Hideo Gosha: The Manly Way

- published

- 23 September 2013

Part one: 1929 – 1975

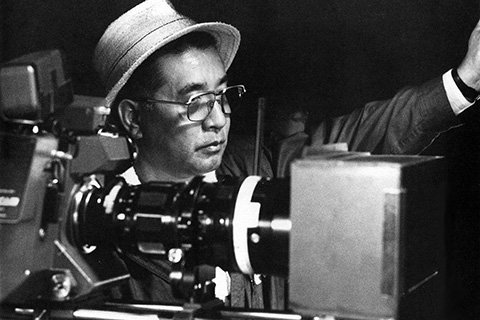

Hideo Gosha on the set of Hitokiri

Hideo Gosha has long been overlooked by Western film critics and scholars (a notable exception being Alain Silver, who dedicated several pages of his seminal book The Samurai Film to the director), and this is due to a handful of reasons: first of all, his films were hardly promoted in the West, except for Goyokin (a.k.a. Steel Edge of Revenge) which was screened in festivals such as San Sebastian, Cannes, in Toho’s American theatre, and remade by Tom and Frank Laughlin in 1975 as The Master Gunfighter. Secondly, Gosha’s chanbara work has often been overshadowed by that of his "master" Akira Kurosawa, and his "female oriented" work from the 1980s and 90s still remains little known and valued. Thirdly, Hideo Gosha himself seldom spoke well of his own work and vision, and was seen more often than not as merely a commercial and limited director (a 1969 Kinema Junpo article even dismissed him as a 'not very intelligent' director).

So what is there to be found, actually, behind both the pose of critics and the director himself? Is there a distinctive style, a vision of the world – or at least Japanese society – to be found in his work? Is there an artistic legacy? What follows provides a few tentative answers to difficult questions.

Hideo Gosha was born in 1929 in the Asakusa district of Tokyo, and therefore stemmed from the lower strata of Japanese society, from the “downtown” of the shitamachi (like, later, Takeshi Kitano). Gosha’s world was that of card players, yakuza, prostitutes, geisha, performers and street peddlers. Less intellectual than instinctive and empathetic, his vision of the world would often feed off strong and conflictive feelings, a sense of antagonistic pride. It could be said that his emotional world is patterned after ki do ai raku (feelings of passion, anger and sorrow) and that his "existentialism" is that of ikizama, a "way to live" that suggests more often than not a pathetic, conflictive way of life bent on surviving hardships, contempt for oneself and a self-destructive ego. In this emotional world, love often turns into hatred and becomes aizo, love-hate, often because men and women alike fail to nurture self-esteem and inflict emotional wounds on each other.

Hideo Gosha’s father was a tekiya (street peddler) and yojimbo (bodyguard), working notably within the Yoshiwara red-light district located north of Asakusa (portrayed in the director’s 1987 Tokyo Bordello / Yoshiwara Enjo), with whom Gosha nurtured an aizo relationship, but whose philosophy of life would prevail over the young boy: 'Life is but a battle that is best fought and won.' More or less the aforementioned ikizama philosophy, which Gosha adopted, meaning that he fought through life and managed to carve out a path for himself, leading to a sense of otoko no michi – or "the manly way" or "the cultivation of masculinity" – as a way of braving life and, when young, defending honor with "effective" use of violence. This does not mean that Gosha was a violent man, but his youthful manliness can be traced through his films, from the hectic, pro-active Three Outlaw Samurai (Sanbiki no Samurai, 1964) to more inward-looking and restrained characters like Kumokiri (Tatsuya Nakadai) in Bandit Vs. Samurai Squad (Kumokiri Nizaemon, 1978) or Sakane (Ken Ogata) in Tracked (Usugesho, 1985), reflecting on the inherent sadness of men. This means that "the manly way" is indeed evolutive, from the excesses of youth to the learnings of the later years. All in all, Gosha’s approach to existence was not intellectual but informed by typically Japanese feelings and emotions, and maybe a universal feeling of loneliness and sadness.

During wartime, at the age of 15 or 16, Gosha joined the Yokaren, the Naval Aviator Preparatory Course. He found himself among young men basically trained to become tokkotai or kamikaze pilots. But when the war ended, Gosha was left without having had to perform the final, lethal flight. According to his daughter Tomoe, this gave Hideo the will to survive at all cost; again, more than ever before, life was but a hard battle that had to be fought and – maybe – won, without any guilt or anything resembling the kamikaze’s "survival syndrome", all the more so because Gosha was not the type to intellectualize things too much.

After the war, Gosha found that he had lost brothers and sisters. He worked as hard as he could to maintain the family unit, but failed. This imbued him with a dark sense of cynicism, leading him to cast a defiant look on love and trust between people, which is perceptible in films like Cash Calls Hell. He would even later say that he found himself unable to love women, as he was too concerned with the pursuit of his own manliness.

After economics studies at Meiji University, Gosha was hired by the radio station Nippon Hoso. According to his daughter Tomoe, radio was back then the top elite media. Gosha worked as a news reporter, program producer, and learned the great value of sound, which he would apply to all his films, but when Fuji Television pursued a heavy recruitment campaign in 1957, Gosha gave in to the siren call of television and got hired. He would eventually become one of Fuji TV’s "star directors", together with Taro Okada (who married Nikkatsu actress Sayuri Yoshinaga) and Tokihisa Morikawa.

Gosha honed his directorial skills on crime and social dramas (some already featuring young actor Tetsuro Tamba), got an award from the Ministry of Culture and then tackled chanbara for the first time with his little known 1962 adaptation of Miyamoto Musashi, with Tetsuro Tamba (who played Tange Sazen the following year for Shochiku). The same year, Gosha saw Kurosawa’s Sanjuro and allegedly said: "Kurosawa has just won the battle", meaning the battle between directors for the truthful depiction of violence within the chanbara genre after the war.

Three Outlaw Samurai

In 1963, however, Gosha dauntily came up with his notorious Three Outlaw Samurai series. It seems that he originally wanted to do yet another crime drama with a very realistic depiction of violence, but a Fuji TV colleague and publicist advised him to depict such violence in the chanbara genre instead. The five characters of the intended hard-boiled crime drama, later seen on the big screen in Cash Calls Hell (Gohiki no Shinshi, 1966), were then reshaped into three samurai. Kikyo, played by Mikijiro Hira, was patterned after Kyoshiro Nemuri (whom Hira also later played for Gosha), while Sakura (played by Isamu Nagato) was probably based on Toshiro Mifune’s peasant samurai in Seven Samurai. The Three Outlaw Samurai series had the effect of a bomb being dropped on TV chanbara, with great anti-heroes and memorable action scenes. Gosha also introduced what would become to a great extent his own distinctive mark as a director: an animalistic vision of life and human beings, labelled by himself dobutsuteki na ronri (animal logic), whereby men and women, though seldom able to transcend their beastly impulses because of social violence around them, can indeed feed off this very beastliness to revive their appetite for life, numbed by sterile ideologies. To illustrate this thought, Gosha called his trio Sanbiki no Samurai, "three samurai dogs" or "beasts".

In 1964, Shochiku offered Gosha the opportunity to adapt his television series for the big screen. At that time, the five major film companies (actually six, after Nikkatsu signed the same agreement) had agreed not to work with television. As a result, Gosha’s promotion was indeed seen as an act of defiance by the Kyoto Shochiku craftsmen. Both Tomoe Gosha and Tatsuya Nakadai have said in interviews how Hideo Gosha had to face barely veiled acts of retaliation or bullying such as hiding the director’s shoes in water or letting spotlights fall down in order to frighten him. But Hideo Gosha went on undaunted and made Three Outlaw Samurai a minor masterpiece both in terms of style and content. While the style acknowledges both Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai legacy and a Spaghetti Western approach to chanbara (even more blatant in the two-part Samurai Wolf / Kiba Okaminosuke saga), content-wise the film allows a dark vision of cowardly submission to prevail, whereby the peasants give in to the yoke of social hierarchies. The fact that our three outlaw anti-heroes are hence unable to help the peasants speaks to the fact that Gosha’s ronin are not paternalistic benefactors but action men who cannot quite cope with the chaos and rampage of a world drained of feelings by greedy exploitation and materialistic ruthlessness.

The Secret of the Urn

After the success of his film version of Three Outlaw Samurai, Hideo Gosha became a sought-after director, making films again for Shochiku (Sword of the Beast, Cash Calls Hell), Toei (The Secret of the Urn, Samurai Wolf I and II) and later on also for Toho (Goyokin) and Daiei (Hitokiri). Chanbara lovers tout The Secret of the Urn and the two Samurai Wolf films, even if the former was actually a frustrating experience for the director, who was not given much creative leeway, as the project was designed for waning star Kinnosuke Nakamura and production was tightly monitored by his brother and producer Mikio Ogawa. Moreover, Gosha was not allowed to choose his collaborators and had to work with a veteran cameraman. Out of this frustration grew a desire to make a sword movie with no holds barred and a very low budget. This became the Samurai Wolf diptych. Apart from the obvious Spaghetti Western influence, the films offer a clever reworking of Kurosawa’s Yojimbo and Sanjuro whereby Kiba (played by fledgling actor Isao Natsuyagi) is not a putative father to a band of young, flighty samurai, imparting to them his paternalistic wisdom, but a lost kid fighting against a cruel, vengeful, violent man who looks like his father and is bent on killing everyone around him. While Sanjuro and Kiba have the common desire to live peacefully, Kiba retains nimaime traits (an appetite for love, hedonism) which Sanjuro’s tateyaku type no longer has. Hence, Kiba evidences Gosha’s still youthful nature, while Sanjuro highlights Kurosawa’s aging wisdom.

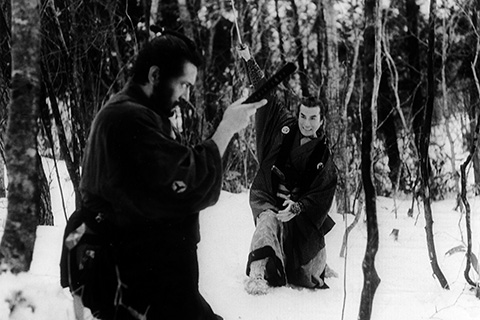

Samurai Wolf II

Despite creative freedom on this project, Hideo Gosha still felt frustrated. Both The Secret of the Urn and the Samurai Wolf films were neither commercial nor critical successes. Gosha knew he still had to grow as a director, which is what he tried to achieve with both Goyokin and Hitokiri (a.k.a. Tenchu). Goyokin was a production that would allow Fuji Television to shatter the major studio agreement and develop the channel’s own movie production section. The film was designed for Toho but could not be openly co-produced by the company since Toho was a shareholder of Fuji Television. Co-production was therefore carried out by Fuji Television and Toho’s subsidiary Tokyo Eiga.

In Goyokin, Tatsuya Nakadai (already seen in Cash Calls Hell) plays a darker version of Sanjuro, an aging samurai who is haunted by visions of death and slaughter, very much like a Vietnam vet (or a neurotic cowboy). It remains open to speculation whether the film is a reflection on wartime atrocities, since Gosha apparently never explicitly made such allusions. Much as westerns of the 1970s are about the death of the West, Goyokin is clearly about the death of a noble warrior ethic, as samurai or bushi succumb to times of greed and materialistic gain, leading to self-destruction. Very few chanbara had delved into the samurai psyche the way Goyokin does, with flashbacks replete with haunting, ghostly sounds. Though it is apparent that Gosha never fears to explore the soul (and impulses) of his characters (even more so in Hitokiri), his distinctive blend of post-Seppuku, post-Seven Samurai tragedy and generic conventions (action-packed chanbara, Spaghetti Western conventions, horror film atmosphere) is probably what restricts the scope of the film in terms of its drama. Though Hideo Gosha did admire Masaki Kobayashi’s chanbara, he also liked Sergio Corbucci’s westerns very much (1973’s Mute Samurai would even be designed after Corbucci’s Great Silence) and the motley influences do not really hold the film together nor make it transcendant. Though this judgment may seem harsh, Hideo Gosha himself did confess after making Goyokin that he felt he had reached his limits as a director and that he needed to renew his inspiration, leading up to Hitokiri, where he embraced not only the strong soul of the samurai spirit but also the weaker flesh.

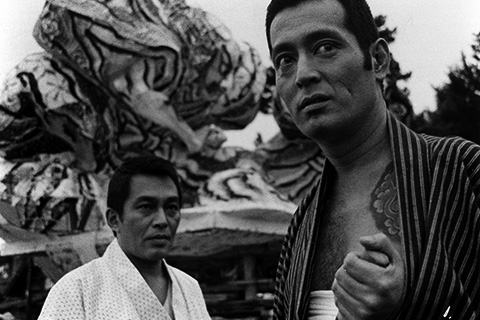

Goyokin

With Hitokiri, Hideo Gosha found everything he needed to move to a higher level: a great script penned by Shinobu Hashimoto (Rashomon), with another peasant-samurai character in Izo Okada, a great movie studio known for Kurosawa’s Rashomon and Mizoguchi’s Ugetsu Monogatari, a great actor, Shintaro Katsu, known for playing Zatoichi, and a superior film crew (set decorator Yoshinobu Nishioka, director of photography Fujio Morita). Hence, being a director with no proper movie background or film grammar, Hideo Gosha found himself entering the inner sanctum of jidai geki. This he did with butterflies in the stomach, knowing that the crew would wait for him to slip up and that he would have to rise up and prove his mettle. This he did in astounding fashion, creating breathtaking chanbara set pieces, together with choreographer Kentaro Yuasa, actors Shintaro Katsu and Yukio Mishima, and great baroque scenes like the "marathon" race of Izo Okada. Based on a true event (Okada allegedly ran more than 30 miles before swooping into sword action), this scene, when first filmed, was deemed "flat" by the crew, especially the wide shot of Katsu running alongside the river. The solution was to add a manga touch by having Katsu leaving in his wake clouds of dust, thanks to small pouches of powder fastened to his ankles.

Hitokiri

Gosha proved his mettle in several other ways during the production of Hitokiri. First of all, he did not agree with scriptwriter Hashimoto on the thematic core of the film. Whereas Hashimoto viewed Okada as a man on a path towards self-liberation (a man-dog freeing himself from a cruel master), Gosha wished to emphasize the pathetic masculine dimension of this ruthless killer, a man with empty dreams of social ascension and glory, and a ceaseless sexual impetus. Okada is indeed the depiction of a man basking in a sense of manly power and self-glorification meant to hide his weaker sides, such as his social, plebeian origins. Furthermore, to Hashimoto’s credit, Okada is indeed Gosha’s first truly "revolutionary" character, who, though not intellectualizing things, manages to say for himself and the world: ‘I now sever my ties and free myself from my master.’ Gone is the homosocial bonding of the previous films, whereby the samurai status was less important than forming empathic bonds with other outcasts; Gosha’s male (and female) characters are now left alone in a world full of darkness and uncertainty.

During postproduction, Gosha found that he was dissatisfied with the work of Daiei’s veteran editor assigned to the project. He wanted someone with a better sense of rhythm and got just what he wanted with the young Toshio Taniguchi (future editor of the Baby Cart series), who solved several problems of rhythm in conversation scenes and in Okada’s running scene, and probably decided, together with Gosha and the Daiei producers, to cut several scenes towards the end of the film, in order to tighten it up for release.

At that time, Daiei was already declining commercially. The whole film crew hoped to revive the fortunes of the company with Hitokiri, but the film only served to delay Daiei’s collapse two years later. What Gosha gained from the experience of shooting Hitokiri was not so much a better critical recognition (the film was panned by famous movie magazine Kinema Jumpo), but the sense that he could match his hectic, frenzied style with beautiful photography, production values and a more orthodox film grammar (Fujio Morita had a solid studio background and did not have the Panavision telephoto lenses Kozo Okazaki used on Goyokin). Hitokiri also allowed him to further experiment with film language, especially longer takes, as in the opening murder scene, which served to highlight how difficult killing a man can turn out to be, as in Alfred Hitchcock’s Torn Curtain. Gosha would replicate this breathtaking scene with even greater intensity (and emotion) in The Wolves (Shussho Iwai, 1971), when the two umbrella-carrying female killers are seen summoning up their physical strength in order to do away with Kunie Tanaka. All in all, Hitokiri made Gosha a better director, thanks to brilliant Daiei craftsmen who would work with him throughout the 1970s and 80s on big budget productions.

The Wolves

A year after Hitokiri, Yukio Mishima committed seppuku and was from then on a true hero for Japanese far-rightists. Though Gosha loved his collaboration with Mishima and would forever remember the writer’s words about how every man and artist, including directors, finds awareness through practice (chikogoitsu in Japanese), Gosha probably had ambivalent feelings about Mishima, thinking the writer turned actor and director might have used his film (and other films) to rehearse his own publicized death. Mishima’s death also meant that Hitokiri would no longer be shown, to comply with the wishes of Mishima’s widow, and this was clearly a disservice to the film’s reputation – until Shochiku gave it a limited theatrical re-release in 1986.

Around 1970/1971, Gosha’s television career began to take a downward turn. Actually, he never was able to replicate the success of his seminal Three Outlaw Samurai series. Audience tastes were evolving and Gosha seemed behind the times. In 1971 he tried to put an end to a streak of short-lived dramas with a waning audience, including his 1967 Kyoshiro Nemuri, by going back to his roots and producing a sequel to his groundbreaking chanbara drama, simply called The Three New Outlaw Samurai. This new series featured Go Kato, Gen Takamori and Gosha’s ex-yakuza friend Noboru Ando, also cast in The Wolves and Violent Streets, and was shot in Kyoto, on film, but it was once again short-lived. Gosha then adapted An Actor’s Revenge (Yukinojo Henge) for the small screen, with crossdressing singer-actor Akihiro Miwa (best known for the title role in Kinji Fukasaku’s Black Lizard), before his TV career came to an abrupt end due to a managerial reshuffling within Fuji Television.

He next turned to documentary (together with his assistant Ansei Yokota, who became a very talented documentary filmmaker in his own right) and made two more films for the big screen: the aforementioned The Wolves (1971) and Violent Streets (1974). The former was Toho’s attempt to capitalize on the success of Toei’s yakuza epics or ninkyo eiga, films about yakuza with a chivalrous spirit. The latter was Toei’s attempt to create a distinctive jitsuroku (realistic and urban yakuza film) with Gosha’s own brand of style, action and violence. Both films failed at the box office, although The Wolves proved to be a superior ninkyo eiga about the death of the traditional yakuza spirit, before they turned their attention to profitmaking on the eve of Japan’s imperialistic invasions. Tatsuya Nakadai plays a doomed yakuza in a disenchanted world where yakuza bosses turn into captains of industry and moneymakers. Though Gosha did intend to end the film on the traditional nagurikomi (raid against the enemy clan), Tetsuro Tamba’s refusal to play what was a naked or half-naked scene in a bathhouse called for a different ending whereby the villain survives. This bleak ending and the absence of big stars of the yakuza genre made the film a commercial failure for Toho. As for Violent Streets, it contains a more baroque streak and dance shows which announce Gosha’s will to experiment with color, theatricality and bodily expression throughout the 1980s, while retaining something of his animalistic vision of life, as yakuza exterminate each other like vermin in a kennel, while the big bosses fly over the construction sites of a new capitalist Japan.

In 1973 and 1974, Gosha worked one last time with Shintaro Katsu on the series Mute Samurai. Everybody at Daiei had expected Katsu to do a Zatoichi movie with a top-form Gosha, but this project never materialized. Unfortunately, Gosha was not allowed to direct any episode from his Mute Samurai series, the reasons for which remain open to speculation. Meanwhile, Gosha produced another series called Mushuku Zamurai, about a nukenin (fugitive ninja) played by Shigeru Amachi helping the poor and the wretched, preferably if they are beautiful women, against their oppressors, while fighting off pursuers from his own clan.

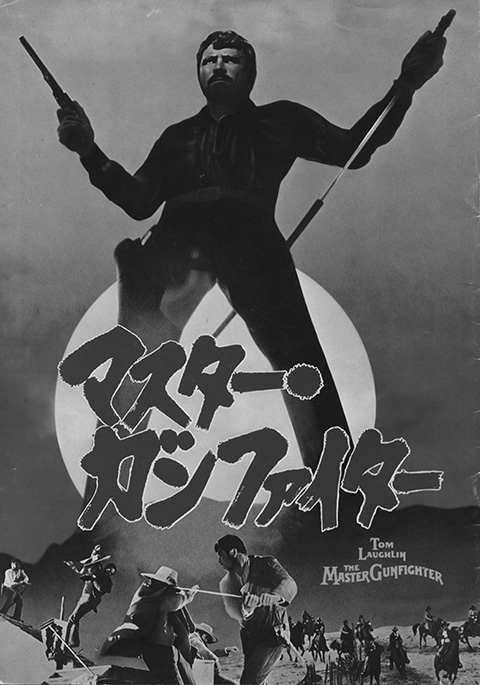

The Master Gunfighter

In 1975, Goyokin was remade in the US as The Master Gunfighter, by Tom and Frank Laughlin. Tom Laughlin was the creator of the Billy Jack character and was fascinated by Goyokin, so much so that he decided to turn it into a shot-by-shot remake as a western, in which the characters wield katana and guns alike (though they often seem to hesitate between the two!). Maybe because the film was too much of a hybrid (neither a western nor a chanbara), it bombed at the box office and Tom Laughlin’s son Frank still regrets that his father decided to do a shot-by-shot remake and not a real western with an edge. However, it should be reckoned to the film’s credit that the character of the hero’s wife (played by Barbara Carrera) is much more interesting than the one played by Yoko Tsukasa in Goyokin.

All in all, around 1974/75, Gosha’s career was at a standstill, both in television and cinema. The movie production section of Fuji TV had been angrily shut off by the chairman of the Fuji Sankei group, while Hideo Gosha no longer had star status and would have to wait until 1978/79 to make movies again, coming back on top form with Bandit Vs. Samurai Squad and, especially, Hunter in the Dark.

To be continued