Six Degrees of Kiefer Sutherland: The World of Anime Voice Acting

- published

- 3 May 2006

The treatment of sound has been one of the invisible elements of Japanese animation's exports abroad. Inured to the need to replace voice tracks in different territories, Japanese animation sound is usually recorded in two distinct parcels - a voice track laid down with the actors, and the Music and Effects (M&E) track comprising all other elements. In the days before digital copying and back-ups were possible, some M&E tracks did not survive as separate entities, seriously hampering the chances of an anime getting a foreign release.

Voice acting in the earliest anime was not part of the finished work, since anime was in existence for a decade before the introduction of audio. Instead, anime would be screened to a musical accompaniment, although many would also employ a live benshi (narrator) to fill in dialogue and story elements in the style of similar performances in the Japanese puppet theater or magic lantern shows. Voice work in early anime was often of secondary concern, with "actors" pulled in from available staff. When casting the two combatants in Benkei vs. Ushiwaka (1939) director Kenzo Masaoka chose Mrs Masaoka to play the diminutive hero, and himself as the hulking brute Benkei.

THE FIRST VOICE ACTORS

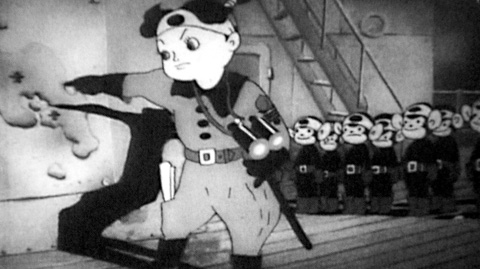

Dialogue from several American films was stolen to add exotic foreign language scenes to wartime propaganda, including snatches from Popeye's enemy Bluto, who appears as an Allied soldier in Momotaro's Sea Eagles (1943). Sometimes, the effect can be unintentionally surreal - in the middle of the battle sequence in Momotaro's Divine Sea Warriors (1945), an American voice can be heard hailing a taxi. The first genuine English-language voice actor in anime appears in the closing moments of the same film, in the form of the tremulous and cowardly British soldier who attempts to renegotiate the terms of his surrender. The uncredited actor is clearly a native speaker, but with a strange delivery that seems either to be a calculated attempt to make his dialogue unusable, or perhaps, more chillingly, the sign of a man in genuine fear for his life.

In the 1950s, as Toei Animation and Mushi Production began to make animated features in imitation of Disney, famous Japanese personalities were often chosen to appear in anime, although not always on account of their acting skills. Osamu Tezuka's Arabian Nights (1969) and Cleopatra: Queen of Sex (1970) bizarrely include vocal performances from a number of famous Japanese authors, including Shusaku Endo, Yasutaka Tsutsui and Sakyo Komatsu.

The rise of television saw an exponential rise in the number of vocal performers in Japan, creating an entire voice acting industry in order to dub foreign television productions into Japanese. Anime voice acting often exploited this fact with casting decisions whose relevance is all but lost on a non-Japanese audience, hiring the Japanese "voices" of famous American screen stars to portray anime characters with similar profiles. Yasuo Yamada, who was until his death the voice of Lupin III, was also renowned for playing Clint Eastwood, while Lupin's sidekick Jigen was played by Kiyoshi Komori, the Japanese voice of Lee Marvin. Similar casting "coincidences" continue to the present day, with numerous big-name anime voice actors also playing big names from Hollywood, although it is less common for a Hollywood star to have one single Japanese actor play all their roles.

The popular anime voice actors of today include Akio Otsuka, best known as Batou in Ghost in the Shell, who is also the voice of Jonathan Frakes (Commander William Riker) in Star Trek: The Next Generation; Kappei Yamaguchi is the voice of both the titular Inu Yasha and Bugs Bunny; and the versatile Koichi Yamadera has not only voiced Cowboy Bebop's Spike Spiegel, but also roles by Jim Carrey, Eddie Murphy, Robin Williams and Tom Hanks.

Many famous voice actors end up typecast - consistently given the same kind of role, be it as juvenile lead, a maverick rebel or a slow lunk. This can limit the audience's perception of their abilities, but can also prove to be beneficial on fast schedules - an actor who has played three hot-headed heroes in the past week, probably knows what he's doing when given a fourth. Sometimes anime can exploit these associations in reverse - Hideaki Anno's Neon Genesis Evangelion famously cast several prominent voice actors against type, in a decision that generated superb performances. Anime voice actors are also liable to enjoy spin-off careers in radio and music, and many have their own radio shows or albums. Modern anime exploits this by using voice actors in radio dramas or games as an experiment to test the market for a later anime version.

Voice acting in Japan is usually recorded while the actors watch the animatics (in Japanese, the "Leica reel") - a precisely timed video of storyboards that allows them a sense of how the finished product will look. Many voice recording facilities in Japan run around the clock, in order to get the best returns from their investment in expensive machinery. This, along with union rules, has made child-actors rare in anime voice work, tending only to appear in movie productions, which require less studio time than a long-running series, and can also afford the higher prices of daytime booking. In the cheaper, longer-running worlds of video and TV, child parts are often played by adult women, notably Masako Nozawa, who is the Japanese voice of both talking pig Babe (1995) and Dragon Ball Z's Goku, and Megumi Ogata, who has voiced male anime protagonists from Evangelion to Yugi-oh. Most Japanese voice actors are professionally trained as such, and hence know to monitor and preserve the talent that earns their living. In one notable choice, Akira Kamiya, the voice of Ken in Fist of the North Star, decided upon his trademark high-pitched attacks because falsetto yells would be easier to repeat and maintain over a long series than gruff growls. Such considerations can often elude less experienced actors abroad, some of whom have temporarily damaged their vocal chords, lost their voices, or been forced to drop out of long-running productions. A three-day recording session of a snarling bad-guy part can render an actor's voice unusable for the following week.

ENTER THE FANDOM

The concept of a voice acting fandom first arrived in Japan in the early 1980s, with newly founded magazines such as Newtype and Animage in search of fresh subjects for articles. The foundation of such journals also coincided with a move into a new form of anime industry, where cross-promotional appeal and spin-offs were suddenly desirable for audiences older than the former target demographic of children. One of the stars of early voice acting fandom was Mari Iijima, who provided not only the speaking voice of Lin Minmei in Macross, but also her singing voice in a number of spin-off record releases.

For the video-based anime industry, with a primarily male fan-base, a heavy concentration on voice actresses was inevitable, with some of the most popular stars including Megumi Hayashibara (the female Ranma ½, but also Audrey Tatou in Amélie), Kotono Mitsuishi (the lead in Sailor Moon, but also sometimes heard as Cameron Diaz and Natalie Portman), Aya Hisakawa (Sailor Mercury and Natalie Portman, again), and Chisa Yokoyama (Pretty Sammy in Tenchi Muyo, but also Winona Rider and Alicia Silverstone). Anime voice actors, with the easy assumption of supposedly glamorous lives out of the studio, are also popular choices as columnists in magazines, and not merely those associated directly with the anime world. Fumi Hirano, who was once the voice of Lum in Urusei Yatsura, still writes a column on the world of fish for Big Comic. This is not quite as bizarre as it may first seem, since she left the acting business to marry a wealthy fish market entrepreneur.

Voice acting in the Western world has developed similar personality cults, beginning with the realisation that many American voice actors were often locally available, easy on the eye and good with crowds - all excellent reasons to invite them to conventions. Many American voice actors have become fixtures on the convention circuit, including stars from anime of yesteryear such as Corinne Orr (Speed Racer) and Amy Howard Wilson (Star Blazers). Voice actor attendance at conventions has grown exponentially during the 1990s and beyond, particularly since Japanese guests can be expensive to invite and may not speak English. It is not uncommon for American anime conventions to have many more American voice actors than Japanese guests, leading to convention events concentrating more on actors' subsidiary skills than anime itself - improvisations, panel games and skits.

STUNT CASTING

Whereas video anime tend to use relative unknowns, often rendered all the more unknowable by the common use of pseudonyms to preserve union status, anime feature releases in America regularly use "stunt-casting" - the use of actors famous elsewhere. Incidences date back to the use of Frankie Avalon in Alakazam the Great (1960), and have included cameo anime performances from Orson Welles and Leonard Nimoy (in the Transformers movie). This has even happened in Japan, where the producers of the Armitage III movie Polymatrix decided to make it exotic by hiring foreign actors and releasing the movie in English in Japan, with the voices of Kiefer Sutherland and Elizabeth Berkley.

American stunt-casting roles has become even more noticeable in recent years with the release of Studio Ghibli films in America, utilising such talents as Lauren Bacall and Jean Simmons (Howl's Moving Castle), or Kirsten Dunst and Debbie Reynolds (Kiki's Delivery Service). Similar casting decisions have been made with regard to the voices in some modern porn anime, in which erotic stars such as Asia Carrera, Kobe Tai, and Alexa Rae are used to dub anime, in the presumed hope that fans of their live-action work will also pick up their voice-overs for the sake of completeness. This was also tried with some erotic anime in Japanese, such as the casting of adult video starlets in the original Japanese language track of Adventure Kid, although this backfired when the performers appeared demonstrably unable to actually act.

Players of the actor game "Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon" will be disappointed to hear that although he voiced the eponymous Balto (1995), he has not appeared in an anime. However, he did co-star with Kiefer Sutherland in Flatliners (1990), information which may be regarded by Midnight Eye as being of a frivolous nature, but is liable to be of considerable use in numerous late-night bar games in the film and anime worlds.

(Jonathan Clements played the mutant general V-Daan in the UK release of the anime Beast Warriors. His most recent acting role was an underrated Albanian-language performance as a Kosovan cockle-picker being eaten alive by an invisible vampire, in the Doctor Who CD spin-off UNIT: Snake Head. He is the co-author of the acclaimed Anime Encyclopedia and The Dorama Encyclopedia.)