Japanese Anime and the Animated Cartoon

- published

- 29 November 2004

"The animated cartoon has made little progress except in America, but the popularity of Disney films, rivaled in universal appeal only by the films of Chaplin, gives reason to hope that there will be a world-wide development in the field of animation, each country adapting the techniques of animation to its own artistic tradition."

- Taihei Imamura, "Japanese Art and the Animated Cartoon," The Quarterly of Film Radio and Television, Spring 1953

The lights dim and the screen starts to flicker as an image of the earth, decorated with California palm trees and the Hollywood Sign, floats before us. We shift anxiously in our seats, waiting for the feature to begin, while the multi-lingual motto accompanying the Landmark Theatres chain logo announces that "the language of cinema is universal." An opportunity to watch animation auteur Satoshi Kon's latest feature on the big screen in a Detroit suburb earlier this year tempted me to agree. Following a Japanese animation invasion led by Akira (1988), Ghost in the Shell (1995), Pokémon (1999~) and Spirited Away (2001), and with films like Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence (2004), Howl's Moving Castle (2004), and Steamboy (2004) creeping over the horizon, the anime-to-Hollywood ratio in U.S. cinemas keeps tipping toward what you might find on a multiplex screen in Tokyo. I'd be chiming in with the chorus to note that anime has hit the big time in America.

The U.S. media has spared no expense in celebrating Japan's recent audiovisual achievements. Douglas McGray's 2002 Foreign Policy article on "Japan's Gross National Cool" in particular sparked the attention of eager journalists and otaku across the country, inspiring many to pick up McGray's interpretation of "soft power" and help propel the bandwagon of praise for the contemporary cultural successes of America's partner in democracy. Cellular phones, cat character goods, and horror movies sometimes take the spotlight, but anime commands a privileged role in this production. With the enthusiastic support of viewers of all races and genders, Japanese cartoons are becoming a colorful illustration of Japan's status as a "perfect globalization nation" (McGray) in a melting-pot transnational market that has already transcended the U.S.'s reach.

Or that's what they say. I hate to sound unenthusiastic, but globalization or no, the anime boom has been in the works for decades. Regardless of the rapidly growing numbers of Japanese animated videos at Blockbuster and Wal-Mart over the last 15 years, this "breakthrough" is something of an exaggeration, and the implication that it's proof of a magical cultural force working independent of U.S. influence and economics raises big questions to say the least. Not only has Japanese animation been part of the world all along, but the world has always been part of Japanese animation.

The first anime export was in 1917, when Seitaro Kitayama's Momotaro was shipped to France three months before its release in Asakusa, Tokyo and less than a year after the production of Japan's first animated film, Oten (a.k.a. Hekoten) Shimokawa's Imokawa Keizou Genkan Ban no Maki, (or his Dekobou Shingachou: Meian no Shippai, depending on who you ask). Production of short films, including a handful of foreign releases, continued for years until theatrical features became possible in the early 1940s thanks to sponsorship by government forces on a very ambitious transnational project: war. While Japanese and American soldiers battled each other on land and sea, cultural hero Momotaro and his Disney-like animal buddies trampled Bluto, Popeye, and the devilish foreign Navy before the eyes of anxious young viewers. Unfortunately for Momotaro his animated dreams didn't come true, and when the postwar commercial cell-animated film industry - granddaddy of the "anime" we know today - developed in the shadows of Disney releases and Occupation censorship, it was instantly and explicitly international.

Hiroshi Okawa, president of Japan's major postwar cartoon studio Toei Doga, emphasized the possibilities of animation to traverse cultural and linguistic barriers in a way that live action film couldn't. He sent Japan's first color cartoon feature Legend of the White Serpent (Hakujaden, 1958 / US version: The Panda and the White Serpent, 1961) to the Venice Children's Film Festival, where it won the Grand Prix and was picked up for local distribution by a handful of countries including the U.S. Okawa's studio made its first proper international distribution contract with Shonen Sarutobi Sasuke (1959 / US version: Magic Boy, 1961), which also won at Venice and was recruited by M.G.M. in 1960. By the time Toei had proven the speed and effectiveness of its low-cost cartoon production with its third film, Journey to the West (Saiyuki 1960 / Alakazam the Great, 1961), the company was receiving offers for overseas co-productions. The title of a 1961 Asahi Newspaper article about Toei's international releases eagerly summed up the mood: "Japanese-made cartoon movies making dollars! Cheap, easy to understand . . . but how long will it last?"

Well, it never stopped. Most of Toei's early features were sold internationally, and when Osamu Tezuka developed his rival Mushi Productions and created the first animated Japanese TV series Tetsuwan Atomu (Astro Boy, 1963~), that was picked up overseas as well. The golden years of Japanese animation were sparkling with international sales and co-productions, and American companies left their fingerprints everywhere, translating, editing, and packaging anime for the world.

Critics often consider the supposedly "international" (or un-national, ethnically neutral - in other words, Western-looking) look of anime character designs and settings one of the reasons Japanese cartoons have proven so saleable, but the ethnicity of animation is something of a paradox. The rhetoric of neutrality holds no water in regards to films like Anju to Zushiomaru (1961 / US version: The Littlest Warrior, 1962) or Wanpaku Oji no Orochi Taiji (1962 / US version: The Little Prince and the Eight-Headed Dragon, 1964), both of which featured stories and characters drenched in stereotypically Japanese images.

On the other hand who would have guessed that the Burl Ives-narrated Christmas classic Rudolph, the Red-Nosed Reindeer (1964) was actually Japanese animated, or that the Rankin-Bass cartoon TV version of Tolkien's The Hobbit (1978) was drawn by the same Japanese studio that made Miyazaki's Nausicaa: Valley of the Wind (Kaze no Tani no Naushika, 1984 / Warriors of the Wind, 1986) six years later? Did American kids acknowledge the Japanese allies who helped fight the foreign terrorists in Marvel's G.I. Joe and groom the stubby pink stallions in My Little Pony in the mid-1980s? History has remembered many interesting anecdotes out of the decades of transpacific anime exchanges, such as the insistence of the Civil Rights-conscious National Broadcasting Company (NBC) in 1965 to have all of the bad guys colored white, and definitely not black, in Osamu Tezuka's Jungle Emperor (Janguru Taitei 1965 / US version: Kimba the White Lion, 1966). Tezuka Pro actually drew the series in color specifically with foreign distribution in mind, as a domestic release alone would not have covered the high production costs. Thanks to foreign dollars, Leo became Japan's first color animation TV series.

With such a tangled and uncertain past, why are we so pleased now that we're watching anime instead of cartoons? Anime series are still regularly edited for overseas TVs and movie screens, although a greater interest in "authentic" Japanese animation and the greater capabilities of DVD and computer technology have resulted in uncut, restored, or subtitled video versions for many titles. With the vague odor of culture as a selling point, the tables have turned; a Japanese origin is now emphasized while Western intervention is hidden in the shadows.

Nonetheless, U.S. companies are as active as ever. The first big wave of "cult" Japanimation titles that started around 1990 only arrived at the local video store with the assistance of U.S.-based distribution companies like AnimEigo, A.D. Vision, and Central Park Media. Fans and industry commentators often praise Japanimation's remarkable success in August 1996 when the VHS release of Mamoru Oshii's Ghost in the Shell took number one on the Billboard video sales chart, but do they remember the role of Western co-producer and distributor Manga Entertainment? Manga Entertainment surely does, their website justly boasting of "cultivat[ing] the international theatrical market for Japanese animated feature films." The incredible international success of Spirited Away (2001) came only five years after Tokuma Publishing signed an international distribution contract with Disney's Buena Vista Entertainment. Japanese animation did not appear out of nowhere on the international market; it's been here all along. The mysteriously international Japaneseness claimed by Western critics today was cultivated and marketed only after America's rapid "discovery" of Japanese animation around the early 1990s, which itself followed decades of foreign releases and ambiguously transnational co-productions.

I'm not sure if New York Times film critic Elvis Mitchell tried to make a similar point or missed the joke when, in his vote for the French-Belgian-Canadian-British co-production Triplets of Belleville on his 2003 Movies of the Year list, he praised animation as being "the last true expression of national individuality" in film. Perhaps it's lucky for anime fans that a new generation of scholars has stepped up to the plate to problematize Japanese animation's origins with a stiff shot of the one thing that cultural claims lack - history. Koichi Iwabuchi's essay "How 'Japanese' is Pokemon?" in the recent Pikachu's Global Adventure: The Rise and Fall of Pokemon, and Satoshi Kusanagi's fascinating book on the history of Japanese animation in America, Amerika de Nihon no Anime wa Do Miraretekita Ka? [trans: How has Japanese Anime Come to Be Seen in America] - both of which helped to fuel this essay - and the publications and presentations of a handful of other scholars in America, Europe, and Asia have served in different ways to fill some of the potholes left by the North American reification of anime and check the wave of fandom that has sterilized the significance of Japanese animation to a simplistic Disney vs. Anime binary. Hopefully as the anime-tion of American entertainment continues, the history of animation will grow as well.

But for a start, we may not need to look deeper than our own TV screens to see what's happening under the surface. One of the most fascinating qualities of these films is the way they wear their hybridity on their sleeves. Heavily orientalized as many of the prewar shorts and early Toei films were, Legend of the White Serpent is a remake of a Japanese version of a Chinese folk tale, a romantic look back at a fertile colonial territory that suddenly became inaccessible to Japanese citizens after the war.

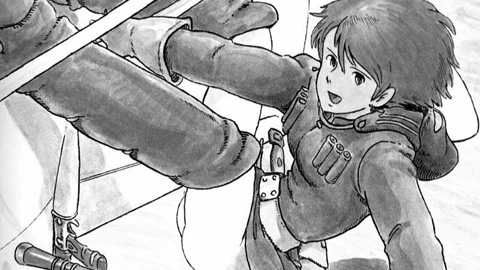

Miyazaki has always been frank about the impression Legend of the White Serpent left on him, and his Nausicaa is a much more complex meditation on national borders, war, neutrality, economic development, and the contamination of one "culture" with another. As much as Otomo's Akira is a futuristic cyberpunk sci-fi fantasy, it's also an epic look back at the trauma of Japanese economic growth and the anti-US-Japan Security Treaty movement in the 1960s (the film's climax is set in an apocalyptic Tokyo Olympic Stadium, an icon from a time when the economics of TV anime were starting to drastically limit the animation playing field.) Ghost in the Shell questions physical limits and complicates ideas of national ideology and identity as if playing a joke on the international money flow and distribution system that made it a Japanimation success. Miyazaki's Spirited Away is possibly the most striking example of them all; a virtual encyclopedia of international animation spectacle, visually referencing everything from U.S. and European fantasy film to Disney cartoons and iconic images from anime's (especially Toei's) own history. In her quest to return to a new and uncertain home, Chihiro laboriously acts out anime's wandering steps as she struggles to gain a foothold while being cast into various identities by forces foreign and domestic.

Regardless of Miyazaki's emphasis on the cultural specificity of Spirited Away's story and mise-en-scène, his Academy Award-endorsed fairy tale may be the most compelling example of how these films not only materially crisscross and challenge national identities as they always have, but also embody that quest narratively and visually in a colorful pastiche of fantasy and adventure.