Midnight Eye’s Best (and Worst) of 2014

- published

- 3 February 2015

Gun Woman

Tom Mes

The year 2014 overall brought a consolidation of last year’s observations about insularity and stagnation. Naturally, in a country that keeps making an average of 400 new feature films a year, there are always pearls to be found among the swine, though whether any of them will actually be given room to find an audience beyond the occasional festival screening remains a moot point.

In this regard, by far the year’s most refreshing discovery was Gun Woman, shot largely in the USA by LA-based maverick Kurando Mitsutake. Made for next to nothing, it offers thrills aplenty and features an absolutely electrifying physical performance from cult actress Asami. It won the Special Jury Prize at the Yubari International Fantastic Film Festival (from a jury I was part of) and has gone on to receive wide commercial distribution internationally.

A number of films this past year fell into the "Or what" category (as in: "Are you including these in your top 10 or what?"). The best of these is Ken Ochiai’s Uzumasa Limelight, a sincere and enjoyable homage to the workhorses whose blue-collared shoulders carried the Japanese studio system of yore, but who are struggling to survive in the days of CGI and here-today-gone-tomorrow idols. Ochiai’s film is thoroughly likeable and well intended, but it fails to stir up much passion. Hirokazu Koreeda’s Like Father, Like Son was fair and amiable, but also seriously undermined by the too obvious development (what studio readers call a "character arc") undergone by the already not terribly subtle protagonist. The Tale of Iya by Tetsuichiro Tsuta was a widely praised indie effort that had two great things going for it: landscape cinematography and Min Tanaka. Problems in other departments, notably the portrayal of the foreigners and their tensions with the locals, finally made its 169 minutes a chore to sit through. Sion Sono’s Why Don’t You Play In Hell, finally, is an overlong, forgettable placeholder that wishes it were a fan favourite, but forgets to make an effort. As erratic and hastily put together as the fictional movie shoot it portrays, it relies on lame jokes, predictable references and obvious money shots in its attempts to play to the galleries. (I have yet to see Tokyo Tribe, and while the word on that one is good, I have long since learned that anticipation and quality are two different things.)

Best Japanese films, in no particular order:

Gun Woman (Nyotaiju, dir: Kurando Mitsutake)

LA-based filmmaker Mitsutake puts every dollar on the screen in this riveting, trashy actioner that many have compared to 1980s Canon exploitationers or early 1990s V-cinema. Unlike most of those productions, however, this movie delivers what the poster promises. Independent filmmakers everywhere – but especially in Japan – take note: this is how you get your film seen and sold.

Tale of a Butcher Shop (Aru Seinikuten no Hanashi, dir: Aya Hanabusa) + The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness (Yume to Kyoki no Okoku, dir: Mami Sunada)

Two fly-on-the-wall documentaries about people working and coexisting in intimate environments: one focuses on a family that has been working as artisanal butchers for generations, the other portrays the goings-on at world renowned Studio Ghibli during the final months of production on Hayao Miyazakis The Wind Rises (Kaze Tachinu, 2013). Both films are intimate portraits of artisans and artist, while at the same time also being hugely evocative of wider issues in Japanese society and the world at large.

Over Your Dead Body (Kuime, dir: Takashi Miike) + The Mole Song: Undercover Agent Reiji (Mogura no Uta Sennyu Sosakan Reiji, dir: Takashi Miike)

Miike’s two-pronged offerings of the year were, characteristically, diverse – diametrically opposed, even: one a meditation on performance and narrative in which stillness speaks louder than action, the other a hair-sprayed, panther-bloused and snakeskin-booted action comedy built around a gangly idol du jour who mugs his way through a labyrinthine underworld intrigue filled with larger-than-life villains. Either way the results, as they say, delivered.

Fires on the Plain (Nobi, dir: Shinya Tsukamoto)

Tsukamoto finally got to make his long-cherished pet project, though on a budget that is noticeably straining to support his vision of hell on earth during the Pacific War. And not a day too soon, what with Japan’s ruling class practically falling over itself to return to the good old days of militarism and territorial expansion, when one could go plunder and rape one’s neighbours and – oh wait, there’s that nasty reminder – die in agony of very nasty diseases in a sweltering jungle.

Forma (dir: Ayumi Sakamoto)

This winner of prizes in Tokyo and Berlin will sharply divide audiences with its rigorous mise-en-scene inspired by European art cinema (Haneke and Akerman loom large). A film with the tagline “A 145-minute antithesis” is not likely to receive too many unsuspecting patrons, but even those that found it hard to sit through will acknowledge that the careful build-up of the characters, their links and backgrounds was masterfully handled, especially for a first-time feature.

School Girls’ Gestation (Ryugu no Tsukai, dir: Atsushi Ueda)

Winner of the Governor’s Prize in Yubari, this is a caustic, absurdist, yet charming and well-observed comedy about small-town life, revolving around a group of schoolgirls who collectively decide to become pregnant. Though based on an actual event that happened in Massachusetts some years ago, School Girls’ Gestation is very much a product of post-Fukushima Japan.

Fuck Me to the Moon (dirs: Quanah Takahata, Hirohito Takino)

This one only just missed out on an award in Yubari. It has hardly screened at any other festivals since, possibly because it doesn’t really find its footing until about one-third into the film. From there, this comedy about an inseparable pair of loser wannabe-musicians lusting after and being wrapped around the finger of a contemporary Princess Kaguya becomes increasingly endearing, and ends with an unforgettable climax.

The Worst:

The World of Kanako (Kawaki, dir: Tetsuya Nakashima)

Ex-cop Koji Yakusho, his self-loathing sublimated into hatred of an assumed sick society, slaps, punches, crashes, rapes and kills his way through a repetitive film that tries to make up with blood and brutality what it lacks in sense. An unhinged middle-class reactionary, Yakusho’s character is the object of vicarious identification, revealing this film’s resolutely middle-aged male gaze.

The 70s retro pastiche opening credits loudly declare that all characters will “Go to Hell!”, but it’s a hell entirely imagined by Nakashima and his aging producers.

Kanako’s world is a hidden den of sin, in which all teenagers binge on parties, drugs, booze and sex, and where they inevitably turn into delinquents, apprentice gangsters and killers – or meat for anonymous ojisan rapists. At heart, all of this is no different from the old ‘taiyozoku’ template of wasted youth as menace to society, except here the social relevance is an illusion from the minds of middle-aged Shinzo Abe supporters.

Nakashima’s statement that this is another expression of his ‘dark view of humanity’ makes for a nice sound bite, but the claim falls flat because none of his characters remotely resemble human beings (see also previous exercises Memories of Matsuko and Confessions). The titular Kanako is emblematic in this regard, as she is merely a hollow shell and cypher. Paul Schrader’s Hardcore this ain’t. At best, The World of Kanako is candy-coloured conservatism, but this would mean lending a political dimension to something that is really too naïve to manage a political thought.

Uzumasa Limelight

Jasper Sharp

I’m really at a bit of a loss coming up with my best films for this past year. While I think I’ve made more of a concerted effort to watch new releases in 2014 than over the previous couple of years, I can’t think of anything I saw which I could really get that passionate about. Partly this could be down to the way I watched a lot of stuff – a lot on online screeners, for example, which is hardly a way of getting the measure of film’s full impact compared with the full theatrical experience.

That said, release windows being as short as they are nowadays (and ticket prices as high as they are in London), a lot of films passed me by before I had a chance to see them in the cinema, Boyhood and Under the Skin being the perfect examples – they both sound like the type of film I’m pretty sure I’d enjoy, but I keep meaning to pick up the Blurays in the same way I keep meaning to pick up Arrow’s Mario Bava Blurays and loads of other stuff that has emerged on the home-viewing market over the past 5 years. Stuff like Mike Leigh’s Mr Turner, too, I’ll probably wait till it turns up on television.

It sort of reaffirms my fears about the switch to digital cinema. Aside from the size of the image, there just doesn’t seem to be that much of a tangible difference between theatrical and home viewing any more (at least the Bava films were shot on a medium that was meant to be projected rather than viewed on a TV screen, making me more likely to go to the cinema to watch these kind of 35mm screenings whenever the chance presents itself). Market forces seem to be doing their best to destroy the medium too. Today’s critical choice is tomorrow’s bargain bin offering, while yesteryear’s trash is considered today’s treasure. With so much to choose from cinema’s 120-year past available on DVD and Bluray, is there any real necessity to keep up with the continuing swathes of new releases each year?

I’m being a little provocative here, because actually most of my Top 5 are films I did see on a big screen with a big audience – several of which have yet to see release in the UK and were caught at Montreal’s Fantasia Film Festival (which also really highlights the fact that I should make more of an effort to get a bit more active again on the festival circuit rather than just more frequent cinema trips). Now there was a time in my late-90s cinephilic heyday when a film like Kumiko the Treasure Hunter (starring that go-to-girl for Japanese women abroad roles, Rinko Kikuchi) would have gone on a fairly substantial run in the UK and would even be something of a talking point among more casual viewers. I note now that there is a release lined up over here in a few months time, but I’m wondering if it will cause quite the same breakthrough splash that, for example, a not dissimilar title such as Fargo (being the obvious reference point) did 20 years ago, of Sideways even ten years ago. Incidentally, now I’ve referenced Alexander Payne (executive producer on Kumiko), his last film Nebraska makes my top 5 because after such a low-key release at the end last year, its Oscar nomination was enough to get it revived for my local multiplex early in 2014, which is how I saw it.

This problem of when does the year begin and end is a familiar one with these end-of-year lists, especially as Midnight Eye’s traditionally come a month later than most others (my Sight and Sound solicitation came a good two months before 2014 was out, for example). There’s also always the element of looking over one’s shoulder to see what everyone else loved, whilst trying to assert one’s own identity by flinging in a few wildcards or obscurities that most people have never even heard of, yet alone seen. I’ve tried to be honest with my choices, reflecting films I just enjoyed watching rather than what others have praised.

In the meantime, casting one’s eye back over such a long period really makes one aware of the fanfare and hullabaloo that the industry thrives upon. Steve McQueen’s 12 Years a Slave (2013), for example, was the very epitome of a “quality” film, but 9 months after heading to the cinema to see it, I’m struggling to remember if it was actually really that good or important or if I ever need to see it again. The Bababook, too, was an intelligent and inventive horror, I thought, but somehow it didn’t really make the impact on me that it seems to have made on others. Interestingly, when one looks at the Sight and Sound polls, one notes that these particular films only got 3 and 2 votes respectively from the 112 critics polled. Meanwhile, I was the only person to vote for 4 out of the 5 films included on my list, which I’m reproducing rather than reworking for Midnight Eye. There’s a couple of things that I’ve seen in the meantime that would make the grade, but as they’ve not been shown in the UK yet, I think I’m going to hold them back for next year.

In the meantime, here’s my top 5 worldwide, in no particular order:

The Duke of Burgundy (Peter Strickland, UK, 2014)

Kumiko the Treasure Hunter (David Zellner, US, 2014)

Closer to God (Billy Senese, US, 2014)

The Inbetweeners 2 (Damon Beesley, Iain Morris, UK, 2014)

Nebraska (Alexander Payne, US, 2013)

As for Japan, well, rather similar to last year, I’ve not kept my eye quite so close on the ball when it comes to new releases. Still, if I’ve complained over the past few years that Japanese cinema has been increasingly insular and irrelevant, at least to my life, then nothing this year made me change my mind. My favourite mainstream production this year was probably Ken Ochiai’s Uzumasa Limelight, which provided a cosy hark back to a time when Japanese cinema was so much more distinguished than it is now. It didn’t really do anything new, but what it did do, it did well, and there was a refreshing warmth to it. I was happy to part of the jury at Fantasia Film Festival that awarded it the Cheval Noir award for Best Film.

Elsewhere at Fantasia I saw a film that for me was symptomatic of everything that makes my flesh crawl about Japanese cinema and its overseas appreciation in the wake of Sion Sono and Tetsuya Nakashima’s Confessions. Eisuke Naito’s Puzzle was another offering in the very Japanese vein of sociopathic high-school kids pitting themselves against the establishment – in a particularly repellent scene, a pregnant teacher is tied spread-eagled on the floor and forced to miscarry after a microwave is dropped on her belly (or was it a TV? I’m trying to block the scene from my memory…). This isn’t quirky, it’s not surreal, it’s not whacky, it isn’t cool. It is just unpleasant. I haven’t felt such an adverse reaction to a movie in years.

There was more interesting and uncompromising stuff from the indie sector, as usual – with his new adaptation of Shohei Oka’s Fires on the Plain, I think Shinya Tsukamoto has delivered one of his most impressive, mature and powerful films to date, although the production certainly suffers from a tangible lack of budget.

Meanwhile Flashback Memories 3D, an eccentric music documentary about a didgeridoo player with severe retrograde amnesia following a traffic accident, was a typically inventive and entertaining exercise in turning such micro-budgetary constraints into advantages, like it director Tetsuaki Matsue’s 2010 Live Tape. This is a couple of years old now, but I only caught up with it recently – admittedly the end results might all be a bit too minimalistic for some tastes, but it is films like this that provide me with the last few rays of hope for a national industry which has been stagnating for some years now.

Still, we always have the old classics to go back to.

Event of the year:

I’d be lying if I didn’t say that the world premiere at Fantasia of my own filmmaking debut, The Creeping Garden, a documentary about plasmodial slime moulds co-directed with KanZeOn’s Tim Grabham, wasn’t among the high points of my life. I’ve had a whale of time at all the screenings of this film I’ve been present at, and it has been wonderful to open the door on a subject that no one really knows anything about and talk with audiences after they’ve seen it. The whole experience of making a film and getting it shown has been a real education for me, and heavily informed the way I now look at cinema. It is also what has kept me so preoccupied throughout most of 2014 that I’ve not really kept up on as many new releases as I’d have liked.

Like Father, Like Son

Roger Macy

In 2014 I watched nearly 500 films of which nearly all the viewings were in theatres of some sort. In a year in which I did not visit Japan, just over 100 were Japanese, but only about 30 were recent releases. So I’d like to mention five recent ones and five from earlier.

The happy news is that there have been some good examples of thoroughly convincing character acting in completely believable dramas - whilst still pitched to appeal to a young audience. We’ve been able to expect fine directing of actors from Hirokazu Koreeda, whose Like Father, Like Son got its western release at the beginning of the year, but I was equally impressed by Be My Baby (Koi no Uzu, 2013), in which Hitoshi One directed a pool of young talented actors from the ‘Cinema Impact’ initiative. Be My Baby derives from a play by Daisuke Miura, which I feel gave much to its rich understanding of characters who would not usually suggest depth. Perhaps One’s ending rather spoilt the plausibility, but I felt privileged to hear from a group of professional actors still forming their careers at Udine together with the producer of Cinema Impact, Masashi Yamamoto.

The Light Only Shines There (Soko no minite kagayaku, 2014), directed by Mipo O had first class acting from the leads, especially Chizuru Ikewaki. Even Fuku-chan of Fukufuku Flats (Fufukusho no Fuku-chan, 2014, directed by Yosuke Fujita) was far less goofy than its title suggests, also going for a tight-knit study of characters. Miyuki Oshima has instant face recognition in Japan as a female comic but you could watch her straight acting of a male role here without realizing this, so neatly finessing any gender trap towards the audience.

Equally fine acting, albeit tragedic, was seen at Nippon Connection who showed Backwater (Tomogui, 2013). It would win the most ‘bad sex’ awards since the Japan creation myth, which, I presume, is one of the story devices in the shadows of Shinya Tanaka’s original novel, Dog Eats Dog. The convincing modern setting, however, is linked to the end of the Showa era. Shinji Aoyama’s direction always uses space intelligently. If ‘Backwater’ can be read as a parable of modern Japanese culture, it’s the dramatic muse that might show Japan’s genre-bound cinema a way out of its own islands as, arguably, it has done before.

Most theatrical screenings abroad of archive Japanese film have been thematic rather than director-linked, although there have been helpful retrospectives of lesser figures - of Noboru Nakamura at Berlin, Yoshitaro Nomura at Bradford and Ko Nakahira in German cities. Perhaps Mud-splattered Purity (Dorodarake no Junjo, 1963) shone brightest for me out of Nakahira’s. The Nomura film that hit me hardest was Kichiku, (1978). This has always been translated as The Demon, although it seemed to me that there was more than one. It wasn’t a five-handkerchief movie because the cruelty to children felt so tense that the dam did not break for me until afterwards. Most harm that occurs to children in films is just the smoke and mirrors of editing, of which the actors are not aware. But here they received physical tormenting - food being forced down a toddler – as well as mental, in that they had quite long takes in which they must have understood the cruelty which their characters suffered. They may also have known it was based on a true story. The music was well held off for the most part and was also haunting.

Bologna in 2014 concluded a three-part survey of early Japanese sound films. The sound element was generally the weakest part although directors tried various stratagems to make the most of this technical weakness. However, the retrospective brought out of obscurity a range of films never seen in the West, even when by relatively familiar directors such as Hiroshi Shimizu. But I’ll single out the western premiere of Yasujiro Shimazu’s Our Neighbour Miss Yae (Tonari no Yae-chan, 1934) for its dialogue of the modern and the conservative, even if the film did have some continuity errors that alarmed my inner train-otaku. Hiromasa Nomura’s Our Happy Day (Hitori Musuko, 1933) stood out for its humour and accomplished sound-track.

Lighting in films has not been an aspect to which I have paid much attention. So the book by Daisuke Miyao and the retrospective that showed at New York and Berlin were very instructive, although the historical and political contexts of so many unseen films still kept my attention. By a fluke of timing, I saw the 1942 film, Hawai Mare Oki Kaisen at both. The film’s reputation for realistic action did not disappoint but it was billed as The Sea Battles off Hawaii and Malaya at New York even though it had no mention of Malaya. It was an edit of 73 minutes instead of 116 minutes, in different order. You might think that someone at a major museum would be exercised about their unique film’s historical function (in French). Alas, I have too many unfinished tasks to pursue it at the moment.

Several films this year accidentally demonstrated how vital the story framing and music were to the reception to a film. Add some scary music and Our Neighbour, Miss Yae could be made into a cliffhanger, both literally at the uncompleted bridge, and more broadly as social decline. ‘The Sea Battles off Hawaii (Export Version)’, as I will provisionally rename it, ended with groans from the New York audience as the US navy sank into Pearl Harbor. I don’t think the heckling of ‘Five Scouts’ about ‘propaganda’ at Berlin would have happened if others in the audience hadn’t tried to frame the film as patriotic heroism. But I guess it’s too early to tell, what with it only being 75 years after that particular war.

Moving onto non-Japanese films, something similar happened at the screening of Operation Sunflower, 2014, at the UK Jewish Film Festival, about the clandestine obtaining by Israel of the atomic bomb. The absence of any music made the audience into the mood-music of the film. Every time Mossad eliminated another obstruction to the triumph of Ben Gurion’s will, the clucks of approval got louder. The film also had its own framing device - the story is told from a Tel Aviv bomb shelter, due to a real-time televized (or more accurately a reality-tv framed) ‘missile-threat’ from Iran. Since the story has to end, we are already forced to view the inner story as justified nuclear blackmail which, in due course, is the reality-tv resolution. All this certainly contributed to my edginess and it’s the only film I have ever seen silhouetted against a scuffle in the cinema. UKJFF security reassured me afterwards it was OK, since it was not an anti-Semitic attack. Incriminating testimony, I thought. I’ve usually flinched from voting for a ‘worst film’ award, but I have no hesitation in voting this film as worst in all possible categories.

Now for the best of non-Japanese films:

Kreuzweg (The Stations of the Cross, 2014) directed by David Brüggermann was my top favourite for its convincing portrayal of religious fundamentalism in a western family setting. It’s also two reasons why the Berlin award to Haru Kuroki for ‘best actress’ was complete nonsense. (I have my own conjecture as to how that might have happened. Picture a hung jury after some hours of arguing the merits of Lucy Aaron and Anna Brüggermann, and possibly others. Then someone mentions the ‘star’ of ‘The Little House’ by way of relief and to try and find out what role the young woman in the kimono last night had played in the movie. But no one else was prepared to admit that they didn’t know, either, so no one could articulate a critique against her and, in a sudden wave of unnecessary guilt about preoccupation with figures close to home, the kimono was waved through. Anyway, I’m happy that I can find a way of not putting a knife in further to that well-meant Japanese film of modest achievements.)

Le dernier des injustes (The Last of the Unjust, 2013) by Claude Lanzmann and also seen at the UKJFF. After watching all 220 minutes of this film with a very quiet, appreciative audience, the question came from my mouth, ‘Why did Lanzmann sit on this [the interview with Benjamin Murmelstein] for forty years? The woman to my right said, ‘He was conflicted’, which was a better explanation than that it would have unbalanced Shoah, (1985) which would, at best, cover a five-year pause. As we, in the UK, have been saturated with WW1 centenary memorials, it’s worth being reminded that another centenary looms - the founding of the Weimar Republic. Telling for me was Murmelstein’s eye-witness testimony that Eichmann was particularly enraged on 9th November 1938 by the anniversary of ‘die jüdische Republik’.

Leviathan (Andrei Zvyagintsev, 2014) worked magnificently at many levels and deserves all the praise that has been given it. I thought Of Horses and Men, (Hross í oss, 2013, Benedikt Erlingsson) delivered everything a good entertainment film should have. Of the many archive screenings, I was particularly captivated by Werner Hochbaum’s Morgen beginnt das Leben (Life Begins Tomorrow, 1933). An excellent example of an inventive early sound film, it revealed a director that for me had been a complete blank.

Julian Ross

In no particular order:

- Vanishing Circuit (Shunsuke Hasegawa, 2014)

- Phantom Nebula (Takashi Makino, 2014)

- Banquet of Love (Haruki Mitani and Michael Lyons, 2014)

- Sound of a Million Insects, Light of a Thousand Stars (Tomonari Nishikawa, 2014)

- Am I dreaming of others, or are others dreaming of me? (Shigeo Arikawa, 2014)

- Double Projection #1 (Meiro Koizumi, 2014)

- Kanagawa University of Fine Arts, Office of Film Research (Yuichiro Sakashita, 2013)

- The Tale of Princess Kaguya (Isao Takahata, 2013)

- Still the Water (Naomi Kawase, 2014)

- Untitled (Human Mask) (Pierre Huyghe, 2014)

Plus two from recent years:

- It has already been ended, before you can see the end (Shigeo Arikawa, 2012)

- The Radiant (The Otolith Group, 2012)

Fires on the Plain

Dimitri Ianni

Being based in France and mostly discovering Japanese films through the festival circuit, I've compiled a list mostly comprised of titles viewed this year and not necessarily based on their Japanese release dates. Here's my top ten in no particular order except for the first two works, which inevitably stand out, both belonging to rare filmmakers. The first one is from Nami Iguchi, director of the remarkable Sex is No Laughing Matter, who after a 5-year hiatus graces us with a new little masterpiece of inventiveness. The Tale of Nishino is a deliciously subtle Lubitschian romantic fable told à la Heaven Can Wait. The careful framing astutely working on symmetricalities, constructed of beautifully elaborate compositions by cinematographer Akihiko Suzuki making full use of depth of field, enhances direction to an elegance and refined state of art rarely seen in Japanese films these days. As for the second, it's the latest and most possibly the last work from veteran and underrated master of comedy Azuma Morisaki after a 9-year silence since Chicken Is Barefoot. Having surprisingly garnered little attention abroad, Pecoross' Mother and Her Days is a touching family tale with a cheerful earthiness that entwines family stories with the "great" history, carefully walking on a tightrope between laughter and tears while avoiding the pitfall of becoming over-dramatic.

In addition, I chose to give a special mention to two documentary works for their radical nature. When most lenses are focusing on Fukushima, news anchor Chie Mikami aims hers at a small village in Okinawa as their inhabitants struggle to oppose the construction of U.S. military helipads. What it lacks in cinematographic value, The Targeted Village makes up for with its undaunted commitment in showing the plight of its people. Despite seldom having been considered seriously, Adult Video (AV) has influenced several contemporary filmmakers, among which Tetsuaki Matsue and Nobuhiro Yamashita. Spoofing the 1981 US classic cross-country road comedy hit, The Sex Cannon Ball Run 2013, The Movie by avant-garde AV director Company Matsuo documents a 1,000-km car race between 6 AV directors from Tokyo to northern Hokkaido. Victory is measured through a counting system involving having sex through telephone dating services (telekura) and performing some of the most incongruous tasks.

Best Japanese Films:

The Tale of Nishino (Nishino Yukihiko no Koi to Boken, dir: Nami Iguchi)

Pecoross' Mother and Her Days (Pekorosu no Haha ni Ai ni Iku, dir: Azuma Morisaki)

Campaign 2 (Senkyo 2, dir: Kazuhiro Soda)

Intimacies (Shinmitsusa, dir: Ryusuke Hamaguchi) 255-min version.

Forma (dir: Ayumi Sakamoto)

The Horses of Fukushima (Matsuri no uma, dir: Yoju Matsubayashi)

There's nothing to be afraid of (Nani mo kowai koto wa nai, dir: Hisashi Saito)

Sweet Whip (Amai Muchi, dir: Takashi Ishii)

Undulant Fever (Umi wo kanjiru toki, dir: Hiroshi Ando)

Bon Lin (Bon to Lin chan, dir: Keiichi Kobayashi)

Atsuko Maeda for her acting performance in the combined Tamako in Moratorium (Moratoriamu Tamako, dir: Nobuhiro Yamashita) and The Seventh Code (Sebunsu Kodo, dir: Kiyoshi Kurosawa)

Special Mentions:

The Targeted Village (Hyoteki no Mura, dir: Chie Mikami)

The Sex Cannon Ball Run 2013, The Movie (Gekijo-ban Terekura Kyanonboru 2013, dir: Company Matsuo)

Best retrospective:

Kinji Fukasaku's full career retrospective at the Cinémathèque Française

The Worst:

The Little House (Chiisai Ouchi, dir: Yoji Yamada)

Fukuchan of Fukufuku Flats

Mark Player

Unlike my last end-of year contribution for the 2012 edition of this feature, I am able to present some favourite films this year. This is partly because I finally made my first pilgrimage to Frankfurt’s Nippon Connection, which was a wonderful experience. If you haven’t been, I strongly recommend it. It’s not overly expensive, the volunteer staff are friendly and considerate, the special guests are often approachable and happy to chat, and it’s very English-friendly (with the exception of the occasional film introduction and the odd lecture).

You also get to see films you probably won’t see anywhere else such as Nagisa Oshima’s rarely screened motion-manga experiment Band of Ninja (Ninja Bugeicho) from 1967 and a retrospective of nine films from the sorely overlooked Ko Nakahira, of which I was able to sample four. Although all four made for interesting viewing, I was particularly tickled by 1966’s The Black Gambler – Devil’s Left Hand (Kuroi Tobakushi – Akuma no Hidarite), the final entry in Nikkatsu’s six-part ‘Gambler’ series starring Akira Kobayashi as an unflappable, James Bond-esque, world-renowned gambler, who often gets caught up in a conspiratorial web of international intrigue, whilst effortlessly wooing a succession of beautiful women in the process. Irreverent and fun, it’s a series that could benefit hugely from receiving box set treatment. It could be a job for Britain’s Arrow Films, who have been putting out a number of cult items from the 1960s/70s of late (I imagine it would look quite good on the shelf next to their recently released Stray Cat Rock collection).

Still on the subject of (re)discovering the work of overlooked directors, the Bradford International Film Festival held the world’s first Yoshitaro Nomura retrospective. Nomura was best known for his film adaptations of stories by popular Japanese crime/mystery writer Seicho Matsumoto; five of which were collected together for this landmark event (and were screened again later on at London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts). I was able to see three of these, including the Hitchcockian missing person thriller Zero Focus (Zero no Shoten, 1961) and the sprawling police procedural The Castle of Sand (Suna no Utsuwa, 1974). As for the third film, The Demon (Kichiku, 1978), I shall go into more detail below.

So below is a list of Japanese films that, while not necessarily the apogee of what’s recently come out, as my viewing has been far from comprehensive, have left a distinctive impression on me nonetheless. A mix of new, very recent and old (but newly screened during the year for one reason or another), I’ve decided to limit my choices to five features for the sake of brevity and quality control. However, some honourable mentions include the absurdly delightful, although slightly flabby, Fuku-chan of FukuFuku Flats (Fukufuku-so no Fukuchan, dir: Yosuke Fujita); the refreshingly brief – if somewhat inconsequential – indie debut, Antonym (Rasen Ginga, dir: Natsuka Kusano); the violent Japanese-Indonesian cat-and-mouse thriller Killers (dir: the Mo Brothers); and the gravity-crossed dystopian anime Patema Inverted (Sakasama no Patema, dir: Yasuhiro Yoshiura).

I’d also like to tentatively mention Shinji Aoyama’s prickly and sometimes uncomfortable Backwater (Tomogui). At least six months have gone by since I saw it and I’m still not sure if I like the film or not – a film with a misogyny-flavoured subject that’s likely to cause debate over whether or not it is indeed misogynistic itself. (For what it’s worth, I don’t think it is. I also think such argument risks missing the point of the film.) Regardless, the fact that I’m still turning it over in my head is commendable in itself, and I found its dour atmosphere of sweltering oppression strangely addictive, thus making it rather difficult to forget.

Anyway, here are my official choices. In no particular order:

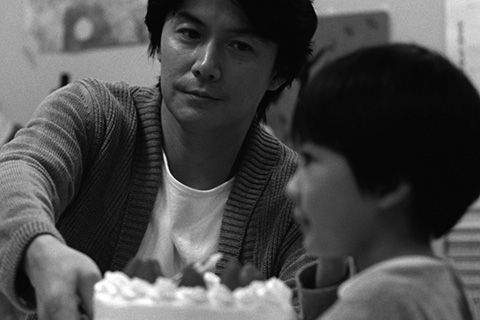

Like Father, Like Son (Soshite Chichi ni Naru, dir: Hirokazu Koreeda)

I actually managed to catch Like Father, Like Son during its limited UK cinema release at the end of 2013. But seeing as it served as the closing film of Nippon Connection, and has continued to make appearances at other festivals, I feel it’s still sufficiently current to talk about. This easily remains my favourite Japanese film of the last few years, and as much as I don’t want to wheel out the usual Koreeda-Ozu comparison, it does feel particularly apt in this case. Not only is this a tender story of nature versus nurture, it’s also a nuanced, humanist drama concerning parents’ devoted connection to their children – even if they are not biologically linked. I think Ozu would have approved.

The Tale of Iya (Iya Monogatari, dir: Tetsuichiro Tsuta)

A sprawling, often lyrical, rural drama that at times feels redolent of Shohei Imamura’s 1983 remake of The Ballad of Narayama (Narayama Bushiko) and at other times of Kaneto Shindo’s The Naked Island (Hadaka no Shima). The Tale of Iya is a rare film-viewing experience with its mouth-watering 35-mm anamorphic cinematography. It’s certainly a refreshing change from the flat, televisual quality of a lot of modern, and often budget-starved, Japanese films. Yes, as others have said in last year’s roundup, the film is overly long at nearly three hours, with the final Tokyo-set stretch seemingly at odds with the first two-thirds. There’s a sequence past the two-hour mark mirroring events right at the film’s start that would’ve perhaps better served as the story’s endpoint. Having said that, the oft-criticised Tokyo segment does build to a goosebump-inducing moment, taking place by one of the inner-city riverbanks, that reminded me that there are some things best left to cinema. Still, if this is anything to go by, I think Tetsuichiro Tsuta could be a master in the making.

Lesson of Evil (Aku no Kyoten, dir: Takashi Miike)

I’m a little late to the party here, but this went down an absolute storm on Nippon Connection’s opening night. Part of the pleasure of this jet black psycho-horror was being part of a full-house crowd that was willing to ride the film’s growing wave of derangement through to its protracted and hyper-violent endgame. Indeed, Lesson of Evil is perhaps Takashi Miike’s most gleefully sadistic outing since 2001’s Ichi the Killer (Koroshiya 1), and if you first boarded the Good Ship Miike back when films like Ichi, Dead or Alive (Dead or Alive: Hanzaisha), Visitor Q and Gozu (Gokudo Kyofu Daigekijo: Gozu) weren’t so much pushing the envelope but mercilessly tearing it to shreds, then this is for you.

The Demon (Kichiku, dir: Yoshitaro Nomura)

I was so impressed with The Demon that I wanted to include it here. It was, for me, perhaps the most stomach-churning and gripping of Nomura’s Matsumoto adaptations. With a story concerning a struggling business owner – and his wife – being saddled with his three illegitimate love children after his long-time mistress decides to skip town, The Demon goes places that films nowadays would not have the resolve to pursue. Struggling to care for children that are not her own, Shima Iwashita’s embittered wife bends Ken Ogata’s two-timing husband into getting rid of these extra mouths in a way that won’t draw suspicion. In a similar vein to Peter Lorre’s sympathetic child killer in Fritz Lang’s M, Ogata gives possibly the finest performance of his career; one where you feel the full weight of his dilemma, complicated by his increasing attachment to his estranged offspring. The greatest trick that The Demon manages to pull is convincing you to care about an absolute scoundrel. It’s not an easy watch, but I still recommend it highly.

Woman of the Dunes (Suna no Onna, dir: Hiroshi Teshigahara)

Another oldie, except this time a better known classic that, I’m embarrassed to say, I only saw for the first time during 2014. I feel it relevant to select this over something more current because Teshigahara’s 1964 landmark masterpiece – concerning an entomologist getting caught in an almost Kafkaesque situation of being forced to live with a widow trapped at the bottom of a steep sand dune – celebrated its 50th anniversary in 2014 with surprisingly little fanfare (not even a shiny, remastered Blu-ray release from what I can tell; although there was a screening or two, hence its inclusion here). Based on Kobo Abe’s book (he wrote the screenplay as well) and featuring a spine-tingling, experimental score from composer legend Toru Takemitsu, Woman of the Dunes now ranks as one of my all time favourites to the point where I’m kicking myself for not getting around to watching it sooner.

Ninja Theory (Ninja Seori, dir: Takashi Iitsuka) + The Portrait Studio (Shashinkan, dir: Takashi Nakamura)

Finally, I thought it would be nice to give a shout out to a couple of Nippon Connection’s supporting short films that, for my money, roundly upstaged their respective main attractions. Takashi Iitsuka’s charmingly shambolic, homemade mini opus Ninja Theory may very well be the greatest short film featuring ninja action figures/puppets ever made. And by homemade, I mean that the whole thing was shot on appropriately scaled-down sets in the director’s back garden (with the support of the Yubari Fantastic Film Festival). The bookending “Beginning” subtitle suggests this may be part of a series of other micro adventures. I hope that will be the case.

On the other hand, Takashi Nakamura’s gorgeous animation The Portrait Studio was a very different experience. An exquisitely rendered story of a Meiji-era portrait photographer trying to coax a smile from a particularly stubborn customer over several decades, with the gradual modernisation of Japan acting as a breath-taking backdrop, The Portrait Studio is both consummately elegant and achingly nostalgic. It’s possibly the finest 17 minutes I’ve had in a cinema this year and I’d be lying if I said it didn’t make me well up.

The Tale of Iya

Eija Niskanen

For some reason most films listed below have a strong female angle, with Ando and Oshima leading the young actress chart, while Rie Miyazawa makes a delightful comeback. Hope to get more female-audience oriented films in Japan in the future!

When Marnie Was There (Omoide no Marnie, dir: Hiromasa Yonebayashi)

Under-appreciated little gem from Studio Ghibli, a special treat for female audiences, in the narrative mode of classic girls’ novels.

Tokyo Tribe (Dir: Sion Sono)

Rap musical covering all our favorite hoods in Tokyo. Sometani Shota marvels as a rapping narrator in this film that shows the director’s sure-handed understanding the musical as a film genre.

100 Yen Love (100 En no Koi, dir: Masaharu Take)

Sakura Ando does method acting and how! A lot of young starlets could do with a few acting lessons from Ando.

Paper Moon (Kami no Tsuki, dir: Daihachi Yoshida)

Rie Miyazawa takes on an interesting role in this noir-influenced story of bank embezzlement and sexuality merging together.

Ecotherapy Getaway (Dir: Shuichi Okita)

Not a big film, but nicely executed and finally obasans get a more nuanced treatment than just being the target of ridicule.

Fukuchan of Fukufuku Flats (Fukufukuso no Fukuchan, dir: Yosuke Fujita)

Miyuki Oshima stars in the main male role with such skills that the film escapes any easy laughs.

Best non-Japanese films:

Birdman (Dir: Alejandro Inarritu)

Film, genres, theater, stardom. Few films tackle these issues in one film and with such an interesting shooting/editing style.

Boyhood (Dir: Richard Linklater)

So absorbing that I could easily have watched more of it.

Big Hero 6 (Dirs: Don Hall and Chris Williams)

Disney animators show their anime influences in a fun and colourful animation with the Totoro-like Baymax as the emotional centre.

They Have Escaped (He ovat paenneet, dir: J-P Valkeapää)

Best Finnish film of 2014. What begins as a generic rebellious youth/road movie, but ends up as a hallucinatory Hansel and Gretel with disturbingly violent images.