Intergalactic Tokusatsu: Charting The Japanese Space Opera, Part 1

- published

- 21 March 2014

Wars in distant galaxies. Explorations of hostile worlds. Alien visitors bringing mankind messages urging for peace and co-operation, or campaigns of mass destruction. Averting inter-planetary disasters, and scientific conquest of the known universe: the Japanese space opera sub-genre, films in which space travel and the depiction of alien worlds play an important role in the narrative, has been a cornerstone iconography of the nation's science fiction cinema since its very beginnings.

The Mysterians

However, such films are often mooted in a manner of film production whose content is often dismissed for its apparent campy silliness, ropey models and sets, and ridiculous costumes. An opinion that is frequently re-enforced by insensitive English dubbing when such films are released internationally. As a result, much of its output is either critically derided, languishing in obscurity, or overshadowed by more famous or popular creations within the same production model.

This writing serves to explore the evolution of the space opera and how, despite its progressively sullied reputation, it has remained profoundly influential and endearing within Japanese science fiction cinema, television and anime. And how it has been pioneering in terms of paving the way for vital distribution channels to Western markets, stressing the increasingly intertextual relationship between Japanese and American film companies. It is a voyage of re-discovery that begins at the advent of tokusatsu cinema in the mid 1950s.

Blasting Off: Tokusatsu, Godzilla and discovering the international audience

Literally meaning "special filming", tokusatsu is a term used to define any Japanese genre film that requires heavy amounts of special-effects photography, optical tricks, miniature model work, or suitmation – where actors don costumes to assume the role of giant, non-human creatures. The most well known of these were the seemingly never-ending wave of monster movies – kaiju eiga – that many of the Japanese film studios rolled out in a production-line mentality during the 1950s and 60s; predominantly by Toho, but others quickly joined the game when they saw the lucrative financial rewards to be had. The first kaiju film, and progenitor of tokusatsu, is also the most famous: Ishiro Honda's original Godzilla (1954), where the titular giant lizard – awoken as a result of nearby nuclear testing – goes on an irate rampage through post-war Tokyo.

Although Godzilla, contrary to popular belief, was not the first Japanese science fiction film – that honour instead goes to Shinsei Adachi's The Transparent Man (Tomei Ningen Arawaru, 1949), produced by Daiei [ 1 ] – it was the first (and some would argue only) film of its kind to matter. This rationale can be explained twofold. First, it was one of the first major Japanese film productions to be openly critical about the use of atomic power, something that had been suppressed during the preceding U.S. occupation after the Second World War. Initially inspired by a scandal involving a fishing vessel and her crew being radioactively contaminated after a miscalculated U.S. hydrogen bomb test conducted on Bikini Atoll [ 2 ], not to mention the cataclysmic disaster inflicted upon Hiroshima and Nagasaki less than a decade before, Godzilla has since become a national symbol for abused atomic power and a global pop-culture icon to boot. Many other tokusatsu films, especially those directed by Honda, would incorporate anti-atomic sentiments in their storylines.

Secondly, Godzilla mattered because it represented the first Japanese film that could be exported to the West for the purposes of mass consumption. Particularly for those who hadn't had the opportunity, wherewithal, or inclination to see Akira Kurosawa's decidedly higher-brow Rashomon win the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival in 1951 (or the subsequent festival favourites of Kenji Mizoguchi). In this regard, Ishiro Honda was very much ahead of his time. He mastered the art of mass-destruction cinema decades before Hollywood discovered CGI. Honda's original Godzilla featured plenty of polemic post-war spectacle that was not only socially conscious but could be enjoyed by and, perhaps more importantly, marketed to other countries.

Given the Americanisation treatment, Godzilla was reworked and released as Godzilla, King of the Monsters! (1956), complete with newly written and shot segments that featured an American journalist (played by Raymond Burr) reporting on the monster's carnage for increased compatibility, and to possibly go some way to fool certain viewers over the production's true origin. It also downplayed the anti-atomic angle, but yet the sense of a seemingly new and exotic cultural paradigm remained, giving ordinary but curious westerners the opportunity to sample the relative mysteries of the East without straying too far from their comfort zone.

Many tokusatsu films would get similar treatment over the ensuing decades to varying degrees. Some would just have their dialogue dubbed into English to form an international release, others would have scenes dropped, rearranged or re-shot at the behest of Western distributors. At any rate, it gave Japanese films a platform to appeal to mass audiences beyond its borders (predominantly via television).

A sequel directed by Motoyoshi Oda, Godzilla's Counterattack, aka Godzilla Raids Again (Gojira no Gyakushu, 1955), was quickly put into production and Japan's most successful and longest-running film franchise was born, with Toho spawning 26 more instalments over the next five decades. As Godzilla's Counterattack proved to be as popular as its antecedent, other studios felt it best to follow Toho's lead.

One Small Step for Daiei: Warning From Space

Rather than creating their own competing giant monster franchise – although they eventually did just that with Gamera (1965) – Daiei took a different approach and found inspiration in the night sky. Originally titled Spacemen Appear In Tokyo, before it was re-christened upon being finally sold to U.S. television in the mid-1960s [ 3 ], Warning From Space, a.k.a. Mysterious Satellite (Uchujin Tokyo ni Arawaru, 1956) was made with an international audience in mind from the outset. Thus, it feels redolent of much of the space-centric cinema being produced in the U.S. at the time, in particular the work of Hungarian-born Hollywood producer George Pal.

Originally an animator, before emigrating to America after National Socialism came to power in Germany, Pal was the man behind several key Hollywood science fiction films throughout the 1950s, including: Destination Moon (1950) and The War of the Worlds (1953), the first film adaptation of H.G. Wells's classic novel. However, Warning From Space is perhaps most indebted to the Pal production When Worlds Collide (1951), based on Philip Gordon Wylie and Edwin Balmer's 1933 novel about a recently discovered star on a collision course with Earth. It also follows a template similar to that of another U.S. science fiction classic from that year: Robert Wise's The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951), in which an alien ambassador, adopting human form, travels to Earth to warn its world leaders about potential self-destruction in light of the then ongoing nuclear arms race.

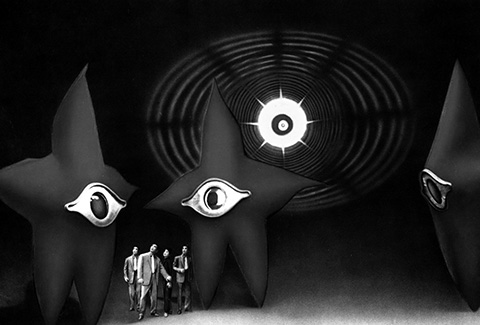

Warning From Space

In Warning From Space, an alien race from the planet Paira plans to warn humankind of an impending apocalyptic catastrophe. With the appearance of dark starfish of a similar physical scale to humans, with a large eye at their centre, their first attempt to reach intended contact Dr. Komura (Bontaro Miake) proves unsuccessful. They unintentionally terrify many unsuspecting Japanese, who see the creatures land in various places around Tokyo. Acquiring a photograph of Hikari Aozora (Toyomi Karita), a popular entertainer, one of the aliens – Ginko – volunteers to undergo "transmutation", thereby assuming the form of Aozora (based on her picture). Ginko, Aozora's alien doppelgänger, soon infiltrates Dr. Komura's circle of astronomers. She seizes the formula of one of his colleagues – Dr. Matsuda (Isao Yamagata) – for a hypothetical, high-energy substance called Urium 101 that is considerably more powerful than any atomic or hydrogen bomb. Ginko warns of the effects such a powerful device would have should it be manufactured. She soon reveals herself to be a Pairan and explains to the scientists that a rogue planet, designated "Planet R", is on a collision course with Earth. But because Earth and the alien home world share the same orbit at opposite sides of the sun, mankind's destruction will yield dire consequences for their planet also. Komura and his fellow scientists work with the Pairans to avert the disaster.

Warning From Space was the first Japanese science fiction film to be produced in colour, a fact that regularly appeared on the marketing when it was released. It could be seen as a show of one-upmanship on Daiei's part. After all, Toho's Godzilla films, which had soundly upstaged the former studio's epochal The Transparent Man, were both shot in monochrome. It's a point made all too clear in the scene that leads to the discovery of the newly transformed Ginko. Toru (Keizo Kawasaki), who works with his father and Dr. Komura at the observatory, is out rowing on a lake with his girlfriend. She marvels at the surrounding picturesque landscape, exclaiming (in the English-dubbed version): "Beautiful, isn't it? Look at that mountain; all that colour!"

Something that Warning From Space does have in common with Godzilla, however, is the central theme of atomic weapons. But where Godzilla was very clear and succinct in its indictment, Warning From Space delivers somewhat of a mixed message, though it ultimately argues that nuclear power can be used for good if placed in the right hands. Ginko warns against the development of Urium 101, a substance which her planet had discovered years previously and discarded for fear of its power, only then to be complicit in its use against Planet R after a volley of regular atomic weapons launched at the looming object of armageddon does nothing to stop it. It's a decision perhaps made for dramatic purposes rather than for ethics or logic, as is the case later on when Matsuda is kidnapped by men intent on getting his Urium formula to sell on to interested parties. Ginko has the ability to locate and rescue Matsuda via a discrete communication device that was given to him, something that neither the scientists or the audience are aware of. She waits until what feels like the last moment to share this information and act upon it.

Nevertheless, Warning From Space was an important first step for the Japanese space opera, even though there were only a total of three scenes set in space, all of which are aboard the Pairan spaceship. The craft adopts an exterior design similar to that of a civil defence siren, with klaxon-esque funnels pointing out into space in a circular arrangement like a celestial early-warning system. An appropriate symbol.

Although it didn't have anywhere near the budget of the first Godzilla, Warning From Space boasts a certain ingenuity that is often overshadowed by its frequent use of cliché, questionable storytelling decisions and the somewhat daft appearance of its asteroidean alien creatures. It has been noted that they 'look like nothing more than people trapped in giant pillowcases' [ 4 ]. Perhaps the most impressive feat is the transmutation sequence, where director Koji Shima depicts the transition from Pairan to human in staccato-like fashion, marrying various individual stages of the metamorphosis with an extended sequence of cross dissolves. Colour also plays an important role; so important, in fact, that the studio drafted famous avant-garde artist Taro Okamoto to serve as “Color Designer” [ 5 ]. As Planet R nears, the Earth's atmosphere heats up to dangerous levels. The heat is emphasised with a strong and pervasive orange/red tint, creating a bold and effective mise-en-scène that would obviously not be achievable in monochrome.

As a result, Warning From Space has become somewhat of an unwitting innovator. Its legacy was secured when it was revealed, along with other Japanese tokusatsu films, to be a potential influence on Stanley Kubrick when making his landmark science fiction opus 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). In Stanley Kubrick: A Biography, John Baxter notes how the 'technical assurance' of many kaiju and tokusatsu productions, including Warning From Space, led to them being snapped up and resold by Hollywood [ 6 ]. It would also have a strong influence on the next wave of Japanese space films.

One Giant Leap for Toho: The 'Space Opera Trilogy'

After Warning From Space, Toho was quick to react and produced three films over a five-year period that have since been referred to as the studio's "Space Opera Trilogy," consisting of The Mysterians (Chikyu Boeigun, 1957), Battle in Outer Space (Uchu Daisenso, 1959) and Gorath (Yosei Gorasu, 1962). All three films were directed by Toho's go-to tokusatsu helmer Ishiro Honda, with regular collaborator Eiji Tsuburaya overseeing the special effects sequences. Known as Japan's "Father of Special Effects," Tsuburaya was a mentor and a tremendous influence on the outcome of Honda's work. The director openly admitted this in an essay he wrote entitled 'Tsuburaya, Magician of Special Effects' in response to his colleague's death in 1970 [ 7 ].

Another notable commonality is that the stories for this loose trilogy were all devised by the same man: Jojiro Okami, a mystery writer and former aeronautical engineer/test pilot for the Japan Self Defence Force (JSDF). Screenwriting duties fell to Takashi Kimura (The Mysterians and Gorath) and Shinichi Sekizawa (Battle in Outer Space), who have written almost all of Honda's fantasy/science fiction film scripts between them. Considering Okami's background, it comes as no surprise that all these entries focus on the Earth being defended; either from alien invaders (The Mysterians and Battle in Outer Space), or a wayward star that threatens to collide with the planet (Gorath).

The Mysterians

In The Mysterians, the titular alien race has, intriguingly, already infiltrated the Earth by hiding their huge base of operations underground near Mount Fuji (how they've managed to do this exactly is never really explained). Their planet has been ravaged by nuclear war and they seek asylum on Earth, requesting a tract of land 3 kilometres in radius and, much to the chagrin of the leaders of the world, the right to marry Earth women. The wars on their home world have left the majority of the Mysterian population genetically mutated and they believe that cross-breeding with human females will ultimately revive their corrupted and moribund gene pool.

However, their desires for peace are a put-on as the alien refugees intend to claim the entirety of Earth as their own, and have even started kidnapping Japanese women after causing an earthquake that destroys a nearby village, which opens the film. They have also unleashed Moguera, a large battle robot, as a "demonstration of their power" even though such a demonstration runs contrary to their intentions for civility and diplomacy. It also runs contrary to Honda's original vision for the project, as he, at the time, was trying to escape from the shadows of giant monsters. However, Toho producer Tomoyuki Tanaka wanted to shoehorn in a kaiju to help secure international sales. After the success of Godzilla, King of the Monsters! in the U.S. just that previous year, he was all too keen to capitalise on this new market. This would also explain why the majority of The Mysterians consists of little more than a series of battles between the alien invaders and the Earth Defence Force (the literal English translation of the film's original Japanese title). The latter being a utopian, international peacekeeping initiative – no doubt inspired by Okami's stint in the JSDF – that also makes an appearance in Battle in Outer Space.

As such, there is a strong sense of world community and international co-operation in the film. The Japanese flag flying proudly next to those of other nations is a particularly poignant image as Japan had only just recently joined the United Nations that previous year. It was the first step towards reconciliation with the international community after the chaos of the war, later crystallised by Japan's hosting of the 1964 Olympic games. This new idealism is further developed in the two subsequent films of the trilogy, with the UN and co-ordination between its members becoming an increasingly key component of their narratives.

Battle in Outer Space depicts an international conference held at Tokyo's Space Research Centre after a series of bizarre and cataclysmic events take place. A newly built space station is destroyed by flying saucers; Venice is flooded by a seemingly random surge of water; and a railway bridge is lifted into the air, via an alien tractor beam, causing a train to derail and plummet into a ravine. When it is discovered that there are strange radio signals emanating from the Moon, an expedition consisting of two recon shuttles is launched. One is lead by Japanese scientist Dr. Adachi (Minoru Takada), the other by an American, Dr. Richardson (Len Stanford). It's an arrangement that's reflective of Japan's new enthusiasm for international involvement as well as its desire to make amends with America; a radically different stance to the lamentations and thinly veiled contempt as evidenced in Godzilla just five years previously. On a more mercenary note, the inclusion of Caucasian characters would help make the film more palatable to Western markets.

Battle in Outer Space is also notable for placing a strong emphasis on space travel, with the bulk of its narrative based around the expedition and exploration of the Moon. We were only treated to a handful of scenes set aboard the Pairan space craft in Warning From Space, and The Mysterians featured no scenes in space whatsoever (thereby not really qualifying it as a space opera despite being part of a trilogy branded as such). The latter perhaps frustrated Tsuburaya, whose desire of wanting to explore beyond the scope of the Earth was strongly hinted during the publicity for another Honda collaboration, Varan the Unbelievable (Daikaiju Baran, 1958). In Mushroom Clouds and Mushroom Men: The Fantastic Cinema of Ishiro Honda, Peter H. Brothers points out that 'Tsuburaya wrote: "The Dark Side of the Moon is still a mystery and I would really like to make a film on that subject. However the United States and Soviet Union are doing a lot of research in this area, and if their Moon rockets get to the Moon and show us what is there through televised broadcast, then we will know everything. Therefore, we must create it before it happens"'[ 8 ].

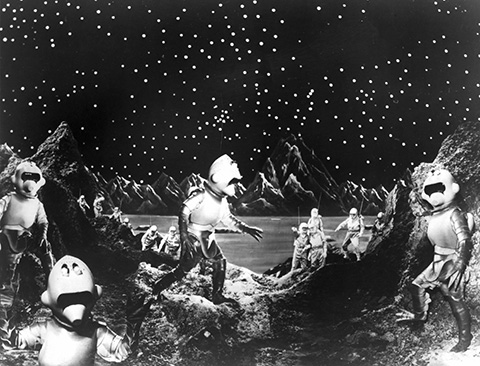

Battle In Outer Space

With this thirst for exploring the unexplored, the interplanetary scope gives the film a sense of scale and grandeur not present in previous Japanese science-fiction cinema. But with this ambition comes certain naiveties. Like many science fiction films of the era, Battle in Outer Space suffers from numerous groundless predictions with regards to space travel that have since become dated and cliché; most notably the effects of rapid acceleration during blast off [ 9 ]. The film's handling of low gravity is also inconsistent. Most characters don't seem to be too bothered by it and carry on unimpeded, whereas one crew member floats off on two separate occasions, unable to adjust, even though there seems to be little to adjust to. However, the sets, particularly aboard the shuttle and the lunar surface, still retain a certain credibility about them and remain impressive for the era. The space suits are a realistic silver, with Honda eschewing the baggy, colourful modernism of Pal's Destination Moon – perhaps the film's biggest design influence. Interestingly, the space suits seen later in Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey are of mix of these two films: the various colours of Destination Moon combined with the more streamlined, tactile design of those found in Battle in Outer Space.

But despite this predominant space setting, Battle in Outer Space is ostensibly a reworking of Okami's storyline for The Mysterians, only this time the alien race appear to be a little more on the ball. Rather than claiming for peace then unleashing a giant murderous robot, or asking permission to breed with Earth-women only to start kidnapping them anyway, the Natal have developed a mind control technology that helps them undermine the strength of their human opponents. First, they take control of a delegate at the science conference and try to sabotage the demonstration of an experimental yet very powerful heat ray that could be used against the alien invaders to great effect. Later, they possess Iwomura (Yoshio Tsuchiya), one of the crew for Adachi's spacecraft, who sets about sabotaging the mission by trying to destroy the two ships after they've landed on the lunar surface – succeeding with one of them. Iwomura importantly gives the alien enemy a face (albeit a human one) that's not obscured by a tinted helmet, as is otherwise the case both here and in The Mysterians. Battle in Outer Space, then, is not only the most visually interesting of the trilogy, but arguably the most engaging from a narrative standpoint.

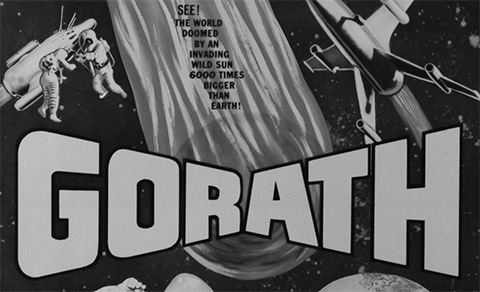

And if Battle in Outer Space is a retread of The Mysterians, then Gorath is most definitely a retread of Pal's When Worlds Collide (and to a lesser extent Warning From Space). The titular menace is a runaway star making a beeline towards Earth and the world's leading scientists have to work together to solve the crisis. Upon realising that Gorath cannot be destroyed, doctors Konno (Ken Uehara), Tazawa (Ryo Ikebe) and Sonoda (Takashi Shimura) devise a way to construct huge thruster jets at the South Pole to push the Earth out of the star's way, re-adjusting its orbit. It's certainly a more optimistic (although hugely far-fetched) scenario than the one presented in Pal's When Worlds Collide. The solution in that film is to construct a spaceship that will transport a comparative handful of the world's population to a recently discovered planet that is able to support carbon-based life, ensuring the human race's survival. However, the rest of mankind is left behind on Earth for the inevitable impact.

Once again, Gorath builds and improves on the themes that permeated throughout its two predecessors and stands as one of Honda and Tsuburaya's finer works outside Godzilla. The scale has once again increased, creating a global disaster story that feels international – interplanetary in fact – despite a budget that would have been reasonably modest compared to its Hollywood contemporaries. The film starts with a manned spacecraft monitoring the star, which has over six thousand times the mass of Earth but is only half the size. The craft gets caught in Gorath's gravitational pull, with the crew unable to escape with their lives. However they are able to send important data about the star back to colleagues on Earth.

The depiction of space shuttle technology has greatly improved since Battle in Outer Space, and details such as gravity conditions seem at least consistent if not realistic. The shuttle interiors feel far more authentic than anything produced thus far, especially the low-budget science fiction serials that studios had begun to produce for both theatrical and televisual exhibition (more on these in a moment). The exterior scenes of craft flying though space, with a nicely detailed Earth fixed in the background, lend these sequences a grandeur that hadn't been achieved before and hold up favourably to the epochal counterpart sequences of A Space Odyssey when it came out half a decade later.

Just as impressive is the base at the South Pole, where Earth's scientists build the giant thrusters that will move the planet out of harm's way. It has to be Tsuburaya's finest hour for the complexity and sheer duration of the initial sequence. We see numerous ships breaking through the ice and docking, bulldozers levelling the ground, trucks and helicopters carrying building materials, plus the construction of the site itself. It certainly gives the film an epic scope and remains commendable after half a century, even though they are blatantly models.

Gorath

But what makes Gorath different from all the other big-screen disaster dramas of its era is a distinct lack of hysteria. Upon hearing the news that the Earth will soon be destroyed, ordinary Japanese citizens either accept it as an act of fatalism or are fairly indifferent on the subject, choosing to continue as before – a holdover from former wartime mentality perhaps. When the crew of the Hawk (the shuttle that observes the star at the start) are unable to escape from the gravitational pull, they dutifully continue to gather data until the bitter end, knowing that their final minutes will be of greater benefit to their colleagues if they remain productive. It's a moment of disarming pathos that Honda was occasionally capable of issuing amongst all the perceived silliness of miniatures and men in suits. It was a skill of his that is often overlooked.

Given its more serious approach, it comes as little surprise that the only time Gorath really lets itself down is with the inclusion of Maguma, another regrettable example of kaiju shoehorning – again at the insistence of Toho producer Tanaka. But unlike the battle robot of The Mysterians, which was at least palatable if a little unnecessary and counterintuitive, the creature in this film is a large, flailing walrus-like monstrosity, hibernating beneath the ice. Its presence is baffling to say the least, even though Shimura's Dr. Sonoda deduces that the thrusters warming the South Pole may have freed it (a rather prescient environmental message in hindsight). Nevertheless, Maguma begins to frolic about angrily; its tantrum demolishes part of the base and delays Earth's slow manoeuvring from Gorath's trajectory, but not by much. Its inclusion feels all the more token when Sonoda and his scientist friends are able to dispatch the beast with a couple of expert laser beam shots from their circling jet plane.

As a result, Maguma's screen time only amounts to a few minutes, which were promptly excised by U.S. distributors after a preview screening elicited laughter from the audience. They dubbed the comical creature "Wally the Walrus" [ 10 ]. Indeed, the opinions of American distributors and test audiences would become more influential as the tokusatsu boom progressed throughout the 1960s. With demand seemingly far greater than supply, distributors needed to come up with new ways to keep the market sufficiently quenched.

Syndicated Transmissions: The Re-packaged Adventures of Starman, the Prince of Space, Johnny Sokko and his Flying Robot

When it came to exporting tokusatsu to U.S. television, it wasn't just films that were up for grabs. By the early 1960s, it started to become common for Japanese theatrical serials and television series to be sold as well. However, rather than porting over a show's entire back catalogue, American distribution companies felt it best to re-edit and merge episodes into one or several feature-length products that were often tailored to fit a 90 minute television slot [ 11 ].

The most famous example of this process perhaps lies with Shintoho's Super Giant, a theatrical series of short tokusatsu features comprised of nine 40-60 minute instalments intended for double (sometimes triple) bills with other studio releases. Typically, a new episode would be released into theatres every couple of months, starting in the summer of 1957 through to the spring of 1959. The first six instalments were directed by "The King of Cult" Teruo Ishii, who was then at the start of his career.

The titular hero of the series (played by Ken Utsui), rather than a giant, is ostensibly Japan's answer to famous pop-culture icon Superman. Like Superman, Super Giant is an alien of human appearance and is virtually indestructible. Other powers, given to him by the Globemeter that he wears on his wrist, grant him the ability to fly, to detect radiation and to speak and understand any language (he can also change costume instantaneously). He was created by the Peace Council from the Emerald Planet with the objective of bringing harmony to the universe.

Super Giant

The Super Giant series was purchased by Walter Manley Enterprises in the early 1960s and was subsequently re-edited into four TV movies that were released in 1964. The first three films – Atomic Rulers (made from episodes 1 and 2), Invaders from Space (3 and 4) and Attack from Space (5 and 6) were surprisingly coherent due to plotlines from the original serial having a two-part story arc, often ending the first on a cliffhanger. The fourth film, Evil Brain from Outer Space, was made up from episodes 7, 8 and 9, which operate as standalone stories, and therefore didn't make much sense when edited together, as over half of the combined footage was culled from the final cut [ 12 ].

Super Giant had his name changed to Starman for all four films. Atomic Rulers sees the newly re-christened superhero dispatched to Earth by the Peace Council to thwart a terrorist group from the fictional country of Meropol, who are planning to decimate the world with nuclear weapons. In Invaders from Space, Starman faces off against a race of reptile-like aliens intent on changing the Earth's orbit. Likewise, Attack From Space pits him against another hostile alien invasion – a Nazi-esque enemy army from the Sapphire Galaxy. And finally, Evil Brain from Outer Space sees Starman incoherently take on the evil genius Balazar and his followers.

Walter Manley Enterprises had also purchased Planet Prince (1958-59), a TV series produced by Toei in an attempt to replicate the same success the Super Giant series was enjoying at the time. Toei also released two theatrical films – Planet Prince (Yusei Oji) and Planet Prince: The Terrifying Spaceship (Yusei Oji – Kyofu no Uchusen, both 1959) – that were essentially a boiled boiled-down remake of the series. A different actor played the titular hero and the costume, which bore a strong resemblance to Super Giants's cape and spandex outfit, was also altered. It is from these two films that Walter Manley's U.S. TV movie The Prince of Space (1959) was assembled, which sees an alien invasion of Earth scuppered when the hero, a galactic peacekeeper of sorts, arrives to intercept the attack. He then pursues the invaders, the Krankorians, in his flying saucer, which leads to further skirmishes. Toei would later rework this premise to make a legitimate cinema release, Invasion of the Neptune Men (Uchu Kaisokusen, 1961), which features a very young Sonny Chiba in one of his first leading roles as the hero Iron Sharp (or Space Chief in the subsequent, and by this point inevitable, U.S. version – also courtesy of Walter Manley Enterprises).

This trend of making films out of TV episodes continued into the 60s thanks to the popularity of emerging tokusatsu sub-genres such as the kyodai (giant) hero format, including TV series such as the highly influential Ultra Q (1966) and its follow-up Ultraman (1966-67). Both of these were produced by Eiji Tsuburaya's newly formed production company Tsuburaya Productions and spawned many imitators. One of which, Toei's Giant Robo (1967-68), later syndicated to U.S. television as Johnny Sokko and his Flying Robot, was also given the re-edited feature-length treatment. American International Pictures, the distributor of many Westernised versions of tokusatsu productions, cobbled together a bunch of episodes from the show to make a feature-length effort entitled Voyage Into Space (1970).

Giant Robo

However the title is a total misnomer as there is no such voyage, with the events of the film mainly taking place on Earth. The story, stringed together from four episodes of the series, consists of the repeated attempts of an interstellar terrorist group, the Gargoyle Gang, to conquer the Earth. They are, however, continually thwarted by Johnny Sokko, a ten-year old boy who is in control of a 100-foot tall fighting robot, armed with energy beams that shoot from its eyes and missiles that fire from its finger tips (among other weapons). Johnny's ability to control the robot, via a wrist communicator, earns him a place at Unicorn, a secret peacekeeping initiative. But aside from the Gargoylian flying saucer approaching the Earth, entering the atmosphere and continuing into the depths of the Pacific Ocean at the film's start, there is none of the space travel that the title promises. It may have been a ploy by AIP to capitalise on the global interest in space travel, which, in the years during NASA's six manned missions to the Moon between 1969 and 1972, was at fever pitch [ 13 ].

But there was a problem with this phenomenon of re-editing episodes of these series and selling them on as feature films: most of them simply didn't have the budget or production values that legitimate, competing features wielded. They were, after all, intended for small television screens. Unaware of these humble origins, Western viewers naturally assumed that these productions (that had often been crudely bodged together to capitalise on trends, or simply just to make a quick sale) were genuine Japanese cinema imports.

As such, many of these films have become the target for ridicule over the years. Cult U.S. television comedy series Mystery Science Theatre 3000 (1988-99) often picked on many of these pseudo-films. The show's format consists of a man (originally played by Joel Hodgson, then later by Michael J. Nelson) and a contingent of robot sidekicks being subjected to watching an awful B-movie each episode as part of an involuntary psychological experiment taking place on an isolated space station. Joel/Mike and the robots maintain their sanity by making audible wisecracks and heckles aimed at the film and its flaws for comedic purposes (termed as "riffing"). The Prince of Space was the subject of one episode in the eighth season, as was Invasion of the Neptune Men.

Despite the ridicule, Mystery Science Theatre 3000 and its long-standing cult audience have arguably helped secure a niche following for these films, which may have otherwise been lost in the increasing malaise of low-budget, straight-to-TV movies. It comes as no surprise that aficionados of vintage, so-bad-it's-good cinema such as Ed Wood's Plan 9 From Outer Space (1959) would find these pseudo-films from Japan strangely appealing.

Naturally, not everyone has taken kindly to this televised exercise in schadenfreude. Sandy Frank, the producer behind the U.S. versions of the Fugitive Alien and Gamera films, was outraged by the show's mockery of not just the films, but of him personally [ 14 ]. And Stuart Galbraith IV has referred to MST3K as 'wrong-headed and contemptible,' also citing that the process of making feature-length compilations from these cheap TV series in the first place as having 'seriously wounded the already poor image of Japanese fantastic cinema most Americans [had]' [ 15 ]. However, television, it seemed, was killing the industry in more ways than one.

Lost in Space: Gamera and Godzilla

As television's encroachment on the entertainment landscape caused box office returns to steadily decline throughout the 1960s, many kaiju films started incorporating space travel and aliens into the their narratives as a means of keeping the genre fresh and interesting for viewers. With its jet thruster-like topology, achieved by retracting its legs and tail into its shell, Daiei's Gamera often had adventures in space. Most notably in 1969's Gamera vs. Guiron (Gamera tai Daiakuju Giron), better known in the U.S. as Attack of the Monsters, the fifth film in the original Showa-era series.

Gamera vs. Guiron sees two children – Akio and Tom, an American – sneak aboard an unoccupied flying saucer that has landed nearby. However, the vessel takes off without warning and embarks on a predetermined flight back to Terra, an alien planet that orbits the sun in direct opposition to the Earth (like Paira in Warning From Space). Despite its capability for mass destruction, Gamera has an affinity towards children and, sensing their plight, follows them to Terra in an attempt to rescue them. There, Gamera is pitted against Gurion, a strange knife-headed lizard that defends the alien city and its two remaining inhabitants from the Space Gyaos: a race of Pterosaurs-like creatures.

Deep space proved to be a recurring element throughout the series. At the end of 1965's original Gamera, the monster is imprisoned in a rocket ship and banished to Mars. The first sequel, Gamera vs. Barugon (Daikaiju Ketto: Gamera tai Barugon, 1966), starts with a meteorite colliding with said rocket ship, releasing Gamera, who promptly returns to Earth for another round of causing chaos. In the fourth film, Gamera vs. Viras (Gamera tai Uchu Kaiju Bairasu, 1968), Gamera intercepts a hostile flying saucer that intends on attacking the Earth. And at the start of the seventh film, Gamera vs. Zigra (Gamera tai Shinkai Kaiju Jigura, 1971), aliens assault a Japanese moon base.

Gamera vs. Barugon

And let's not forget Godzilla, who also embarked on some intergalactic antics of his own. The Great Monster War, aka The Invasion of Astro-Monster or Monster Zero (Kaiju Daisenso, 1965), involves Japanese and America astronauts discovering a new world called Planet X, populated by an alien race called the Xians. The Controller of Planet X asks mankind to capture and bring them the kaiju Godzilla and Rodan to help them fight Monster Zero [ 16 ], which has been terrorising their home world and has forced their people underground. Mankind complies, presenting the Xians with both creatures. However, the whole thing is a ruse and the Xians use all three monsters to attack the Earth, controlling them using magnetic waves.

By the end of the 60s, the formula showed signs of stagnation as the industry continued to repeat itself. The X From Outer Space (Uchu Daikaiju Girara, 1967) starts with scientists going on a space mission to Mars to investigate reports of UFO activity. Approaching the planet, the crew come into contact with an alien craft that contaminates them with spores. Returning to earth with the spores, one sample mutates into a giant, insect-poultry-lizard thing – referred to as Guilala – which wreaks havoc upon Tokyo. It was the first attempt by Shochiku to produce a film of this style and seems an unusual decision considering the powers that be had pointedly resisted jumping on the science-fiction/fantasy bandwagon in the past. The studio was best known for its gendai-geki (contemporary dramas), producing many of Yasujiro Ozu's most famous films. However, Ozu's death in 1963, coupled with the studio's then financially precarious position were possible factors for their short-lived dalliance in tokusatsu production, which only lasted for three more films of varying themes [ 17 ].

Likewise, the first reel of Ishiro Honda's Space Amoeba, aka Yog: Monster From Space (Gezora, Ganime, Kameba: Kessen! Nankai no Daikaiju, 1970), depicts another space mission, only this time it's an unmanned probe and the destination is Jupiter. On its journey, the probe is contaminated by the titular amoeba, a blue extra-terrestrial spore. When it returns to earth, crashing into the Pacific Ocean, the parasite quickly infects nearby sea-life, causing a humble cuttlefish to mutate into a tentacled kaiju which, unimaginatively, decides to run rampant. The film was Honda's first without Tsuburaya, who had passed away earlier that year and, in many ways, signals the beginning of the end of classic tokusatsu film production, which was rapidly becoming out of touch.

Space Amoeba

This was because the 1960s saw much upheaval within the Japanese film industry as cinema struggled to compete with the rapidly growing popularity of television. As such, attempts were made to try and boost waning attendance figures. First there was the New Wave, that gave rise to young, new talents such as Shohei Imamura and Nagisa Oshima to attract younger audiences. This was followed by the formation of the Art Theatre Guild in 1961, which, by 1967, provided a financial platform for more experimental cinema that (comparatively) cost a pittance to produce [ 18 ]. Increasing sex, violence and sensationalism quickly became the order of the day as the studio system began to collapse. Shintoho was long gone, shutting down permanently in 1961; the aforementioned Shochiku was on shaky financial ground; Daiei declared bankruptcy in 1971; and Nikkatsu restructured itself as the producer of softcore sex films in a bid to offer something the small screen could not provide [ 19 ].

The result: budgets were getting lower and lower as the industry monopoly, previously held by the studios, began to dissolve. Naturally, higher-cost, technically demanding genre pictures struggled to remain relevant, as well as economically competitive, often resorting to reusing footage to cut costs. For instance, in Gamera vs. Viras (1968), aliens scan the imprisoned kaiju's memories as a flimsy pretext to insert approximately 20 minutes of stock footage from previous Gamera films in the guise of an extended flashback, padding out the runtime while minimising the necessity to produce new material. The reputation of these films continued to diminish due to their increasingly ropey production values. Incidentally, five of the Showa-era Gamera films were also given the "riffing" treatment on Mystery Science Theatre 3000. By the turn of the 1970s, it seemed that space/alien invasion movies were not only out of fashion (Japanese Fantasy Film Journal founder Greg Shoemaker described Space Amoeba as 'anachronistic' [ 20 ]), but no longer financially viable – not without some outside help at least.

To be continued in Part 2

References

- [ 1 ]. Shoemaker, Greg. 'Daiei: A History of the Greater Japan Motion Picture Company', originally published in Japanese Fantasy Film Journal, issue #12, 1979, p.14

- [ 2 ]. Bikini Atoll was the location for a series of nuclear weapons tests conducted by the U.S. in the years following the Second World War. The largest device, and the cause of the contamination – code-named Castle Bravo – was detonated on 1st March 1954 and yielded a 15 Megaton payload, over twice the intended amount.

- [ 3 ]. Shoemaker; 1979, p.14

- [ 4 ]. Galbraith IV, Stuart. Japanese Science Fiction, Fantasy and Horror Films: A Critical Analysis and Filmography of 103 Features Released in the United States 1950-1992, McFarland and Co Inc., 1994. p.22

- [ 5 ]. Okamoto (1911-1996) also designed the Pairan alien costumes.

- [ 6 ]. Baxter, John. Stanley Kubrick: A Biography, Harper Collins, 1997, p.200

- [ 7 ]. Brothers, Peter M. Mushroom Clouds and Mushroom Men: The Fantastic Cinema of Ishiro Honda, AuthorHouse, 2009, p.18

- [ 8 ]. Brothers; 2009, p.126

- [ 9 ]. Galbraith IV; 1994, p.45

- [ 10 ]. Tsuburaya, Hideyo. 'Gorath Retrospective', originally published in Japanese Fantasy Film Journal, issue #15, 1983, p.10-17

- [ 11 ]. Galbraith IV; 1994, p.26

- [ 12 ]. Another issue with Evil Brain from Outer Space involved a discrepancy with aspect ratios. Episode 7 was filmed in full frame (1.33:1) whereas 8 and 9 were filmed in 2.35:1. The film was cropped to full frame when presented on U.S. television, severely compromising much of the film's cinematographic framing. This was a common problem for all widescreen tokusatsu productions (ostensibly most films from The Mysterians onwards) that were exported to the West.

- [ 13 ]. The title Voyage Into Space may have also been the result of pragmatic company precedent. American International Pictures had also released English-friendly versions of Eastern Bloc space movies such as the Soviet Planeta Bur (1962) and Czech film Ikarie XB-1 (1963). They were re-christened as Voyage to the Prehistoric Planet and Voyage to the End of the Universe respectively.

- [ 14 ]. Anon, 'The Almost but Still Not Quite Complete History of MST3K – Part 14: Battles on Many Fronts' http://www.mst3kinfo.com/history/page14.html (Accessed: October 6th 2013)

- [ 15 ]. Galbraith IV; 1994, p.177

- [ 16 ]. Rodan is a giant, mutated Pterosaurs that first appeared in Toho's Rodan (1956) and has since crossed over into the Godzilla canon. Viewers will recognise Monster Zero as King Ghidorah, another recurring character in the Godzilla universe.

- [ 17 ]. Stephens, Chuck. 'Eclipse Series 37: When Horror Came to Shochiku'. Booklet Essay. DVD. Criterion Collection, 2012

- [ 18 ]. Domenig, Roland. 'The Anticipation of Freedom: Art Theatre Guild and Japanese Independent Cinema', midnighteye.com, 2004. http://www.midnighteye.com/features/the-anticipation-of-freedom-art-theatre-guild-and-japanese-independent-cinema (Accessed: October 6th 2013)

- [ 19 ]. However, this strategy proved to only forestall the inevitable as Nikkatsu also went on to file for bankruptcy in 1993.

- [ 20 ]. Galbraith IV; 1994, p.198