised that nostalgia is universal. Even though we use it in Japan, the word 'nostalgia' is not a Japanese word. The fact that I can understand that film even though I don't speak a foreign language means that nostalgia is something we all share. When you live, you lose things. It's a fact of life. So it's natural for everyone to have nostalgia.

What strikes me about Spirited Away compared to your previous films is a real freedom of the author. A feeling that you can take the film and the story anywhere you wish, independent of logic, even.

Logic is using the front part of the brain, that's all. But you can't make a film with logic. Or if you look at it differently, everybody can make a film with logic. But my way is to not use logic. I try to dig deep into the well of my subconscious. At a certain moment in that process, the lid is opened and very different ideas and visions are liberated. With those I can start making a film. But maybe it's better that you don't open that lid completely, because if you release your subconscious it becomes really hard to live a social or family life.

I believe the human brain knows and perceives more than we ourselves realise. The front of my brain doesn't send me any signals that I should handle a scene in a certain way for the sake of the audience. For instance, what for me constitutes the end of the film, is the scene in which Chihiro takes the train all by herself. That's where the film ends for me. I remember the first time I took the train alone and what my feelings were at the time. To bring those feelings across in the scene, it was important to not have a view through the window of the train, like mountains or a forest. Most people who can remember the first time they took the train all by themselves, remember absolutely nothing of the landscapes outside the train because they are so focused on the ride itself. So to express that, there had to be no view from the train. But I had created the conditions for it in the previous scenes, when it rains and the landscape is covered by water as a result. But I did that without knowing the reason for it until I arrived at the scene with the train, at which moment I said to myself "How lucky that I made this an ocean" (laughs). It's while working on that scene that I realised that I work in a non-conscious way. There are more profound things than simply logic that guide the creation of the story.

You have made many films that are set in Western or European landscapes, for instance Laputa and Porco Rosso. Others are set in very Japanese landscapes. On which basis do you decide what the setting should be for any given film?

I have an extensive stock of images and paintings of landscapes that I compiled for use in my films. Which one I choose completely depends on the moment we start working on the film. Usually I make the choice in conjunction with my producer and it really depends on that moment. Because even from the moment I want to make a film, I continue to gather documentation. I travel with a lot of baggage around me, I have many images of the daily life in the world I want to depict. To make a film set in a bathhouse, like Spirited Away, is something I have been thinking about since childhood, when I visited public bathhouses myself. I had been thinking about the forest settings of Totoro for 13 years before starting the film. Likewise with Laputa, it was years before I made the film that I first thought about using that location. So I always carry these ideas and images with me and I make a selection at the moment I start making the film.

Other than some Japanese animation we get to see on this side of the world, your films always express a sense of positivity, hope and a belief in the goodness of man. Is this something you consciously add to your films?

In fact, I am a pessimist. But when I'm making a film, I don't want to transfer my pessimism onto children. I keep it at bay. I don't believe that adults should impose their vision of the world on children, children are very much capable of forming their own visions. There's no need to force our own visions onto them.

So you feel that the films you make are all aimed at children?

I never said that Porco Rosso is a film for children, I don't think it is. But apart from Porco Rosso, all my films have been made primarily for children. There are many other people who are capable of making films for adults, so I'll leave that up to them and concentrate on the children.

But still there are millions of adults that watch your films and who get a lot of enjoyment out of your work.

That gives me a lot of pleasure, of course. Simply put, I think that a film which is made specifically for children and made with a lot of devotion, can also please adults. The opposite is not always true. The single difference between films for children and films for adults is that in films for children, there is always the option to start again, to create a new beginning. In films for adults, there are no ways to change things. What happened, happened.

Do you feel that telling stories in the particular way you do is necessary for us as humans?

I'm not a storyteller, I'm a man who draws pictures (laughs). However, I do believe in the power of story. I believe that stories have an important role to play in the formation of human beings, that they can stimulate, amaze and inspire their listeners.

Do you believe in the necessity of fantasy in telling children's stories?

I believe that fantasy in the meaning of imagination is very important. We shouldn't stick too close to everyday reality but give room to the reality of the heart, of the mind, and of the imagination. Those things can help us in life. But we have to be cautious in using this word fantasy. In Japan, the word fantasy these days is applied to everything from TV shows to video games, like virtual reality. But virtual reality is a denial of reality. We need to be open to the powers of imagination, which brings something useful to reality. Virtual reality can imprison people. It's a dilemma I struggle with in my work, that balance between imaginary worlds and virtual worlds.

In both Spirited Away and Porco Rosso there are people who are transformed into pigs. Where does this fascination with pigs come from?

That's because they're much easier to draw than camels or giraffes (laughs). I think they fit very well with what I wanted to say. The behaviour of pigs is very similar to human behaviour. I really like pigs at heart, for their strengths as well as their weaknesses. We look like pigs, with our round bellies. They're close to us.

What about the scene with the putrid river god? Does it have a base in Japanese mythology?

No, it doesn't come from mythology, but from my own experience. There is a river close to where I live in the countryside. When they cleaned the river we got to see what was at the bottom of it, which was truly putrid. In the river there was a bicycle, with its wheel sticking out above the surface of the water. So they thought it would be easy to pull out, but it was terribly difficult because it had become so heavy from all the dirt it had collected over the years. Now they've managed to clean up the river, the fish are slowly returning to it, so all is not lost. But the smell of what they dug up was really awful. Everyone had just been throwing stuff into that river over the years, so it was an absolute mess.

Do your films have one pivotal scene that is representative for the entire film?

Since I am a person who starts work without clear knowledge of a storyline, every single scene is a pivotal scene. In the scene in which the parents are transformed into pigs, that's the pivotal scene of that moment in the film. But after that it's the next scene which is most important and so on. In the scene where Chihiro cries, I wanted the tears to be very big, like geysers. But I didn't succeed in visualising the scene exactly as I had imagined it. So there are no central scenes, because the creation of each scene brings its own problems which have their effect on the scenes that follow.

But there are two scenes in Spirited Away that could be considered symbolic for the film. One is the first scene in the back of the car, where she is really a vulnerable little girl, and the other is the final scene, where she's full of life and has faced the whole world. Those are two portraits of Chihiro which show the development of her character.

Where do your influences lie as far as other films and directors go?

I was formed by the films and filmmakers of the 1950s, which was the time that I started watching a lot of films. One filmmaker who really influenced me was the French animator Paul Grimault. I watched a lot of films from many countries all over the world, but I usually can't remember the names of the directors. So I apologise for not being able to mention any other names. Another film which had a decisive influence on me was a Russian film, The Snow Queen. Contemporary animation directors I respect a lot are Yuri Norshteyn from Russia and Frederick Bach from Canada. Norshteyn in particular is someone who truly deserves the title of artist.

What will be your next project? Are you working on anything at the moment?

We recently opened the Studio Ghibli museum. Maybe museum is a big word, because it's more like a small shack where we exhibit some of the work of the studio. Inside we have a small theatre where we will show short films that have been made exclusively for the Ghibli museum. I am responsible for this, so I'm currently working on a short film for it.

I'm also supervising a new film directed by a young director named Hiroyuki Morita. The film should open in cinemas in Japan next summer. It's very difficult to supervise another director, because he wants to do things differently from how I would do them. It's a true test of patience.

Does the incredible impact that Spirited Away has had in Japan change anything about your method of working?

No. You never know how a film will play, whether it will be successful or not, or whether it will touch the audience. I always said to myself that whatever happens, big audience or small, that I would not let the results have an impact on my way of working. But it would be a bit silly for me to change my methods when I have a big success. That means my methods work well (laughs).