Come On Feel the Noise: Sounds and Images of Uncertainty in Japanese Cinema

- published

- 3 November 2013

Hajime opens his laptop to show Yoko what he calls his 'womb of trains'; a circular collage made up of computerised images of green train carriages and black rail tracks hovering in front of a dark red spherical backdrop. Suspended in the middle of the trains and framed by this incubating redness is Hajime, in the image of a cartoon-like foetus. Almost comically, the foetus is wearing headphones and holding a contact mic as if recording the noise of the trains that surround him. The image visualises Hajime's day-to-day life. When not working in a second-hand bookshop he records the sounds of different trains, passenger conversations and public address announcements that resonate in all of the various subway stations across Tokyo. Each green carriage that collectively make up his womb of trains represent a different station and imply a multitude of different sounds. It's a chaotic and noisy image which is why Hajime, at the centre of it all, looks sad or, as he says, 'close to tears.' It's why he visualises himself in the image of a baby, as if vulnerable to the chaos that surrounds him. Yet like the foetus who is both vulnerable yet comfortable and safe in his mother's womb, Hajime finds comfort in the noise of the trains. In his sadness, amid the noise and confusion of daily life, he finds pleasure and purpose. Each recording is different, he tells Yoko, and maybe one day they 'will help with an investigation.'

This is, arguably, the seminal scene of Hsiao-hsien Hou's Café Lumière (2003). An apposite tribute to Yasujiro Ozu, the film's narrative is a languid contemplation of contemporary life in Japan. Like many of Ozu's films, nothing happens as such other than an almost voyeuristic documentation of the trials and tribulations of someone's private life and the strained relationships that encompass it. In this case, Yoko (Yo Hitoto) is researching the life of Taiwanese composer Jiang Wen-Ye. She is pregnant and her unwillingness to marry the father of her as yet unborn child disappoints her uncommunicative father and frustrates her stepmother. Yoko's friendship with Hajime (Tadanobu Asano) is palpably warmer but is equally frustrated when Hajime learns of her pregnancy. But more than the tensions and awkwardness held between its various characters, the film's strength lies with its ambling cinematography and soundscape. When watching Café Lumière we get a very real sense of what it's like to live in certain areas of Tokyo, particularly places like Jinbocho, known for its used book stores and publishing houses. When Yoko makes her way from her father's house to Hajime's book store, wandering through the various old-town Tokyo streets and sitting in the train carriages of Tokyo's subway, we can almost sense what these places feel and sound like. The film is as much about place and sound as it is its characters and the fraught tensions between them.

Café Lumière depicts a very different image of Tokyo than the image we might typically associate with it. Opposed to Sophia Coppola's same year release Lost in Translation, which shows Bob (Bill Murray) and Charlotte (Scarlett Johansson) running through the busy cross-road of Shibuya and into the clattering sounds of a Pachinko parlour, Hou's cityscape is more calm and meditative as it harks back to an almost nostalgic image of a once quieter Japan. The noisiest thing about Hou's film is Hajime's train recordings that interrupt some of the more muted scenes in the film, giving a sonic indication of the growing alienation some of us feel in the increasingly fast-paced anonymity of modern urban life.

Café Lumière

Despite their sonic differences, however, what is common between these films is a shared sense of alienation which sets the characters adrift. For Bob and Charlotte, their respective marital and relationship troubles are made all the more cumbersome as foreigners in Japan. Their inability to 'fit in' with their temporary surroundings, although at times stereotypical, is figurative of the growing isolation they feel in their lives back home. But it is this isolation which brings them together as kindred spirits separated only by age and circumstance. For Hajime a more profound isolation is at work as he struggles to make sense of the life he finds himself living, a life very much, as he explains, 'at the edge.' His alienation, indicated by the solitary figure within the womb of trains, seems more to do with a deep existential crisis concerned with the very nature of his being, which is not even appeased by his relationship with Yoko. Even in their closest moments, there is always a distance and awkwardness between them that is heightened all the more when Hajime learns she is pregnant. He is left, in his final scene, alone recording the sounds of the trains.

Noise and the image of uncertainty

According to Michel Chion's 1994 publication Audio-Vision: Sound on Screen,[ 1 ] there has developed in cinema a strong symbiotic connection between sound and image. Both mutually influence each other to such a degree that the sound of a film, and not only its soundtrack, adds value to the image. Sound is something that affects the image and causes us to view it differently from how we might have viewed it if the image were silent. In short, sound plays as big a role in contemporary cinema as the image; it's a way of making an environment three dimensional. It's what gives us access to certain environments as well as to psychological states of characters, which the image alone could not do.

In Café Lumière sound, and in particular the noise of the trains, is a way in which Hou is able to characterise Hajime's isolation as he struggles to make sense of the world and noise around him. Noise, which is often defined as a sound without meaning or something which interrupts the transmission of meaning, is a common tool used in cinema to characterise moments of confusion and alienation. In Lost in Translation, Bob and Charlotte are surrounded by noise, not only as the sound of their new and unfamiliar environment but as their inability to understand Japanese; as with any unfamiliar language, it arrives to them as a kind of noise. In both films, noise is a way of illustrating distance and loneliness where the characters struggle to maintain any semblance of meaning.

Because of the ubiquity of noise, it cannot be said to be specific to Japan or reserved for those films set in Japan. The rumbling of traffic on the tentacle-like overpasses of Osaka and the buzzing Sega signs of Tokyo's electric town, Akihabara, are no noisier than Times Square in Manhattan or the London rush hour. The problems of living or moving to the 'big city' is a theme that has structured a countless number of films and often the name of the city is of less importance than the feeling of emptiness and anonymity characters feel within it. Yet what's interesting about certain films made and set in Japan, like Café Lumière, but particularly, as we will see, with certain films associated with cyberpunk cinema, is the way in which an audible noise is explicitly connected with not only a psychological but a physical change in character. In these films, noise is still used negatively in order to show isolation and alienation. But it also takes on a transgressive and radical quality that indicates a rebellious change in character.

Because of the rebelliousness and transgressive radicality associated with the noisy gestures within these films, the concept of noise becomes suggestive of something far more dynamic and nuanced than any pejorative idea of negativity. Particularly in Shinya Tsukamoto's cult classic Tetsuo: The Iron Man (1989) the use of noise and the visual accompaniment of mutation recalls the urgency of 1960s French philosophical thought that takes identity and meaning away from stable definitions and views it more through uncertainty and difference. Certain strands of Japanese cinema have a unique relationship with noise for this particular reason as they mobilise noise not only for acoustic effect but as a way to accompany the visualisation of complex philosophical views. And while Japan's musical interest in noise is becoming an increasingly well-studied phenomenon in musicology (see for example Gaspard Kuentz and Cédric Dupire’s documentary We Don’t Care About Music Anyway), its cinematic engagement with noise and the implications of this have been largely overlooked.

Defining and visualising noise

Noise is more often than not defined negatively. And the sounds we typically associate with noise – feedback, static, machine sounds, glitches and all those things that are said to be too much to bear and which carry no obvious meaning like melody or rhythm – are generally thought to be unwanted. In music, noise is typically associated with the avant-garde and the urge to challenge convention. To use noise instead of 'typical' musical technique asks the question of music and noise all over again. This was the aim of John Cage's 4'33'': often thought to be a silent composition, it was in fact one of the most interestingly sonorous compositions of all. In this understanding of 4'33'' it becomes less to do with silence and more with a re-focusing of listening in the hope that noisy sounds might become musical ones. A more aggressive approach was that of the Futurists, exemplified by Luigi Russolo's 1913 'The Art of Noises'[ 2 ] manifesto, where noise was thought violently as a doing away with traditional musical sounds in favour of the infinite potential of noise sounds. The urgency was to break all of our old instruments and invite the noises of modern capital and industry into composition. The aim was to reinvigorate the western tradition of music with the brutality of life. In short, it was about change.

Japan has its very own unique history of noise that is equal to the cacophonies produced in the West. Neo-Dadaist group Gutai and Fluxus groups like Hi-Red Centre were interested in the anti-aesthetics of destruction and decay as modes of transgressive expression. With music in particular, the psychedelic mutations of once Western-clad rock bands who, according to Julian Cope,[ 3 ] were initially interested in following the way of the Beatles, became some of the most daring and innovative engagements with noise that have ever been recorded. And emerging out of 1980s Japan, there persists noise music: a vast genre of blistering noise that refuses any kind of musical familiarity in favour of its very own pocket of excess. What has differentiated certain Japanese noise artists, such as Toshiji Mikawa, Hiroshi Hasegawa and Masami Akita from many of their Western counterparts, rendering their sound a genre all of its own (often given the name Japanoise) is the excess of their sound. Since the early 80s they have continued delivering noise without any melodic accompaniment and without sculpting it into rhythm. Noise is left to itself, as walls of white noise, static feedback and heavy drones push the limits of the listening experience.

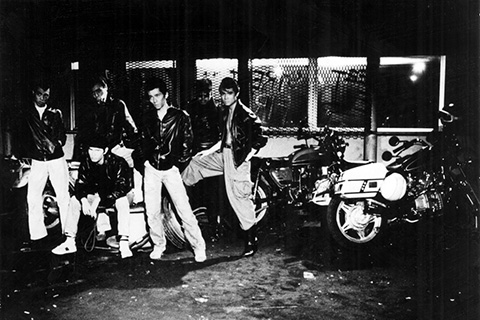

Crazy Thunder Road

But what is equal to this sonic history of noise, yet what is overlooked, is Japan's cinematic engagement with noise. It's no surprise that a country with such a rich sonic history, still currently engaged in some of the more dramatic experimentations of noise, would produce some of the world's noisiest films. Mark Player suggests in his essay Post-Human Nightmares – The World of Japanese Cyberpunk Cinema,[ 4 ] that some of Japan's noisiest and most rebellious cinematic moments, which is to say its cyberpunk moments, were borne out of music. In Sogo Ishii's films Crazy Thunder Road (1980) and Burst City (1982), for instance, the line between music and film is almost completely blurred. The Mad Max-style biker gangs that screech across the screen in the post-apocalyptic visions of rebellious youth not only, in both films, embody the vibrant and anarchic energy of Tokyo's burgeoning 80s punk scene, but the majority of the films' cast, especially in Burst City, consisted of recognisable faces from the punk scene.

In these early but seminal cyberpunk films, there are a multitude of noises at work. Screams of the brawling bike gangs; deep roaring engines; screeching breaks; and the almost broken sounds of the dystopian setting rumble and explode alongside the feedback and jarring noises of punk. The relentless bombardment of sound is matched only by the expressive camera work. Player suggests that the 'highly dynamic, handheld, almost stream-of-consciousness style shots interwoven with equally aggressive, machinegun editing' goes a long way in capturing 'the energy and restlessness of the music.' All of which, combined, work to express a radical sense of discontent turned malcontent. So noise is not only sound in these films, but a visual expression of chaos that is energised all the more by the sounds of feedback and rebellion. Ishii found a 'visual equivalent to punk music, a way to express the same philosophy and spirit with a camera instead of a guitar.'[ 5 ]

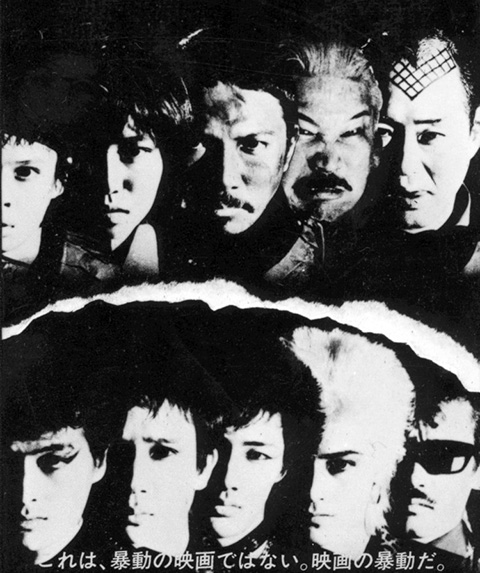

Burst City

Noise in Ishii's world takes on a paradoxical character, as it makes audible and visual a sense of discontent while simultaneously framing a sense of rebellion and a new way of belonging. It was, quite innovatively, the first time the atmosphere of Japan's discontented and anxiety-ridden youth was cinematically visualised. Noise was not only the sound of guitar feedback but the image of a lost youth who finds meaning in resistance to the dystopian nightmares characteristic of cyberpunk.

Ishii would follow up these noisy themes almost two decades later, with perhaps the noisiest film of his oeuvre: Electric Dragon 80,000V (2001). The film was a pet project to accompany Ishii's industrial noise group Mach 1.67, who not only composed much of the film’s raging soundtrack but who were known to play live with the film as their visual backdrop. Distinctive punk sounds still sounded prominently through the film. Fast paced drums, minimal chord progressions lacquered with distortion and treble, and bratty vocals tear relentlessly through the film's soundtrack like a teenager on speed. But Hiroyuki Onogawa 's sonic contribution brought an even noisier dimension to the film. Punk was not the only sound of some of the film's most memorable moments, but noise music itself, as white noise, feedback and distortion, would take a prominent role.

As Tom Mes writes in the linear notes of the American DVD release, Electric Dragon is cinema of 'pure sound and vision, that impacts directly on the nervous system, bypassing the brain entirely.' The fusion of noise and image is driven to the point of sensory overload, where even the narrative itself might be considered noise; confusing, chaotic, and surreal to the point of meaningless. The central character in the film, Dragon Eye Morrison (Tadanobu Asano, who also frequently plays in Mach 1.67) not only has the peculiar occupation of a lizard detective – tracking down lost lizards as one might investigate a missing person – but he also has an odd relationship with noise. He is charged with 80,000V of electricity and is literally bursting at the seams with the buzzing, humming and zapping sounds of electrical charge. He wakes up in the morning with a static jolt, and is saved only by his bed restraints, which he binds himself to every night before he sleeps. And when it all gets too much, he has the power to call his guitar to hand at which point he thrashes uncontrollably, making extremely loud cacophonies of guitar distortion and feedback.

Although seemingly worlds apart – one meditative and one out of control – Asano's character in Café Lumière shares a distinct similarity to his role as Dragon Eye Morrison; both have a conflicted relationship with noise. It's what confuses and binds them, yet it's also what liberates and saves them. For Dragon Eye Morrison, it's even what allows him to defeat his nemesis Thunderbolt Buddha who, charged with even more electricity and noise than Morrison, nevertheless finds himself reduced to dust as Morrison gives himself over to the limitless chaos inside of him, allowing him to be victorious in a battle to sonic death.

ELectric Dragon 80,000V

Once again in Ishii's world, noise is given a contradictory character. It's what at once threatens and disturbs identity but what also represents the potential for rebellion and change as the sound of new identities. His visualisation of noise through the punk aesthetic propagates the transgressive image of noise; noise is what comes from outside meaning and identity as a challenge and interrogation of these things. And in Ishii's world, noise is always victorious.

In his early cyberpunk explorations and even with his later effort, Ishii would cement his place as the formative Japanese cyberpunk director. Not only would his ideas be picked up by many directors down the line, but his innovative camera work and sonic explorations would also be taken up, most notably by Shinya Tsukamoto. But what is interesting about Tsukamoto is the way noise becomes internalised. It is not only a transgressive tool used to challenge convention but a visualisation of something more complex, an image and sound of the deep-rooted otherness that murmurs at the core of every human subject. For Tsukamoto, nothing is certain, and noise is how he frames this uncertainty.

Internal mutations / internalising noise

Over the years Tsukamoto has made no secret of his admiration for the work of Sogo Ishii. His use of 16mm film and own machine gun-like editing in, for example, Tetsuo might even be seen as a cinematic ode to his cyberpunk predecessor. But despite building on many of the stylistic innovations of Ishii to create his very own revolutionary approach to cinema, it was Tsukamoto's implementation of noise, as both a sonic and visual tool, that would distinguish him from anyone that came before.

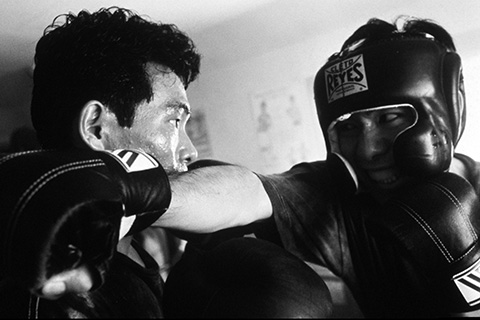

Bullet Ballet

Whereas Ishii visualises noise through the lens of a punk aesthetic of rebellion – studded leather jackets, piercings, wild haircuts, roaring bike gangs, metal chains and guitars – Tsukamoto would use the image of physical mutation and gore to indicate a moment of change. In Ishii's world, characters are living at the end, in an already rebellious state of existence across a post-apocalyptic wasteland. While the cyberpunk fantasy is enough to recall the lost world of normativity, rules and business suits, the destruction of this world has already occurred, leaving a barren industrial playground for the anarchic gangs to roam. Tsukamoto's post-apocalyptic vision is arguably more polarised as rebellious characters, seen with his depiction of delinquent street gangs in Bullet Ballet (1998), live alongside but in stark contrast to a central protagonist who is, more often than not, living the life of the salaryman, the characteristically overworked corporate businessman who came to epitomise Japan's bulging economy before the recession hit in the 1990s.

Change, in a sense, comes later for Tsukamoto than Ishii, as the salaryman characters are often forced to confront the emptiness they find themselves living in at the films’ turning point. Such is the case with Tetsuo, Tokyo Fist (1995) and Bullet Ballet. So, in post-nuclear Japan Tsukamoto retains an apocalyptic imagination but one which is, as Alan Wolfe states, no longer about whether 'survival is possible' but 'how to survive in what has always been recognised as a precarious existence.'[ 6 ] In other words, the image of rebellion and change never quite coalesce into something like punk, but are instead replaced by something inherently precarious and uncertain. So the sound and image of noise, as depicted by Tsukamoto, comes to represent something far more difficult than the usual modes of rebellion and alienation.

In his film Tokyo Fist Tsuda (played by Shinya Tsukamoto) is a disillusioned everyday salaryman who makes his way to work robotically alongside the incessant drones of marching feet and traffic. His army-like march to work is interrupted when we see him, several times, stop and stare vacantly up at the towering Tokyo buildings while the city's soundscape rumbles indifferently in the background. The use of noise in these scenes are again quite typical as they help frame a potent feeling of alienation and disconnection much like Hajime's womb of trains. We learn very quickly that Tsuda has lost touch with everything around him, even with his beautiful wife.

But when Takuji (Koji Tsukamoto), an old childhood friend and semi-professional boxer, comes back into Tsuda's life and steals away his lover, Tsuda takes up boxing. His physical transformation is hugely sonorous. As he makes his transition from boring and spineless worker to ruthless boxer, the street sounds of traffic and the marching feet of the office workers are explosively interrupted by the chaotic rumbles of speed bags being pummelled and flesh being punched. The camera work mimics the sonic transition; linear camera moves are quickly replace by hand-held jumping shots of chaotic gym activity. The fourth wall is even punishingly shattered as boxers punch the screen.

All of this is a way for Tsukamoto to reclaim a sense of physicality that he believes is being gradually lost as we slowly sink into the monotony of the daily grind. Like Yukio Mishima's 'Sun and Steel'[ 7 ] it's about remembering our body and reawakening the physicality within us all. For Mes, it's about allowing one’s inner emotions (honne) to shatter the façade of our outer, socially polite self (tatemae).[ 8 ] The alienating noise of the work place is replaced by a more frantic kind of noise wherein Tsuda is able to find a new lease of life. In the noise of the gym and among the pummelling of punch bags and flesh, Tsuda finds life again.

Yet Tsuda's transition is never quite complete but seems to be held in some kind of sadomasochistic cocoon stage. As Mes writes, destruction in Tokyo Fist is not about any kind of visible rebirth but an incubating stage where rebirth comes after, although we never quite see it as it lingers instead as a peculiar kind of implication. In Tokyo Fist, the film does not end with Tsuda and his beautiful wife sitting back on the couch watching TV just as it began. Instead, we see Tsuda's mutated face, bursting with blood as he stretches an open wound, inflicted from his brutal boxing match, into a joyous smile. The smile displays an optimism and promise of rebirth but the blood and mutation are stark indicators of the pain and destruction that has no imminent end.

Tokyo Fist

To help frame the ceaseless chaos of his disturbing and nightmarish world, Tsukamoto used industrial noise musician Chu Ishikawa for his soundtrack. Following the path laid by Ishii, Tsukamoto would accompany the erratic camera work of the gym scenes with a punishing audio accompaniment, where Ishikawa would fill the sonic space with pummelling sounds, flesh being beaten and metal hitting metal, the latter implying the merciless restlessness of a machine-like work ethic.

But it was with Tsukamoto's first collaboration with Ishikawa in Tetsuo that the full extent of the relationship between noise and mutation was not only firstly established, but most innovatively visualised. Again he would accompany fast moving images with jarring audio equivalents. Steven Brown calls this the 'velocity image,'[ 9 ] where stop-motion camera work and noise music act in sync to create a sense of disorientation and confusion as a dramatic departure from the boredom of the salaryman life. These images help create a sense of chaos and dramatic change, it's a way of rupturing not only a standard way of filming but also the characters' role within the film.

According to Brown this is exactly what Tetsuo is about. The mutation of the salaryman into the grotesque metal kaiju at the hands of the sadistic metal fetishist is about challenging the conventions of what he sees as an economically driven heteronormative society.[ 10 ] The homosexual undertones and the highly erotic and phallic nature of their encounter and eventual amalgamation, as well as the salaryman's own mutation out of his suit and into the metal beast, transgresses the dominant modes of living. The use of noise and eroticism – which interestingly in the aesthetic of Japanese noise music has been a stylistic tool used frequently for album artwork and performance – helps imagine a space of a new kind of heterogeneous identity. In this sense it follows Ishii's urgency to transgress but it differs in that the end result is not as culturally symbolic as punk, but is a strange kind of mutation that again seems to withhold the certainty of any kind of positive rebirth. The Tetsuo mutation is more about change in and of itself, regardless of result.

It's at this point that Tsukamoto becomes more nuanced than the sharp metal edges of the film might imply and where we can start seeing the connection to certain strands of French philosophical thought and his use of noise. Steven Brown establishes this connection well, when he views the Tetsuo monster alongside Deleuze and Guattari's machine-assemblage and sees the shots of tentacular cables and wires as mimicking the Deleuzian rhizome. The concept of the rhizome is a way of thinking of change disparately where connections are made between differing things in order to create new and transgressive identities. For Brown, Tetsuo is about a radical change which culminates in the final sequence where the fetishist and salaryman, existing now as one monstrous entity, threaten to turn the whole world into metal. In this sense, the use of noise is about rebellion as it is visualised through a radical mutation of the human subject and its existence.

But the use of noise and mutation in Tetsuo is not just about an active and rebellious response to a consumerist and heteronormative world. If we focus on the mirror sequence of the film, where the salaryman first glimpses his mutation by finding a protruding piece of metal on his cheek as he shaves, we get a sense that something is changing deep within his very core. Although we have to wrestle with a non-linear narrative to glean the idea that the fetishist is the demonic puppeteer behind the salaryman's mutation, the mirror scene stands alone as indicative of a different kind of change. Noise in this scene is not about a radical and violent subversion caused by the wilful rebellion of the character. In this scene, the salaryman passively undergoes noise and is exposed to what Brown beautifully calls the 'inhuman otherness that is growing underneath the surface.'[ 11 ]

Tetsuo: The Iron Man

Noise in this way in not simply antagonistic and unlike the dominant understanding of noise that defines it firstly as something negative, in Tsukamoto's world it can be heard as something more complex. He uses noise to not only illustrate a moment of rupture and change, but more interestingly as a way of framing the inherent uncertainty of being that was characteristic of a shift in philosophical thought, which came to prominence in 1960s France, that emphasised the importance of difference over stability. Tsukamoto only hints at the possibility of going beyond the chaotic and uncertain moments of noise and mutation because he seems more interested in uncertainty than any kind of resolution.

The rich history of noise that constitutes a large part of Japan's more challenging cinematic gestures reaches a crucial point in Tetsuo. Noise is no longer only a sonic indication of alienation nor is it simply something that is rebelliously put into play. Instead, Tsukamoto uses noise and the image of mutation to rethink the idea of transgression away from subversion and closer contamination, where the self is already said to be unknown to itself. And unlike many of the gestures that came before, Tsukamoto's characters never quite find themselves. The optimism of rebirth is perverted by the visual mutations that stand before us; it's not quite clear whether his lasting characters are happy or not. And this is why noise is so important for Tsukamoto because, as a sound that continually struggles to find its place through any kind of stable sense of positivity or negativity, uncertainty is the only solace.

- [ 1 ]. Michel Chion, Audio-Vision: Sound on Screen (1990), trans. Claudia Gorbman (Columbia University Press, 1994).

- [ 2 ]. Luigi Russolo, 'The Art of Noises: Futurist Manifesto' (1913), in Cox and Warner (eds) Audio Culture: Readings in Modern Music (New York: Continuum, 2004), 10-15.

- [ 3 ]. Julian Cope, Japrocksampler: How the Post-War Japanese Blew their Minds on Rock 'N' Roll (London: Bloomsbury, 2007)

- [ 4 ]. Mark Player, 'Post-Human Nightmares – The World of Japanese Cyberpunk Cinema', Midnight Eye: Visions of Japanese Cinema, 13 May 2011, http://www.midnighteye.com/features/post-human-nightmares-the-world-of-japanese-cyberpunk-cinema/.

- [ 5 ]. Tom Mes, Iron Man: The Cinema of Shinya Tsukamoto (Fab Press, 2005), 40.

- [ 6 ]. Freda Freiberg, 'Akira and the Postnuclear Sublime' (1996), in Mick Broderick (ed) Hiroshima, Nagasaki and the Nuclear Image in Japanese Cinema (London: Rouledge, 1996), 101.

- [ 7 ]. Yukio Mishima, Sun and Steel (1968), trans. John Bester (Kodansha International, 1970).

- [ 8 ]. Mes, Iron Man, 124.

- [ 9 ]. Steven Brown, Tokyo Cyberpunk: Posthumanism in Japanese Visual Culture (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), 104.

- [ 10 ]. Ibid., 107.

- [ 11 ]. Ibid., 77.