Return to Yubari

- published

- 24 April 2013

Cold climate, warm festival. This succinctly sums up the Yubari International Fantastic Film Festival, held every winter on Japan’s snow-covered northern island of Hokkaido. It’s one of those places that have that rare magic only a few film festivals possess: a down-to-earth atmosphere of filial friendliness that disappears as soon as the event closes its doors and its participants disperse, only to miraculously re-emerge on opening day the following year – different guests, staff mutations and venue changes notwithstanding. There are many festivals that show good films, but not all of them possess a signature atmosphere, let alone this particular quality. The International Film Festival Rotterdam and Frankfurt’s Nippon Connection are two other examples.

It had been five years since I last visited Yubari (as a jury member in 2008, the festival’s "resurrection year" after the town’s bankruptcy had prevented the 2007 edition from taking place), but the magic had been retained: the gathering of all the guests at Sapporo airport, the unsteady walks across slippery snowy streets, the locals’ home cooking, the frozen limbs during the legendary outdoor stove party, and the after-hours drinking at karaoke bar Grace and the cosy cluster of tiny watering holes named, without a hint of irony, Bali, where the famous, the hopeful and the anonymous rub shoulders and clink glasses.

This year’s jury was presided by Shinya Tsukamoto and consisted of filmmaker Daihachi Yoshida (Funuke Show Some Love You Losers, The Kirishima Thing), actor Hiroshi Yamamoto (a familiar face from Nobuhiro Yamashita’s films), connoisseur of Korean cinema Darcy Paquet, and Alice Yoo, programmer at Yubari’s Korean sibling, the Puchon International Fantastic Film Festival (PiFan).

Winter Alpaca

The Off-Theater competition was, as is typical for Yubari, eclectic to say the least – or a mixed bag to put it in other terms. Two French shorts seemed mainly thrown in to pad out screenings to feature length: the one-joke Happy Birthday, Mr. Zombie and the somewhat confused would-be fairy tale Sacha the Bear. Other entries wore their incompetence on their sleeves: the Korean entry Boys’ Story told its tale of teenage runaways on the mean streets of Seoul in purely soap-operatic terms, though Tomohiko Iwasaki’s Ami? Amie? (Ami? Amie? Tsukiatteneeyo!) was clunky but also possessed a certain charm, largely thanks to an engaging young cast. Ken Kawai’s From Here to Nowhere, previously screened in competition at the Pia Film Festival, showed the inexperience of its 23-year-old first-time director, but also occasional glimpses of his potential. Its lead actress Yukino Arimoto deserves special mention for her portrayal of an amoral young drifter, while Maori Kannonzaki did indeed receive one from the jury for her performance in veteran director Masato Hara’s Soar (Anata ni Ite Hoshii).

Given the uneven nature of the competition line-up, the jury’s final decisions didn’t come as much of a surprise, since they went to the three standout films. Governor’s Prize winner Winter Alpaca (Fuyu no Arupaka) tells of a dumpy young woman whose one passion in a dull life, taking care of a flock of the titular mammals, is threatened due to debts she owes to a loan shark. She must pay back what she owes or see her beloved animals taken away and sold. This dime-a-dozen premise is elaborated in a series of skits in which the protagonist (the excellent Ayumi Nigo) tries her hand at various professions, inevitably failing in ways that are at once drily humorous (sometimes laugh-out-loud funny) and deeply poignant. Working in the tradition of Aki Kaurismäki and Nobuhiro Yamashita, director Yuji Harada is clearly a talent to watch for his ability to express conflicting emotions through a shooting style that eschews all visual trickery. His one-take scenes are modest marvels.

The Special Jury Prize went to Yuri Kanchiku’s light-hearted and free-spirited A Case of Eggs (Keranhanpan), a funny and sexy comedy about a Japanese photographer’s salacious trek around Seoul in search of pretty girls to shoot and seduce, and the unfortunate young woman who has to serve as his interpreter along the way. With him not speaking a single word of Korean, he must rely on her assistance at every turn, including in his seduction of a beautiful dancer. But who is he actually attempting to coax into his bed? With a charming lead turn by Jun Murakami at his most charismatic, A Case of Eggs was originally part of an omnibus feature, but was excised from the prints released theatrically in Korea. Rumour had it that its exile was due to the film’s frank treatment of sexuality, but Darcy Paquet expressed his doubts, given the not dissimilar subject matter of other films produced in the country.

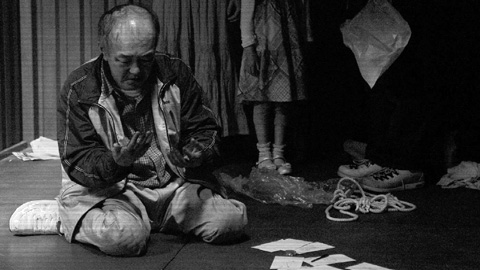

A Case of Eggs

The Grand Prize deservedly went to Yukihiro Toda’s There Is Light (Kurayami kara Te o Nobase) about a sex worker’s first experiences serving disabled clients. Like A Case of Eggs, it treats its subject with equal doses gravitas and humour, through with a docudrama-like approach that points to the project’s origin as an NHK television documentary. Regardless, as a fiction it works, thanks to a frank and unprejudiced approach and a consistent narrative motif about choices one makes in life and the desire to keep moving forward, no matter what setbacks you may encounter. Occasionally explanatory yet never heavy-handed, There Is Light features a fine lead performance from Maya Koizumi, who reveals more acting talent than anyone has the right to expect from a swimsuit model, with able support from the ever-reliable Kanji Tsuda as the civil servant turned pimp and wheelchair-bound comedian Hawking Aoyama as a client who keeps insisting on receiving "the real thing".

The perceptive reader will have noticed that none of the three prize winners would qualify as what is commonly referred to as "fantastic" films, and are unlikely to pop up at other festival that market themselves in this manner. I’ve previously explained how the unique nature of Yubari makes it more than a festival of genre movies, but at the same time there was no shortage of horror, fantasy and sci-fi this year either. Standouts among the genre fare included Yudai Yamaguchi’s Abductee, a Cube-like tale of a man who wakes to find himself trapped inside a locked container that remains riveting and surprising in ways that many of its director’s previous works never were. Omnibus film The ABCs of Death has a great concept but is inevitably uneven, although its highs are steep indeed: Marcel Sarmiento’s astonishing D is for Dogfight has to be seen to be believed, Timo Tjahjanto’s L is for Libido is a gleeful celebration of stylish excess and taboo-breaking, and Yoshihiro Nishimura’s Z is for Zetsumetsu packs as many politically offensive jokes (plus the requisite oversized penis obsessions) as it possibly can into a lurid, five-minute riff on Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove.

Abductee

A special tribute to director Hajime Ohata offered the opportunity to catch up on this talented filmmaker’s 2009 Yubari Special Jury Prize winner A Big Gun (Daikenju) and its follow-up, the jaw-dropping The Fly-meets-The Exorcist-meets-Godzilla freak-out Henge (2012). Added bonus was Ohata’s latest, the made-for-TV short Trick or Treat, which, while offering a solidly told assassination plot, seemed positively subdued alongside his previous outings.

After making a splash with his "super organic battle action" movie Encounters last year, Takashi Iitsuka returned to Yubari with Ninja Theory, a new live-action puppet adventure in which the daily routine of a group of ninja heroes protecting a small town from vandalism and dog droppings is disrupted when one of its members gets possessed by an evil spirit. Like its predecessor, Ninja Theory features figurines manipulated with strings, though there is much less uncontrolled dangling to be seen here. Thanks to a scholarship, the director could hire professional actors to provide the voices this time. A step forward in terms of craft, then, and never less than entertaining, though one can’t help but wonder if Iitsuka can keep his style and his storytelling from growing gimmicky and stale.

Melody of Funhouse

More impressive as animation, as well as from a cinematic viewpoint, is the film that screened alongside Ninja Theory, Toshiko Hata’s colourful and energetic mixture of live action and stop motion animation Melody of Funhouse, in which the monster-mashing antics of a toy rock band make a little girl discover the joys of music. The previous film by this Tokyo University of the Arts graduate was the beautifully eerie Rootless Heart (Samayou Shinzo), whose tale of a haunted wooden dummy that steals its victim’s hearts was worthy of the Brothers Quay.

Pitching male versus female directors was the very outset of the Banana vs. Peach series of screenings, which the ladies won by a landslide thanks to the presence of such profusely talented contestants as Chihiro Amano, Miyuki Uehara and Yukiko Sode. Keep your eye on your local film festival line-up for these three names in the near future. Interesting takes on gender relations could also be seen in Naofumi Higuchi’s The Intermission, a film made to bid farewell to the venerable Cinepathos theatre in Ginza, Tokyo, forced by the authorities to close its doors for (dubiously concocted) earthquake-related safety reasons. More on this rich and rewarding film soon.

The Intermission

Much enthusiasm was found at the outer fringes of the festival as well: the young organizers of the Student Splatter Film Festival (Gakusei Zankoku Eigasai) literally painted the town red, while the globetrotting Cinema Caravan troupe had set up a tent in front of the main festivla venue from where they projected short video works onto a four-meter high wall of pristine white snow – as well as serving warm saké, takoyaki and hotpot. The other meaning of the word fantastic fits Yubari equally well.