A History of Sex Education Films in Japan Part 3: The Seiten Films

- published

- 25 August 2009

In the 1950s the major film studios in Japan produced a number of films dealing in one way or another with sexual education. These so-called seiten eiga films can be divided into two groups: a smaller one produced mostly by Shochiku in 1950 and a larger group produced by several major companies between mid-1952 and early 1954. The former are the subject of part 3, the latter will be dealt with in part 4 of the series "A History of Sex Education Films in Japan".

Japanese dictionaries are rather vague when it comes to the term seiten. Sanshodo's Kojirin, Kodansha's Nihongo daijiten and Kodansha's Nihongo daijiten have no entries at all. Shogakukan's Nihon kokugo daijiten loosely defines seiten as "books in which various things are written about sexual matters" (sei no kotogara ni tsuite iroiro to kaite aru shomotsu), Shogakukan's Daijisen also generally defines it as "books written about sexuality" (sei ni tsuite kakarete iru shomotsu). Gakken's Kokugo daijiten more specifically defines seiten as "books explaining about sexuality" (sei ni kansuru koto o kaisetsu shita hon), and Iwanami's Kojien defines it as "books made for the purpose of providing sexual knowledge" (seichishiki o ataeru tame ni tsukutta hon). The Japanese Wikipedia has no particular entry, but a category "seiten" specified as "textbooks about sexuality" (sei ni tsuite no kyokasho), with links to "Kama Sutra", "Aranga Ranga" and Van de Velde's "The Perfect Marriage". Depending on the context, seiten can be translated as "sex encyclopedia", "sex handbook" or "sex manual".

The term seiten was first coined in the 1920s, when the new term sei gained ground and replaced older terms for sexuality such as iro or shiki (see part 1). Akatsu Nobumasa's book Seiten, first published by Seibundo in August 1927 as third volume of its Dai Nihon hyakka zenshu (Great Encyclopedia of Japan) series, was the first book featuring seiten in its title. Akatsu, a medical doctor, was a student of the famous Japanese bacteriologist Noguchi Hideyo, who had discovered the agent of syphilis in 1911 (his image adorns today's 1000 Yen bill). Akatsu translated several of Noguchi's books originally written in English into Japanese - e.g. his Serum diagnosis of syphilis (1911; jp. Baidoku no kessei shindan 1918) - and wrote a number of books on syphilis and other venereal diseases himself, such as Osoroshii seibyo no konchi to densen yobo (Cure and prevention of dreadful venereal diseases; 1926), Shinkei suijaku chihosho to baidoku (Neurasthenia, Dementia and Syphilis; 1927) and Seikun (Sex instructions; 1928). The latter, featuring the alternative German title Ein Ratgeber für Geschlechtskranke (Guidebook for people with venereal disease), was published as special issue of Kodansha's "Pocket Book" series and was intended as a sex education book for the masses. Sex education (seikyoiku) and social education (shakai kyoka) was also the self-declared aim of Akatsu's Seiten. In the preface Akatsu defines as the book's purpose the diffusion of "only scientifically correct knowledge" (nanigoto mo kagakuteki ni tadashii chishiki). The 530-page volume treats every possible aspect of sexuality in a sober and factual manner and lives up to its title "Sex encyclopedia". A reprint was published after the war, in 1948. The publisher Toseisha, however, split it into two parts and published them as Seiten kyoiku-hen (Sex Encyclopedia - Education) and Seiten byori-hen (Sex Encyclopedia - Pathology).

Even more successful than Akatsu's "Sex Encyclopedia" was the book of the same title written by Habuto Eiji and published by Hokodo Shoten in January 1928, less than half a year after Akatsu's book. Habuto was also a medical doctor and gynaecologist as well as a very prolific writer of popular books on sexual matters and sexology. He had briefly studied in Germany, the "motherland" of Sexualwissenschaft; in 1915 he had written, together with Sawada Junjiro, the highly popular Hentai seiyokuron (Studies of sexual perversion) along the lines of Richard von Krafft-Ebing's Psychopathia Sexualis (1886). That Habuto's book Seiten was also very popular can be seen from the number of reprints. In 1934, the Ginyokai Shuppanbu published the 10th edition. [Although best known for his sexological books, Habuto also wrote a book on cinema, Kinema suta no sugao to hyojo (The honest face and facial expression of film stars; Nankai Shoin 1928), in which he portrays 70 film stars of his time.]

Similarly popular was Shimada Hiroshi's Onna seiten - Fujin no igaku (Sex Encyclopedia for Women - Medicine for Ladies), first published in September 1928 by Seibundo. When the publisher Kinseido reissued the comprehensive volume in 1939 it was the book's 49th edition.

The books mentioned above are typical for the liberal 1920s when "sexological studies" flourished in Japan. With the rise of Japanese nationalism and militarism in the 1930s, however, these sexological studies were deemed unnecessary or even dangerous and, with a few exceptions like the above mentioned Onna seiten, which became a bestselling manual for pregnant women, they more or less vanished from the publisher's catalogues.

After the war, the occupation authorities replaced the strict censorship regulations of the wartime regime with a new and - at least with respect to sexual matters - less restrictive censorship code. This had an immediate effect on the publishing market which was flooded with more or less explicit books and magazines, including numerous publications featuring the label "seiten". From the serious educational to the sensationalist bawdy, the range of these seiten books and articles was quite amazing.

For one thing, the classical seiten - the Kama Sutra and Aranga Ranga from India, Le jardin parfumé from Arabia or the El-Ktab from Turkey - were published for the first time legally in Japan. At least three different translations of the Kama Sutra had been published before the war - most importantly a translation from the Sanskrit by the eminent indologist Izumi Hoei, Indo aiko bunkenko, published privately in 1928 by Bungei Shiryo Kenkyukai. Like the other pre-war translations, however, these were private publications and banned by the authorities.

In 1947 Takahashi Tetsu, who in the coming decades would become Japan's most widely known sexologist, compiled a volume about these forbidden books with the title Hakkin toshokan seiaijutsu-hen and the English subtitle Study on the Sale Prohibited Literature in Japan. The Civil Information and Education department (CIE) of the US occupation forces raised objections to the book and stopped its sale. In 1948 it was re-issued under a different title, Seiten kenkyu seiaijutsu-hen (Sex encyclopedia studies - Love techniques; Seikagaku Shiryo Kankokai, 1948), and this time it passed censorship. In the same year Fuyosha published Ogata Osamu's Zukai seiten (Illustrated sex encyclopedia), which followed Maki Kiyoshi's Seiten (Izumi Shobo, 1947).

The bulk of seiten literature, however, was rather more sensational and bawdy; it was published in the vast number of magazines, generally known as kasutori zasshi, which mushroomed in the late 1940s and which, often under the banner of "education" and "enlightenment", provided its readers with juicy stories and titillating entertainment. They featured a large number of seiten specials or published special seiten issues. The magazine Daiichi yomimono for instance put out a rinji zokan (extra issue) in 1949 entitled Kanzen naru seiten (The perfect sex encyclopedia). The title was of course a pun on Theodoor Hendrik van de Velde's popular bestselling book Het volkomen huwelijk (The Perfect Marriage, 1926) which was first published in Japan in 1946 by Fumoto-sha under the title Kanzen naru kekkon and which itself became a seiten classic.

In March 1949, and here we finally get to the films, the magazine Heibon started a new serialized novel with the title Otome no seiten (Sex encyclopedia of a maiden) by popular writer Koito Nobu, which was made into a film by Shochiku. Koito Nobu, born in 1905, was one of the most successful female writers of popular fiction in the post-war period. In the same year, 1949, her novel Omokage (Face) was nominated for the Naoki Award, which after a five-year break was resumed again that year. She had been closely connected with Shochiku since 1941 when a script of hers which she had submitted (under her real name Koito Shinobu) to a "national film screenplay contest" (kokumin eiga kyakuhon boshu) held by the Cabinet Information Bureau was selected and turned by Shochiku into the film Hahakogusa (Cottonweed) directed by Tasaka Tomotaka (a remake was directed by Yamamura So in 1959). [Runner-up of the contest, by the way, was Kurosawa Akira, then still assistant director at Toho.] With Ichikawa Tetsuo's Haha no hi (Light of a mother, 1947) and Takagi Koichi's Shoya futatabi (First night once more, 1949) Shochiku produced two more films based on Koito's novels before Otome no seiten. Producer of all three films as well as of the follow-up Niizuma no seiten (Sex encyclopedia of a newly-wed woman, 1950) was Ishida Seikichi.

The announcement of the magazine Heibon, which labelled itself "entertainment magazine for songs and films" (uta to eiga no goraku zasshi), makes it clear that the film adaptation of the novel Otome no seiten by Shochiku was decided from the start: "Start of the sensation novel chosen by Shochiku to be adapted to film". In fact, the novel was written on request of producer Ishida Seikichi, who wanted to make a film dealing with the issue of sex education. At first Koito resisted Ishida's persistent request, but finally she gave in and started reading the material he has collected for the novel. Ishida took Koito to a sexological study group in Asakusa and introduced her to the head of a clinic in Asakusa which specialised in the treatment of venereal diseases. The novel was advertised by Heibon as the "first Japanese novel dealing with the problem of sex" (wagakuni de hajimete kikaku sareta 'sei' no mondai shosetsu) and as a "great tragedy of a woman in tears caused by her lack of sexual knowledge" (sei no muchi yue ni naku onna no daihigeki). The sixth and final instalment of the novel was published in August 1949, the same month the magazine Shinario bungei published the script version Otome no seiten - kanzen naru seishun no tame ni (Sex encyclopedia of a maiden - For a perfect springtime of life) - the second part of the title again alluding to van de Velde's Kanzen naru kekkon.

Otome no seiten is a good example for Shochiku's new production line initiated by its first "production rebuilding plan" announced in April 1949 in order to counteract the studio's continuing slump. One step was the increase of literary adaptations (gensakumono) at the expense of original screenplays which Takamura Kiyoshi, head of the production department, considered one factor in the failure of Shochiku's films. In the case of Otome no seiten Shochiku tied up with Koito Nobu even before the novel was published. The film's success eventually led Shochiku to sign a contract with Koito to bind her exclusively to the studio. Another measure to strengthen Shochiku's production was an increased exchange between their studios in Kyoto and Ofuna. Several directors from the Ofuna studio were dispatched to Kyoto, among them Yoshimura Kozaburo (Shitto/Jealousy, Mori no Ishimatsu/Ishimatsu of the forest), Kinoshita Keisuke (Hakai/The Outcast, Yotsuya kaidan/Yotsuya ghost story, Yaburedaiko/Broken drum) and Nakamura Noboru (Eden no umi/Eden by the sea, Koibumi saiban/Love letter trial [after a novel by Koito Nobu]). The director of Otome no seiten, Oba Hideo, was also dispatched to Kyoto, and it was the first film he shot there after 1945 (he had made three films in Kyoto during the war). Oba was a reliable, but so far not particularly distinguished director who had made his debut in 1939 and had made more than two dozens films for Shochiku. His rise to fame came three years later, in 1953, with the Kimi no na wa (What is your name?) trilogy, one of Shochiku's biggest successes ever. A third step was a shift towards more popular fare, to comedy, music films, suspense films and other entertainment movies. This strategy proved successful. Whereas the box-office returns of Shochiku's more ambitious films of 1950 such as Yoshimura Kozaburo's Shunrai (Spring Thunder) and Kinoshita Keisuke's Kekkon yubiwa (Wedding ring) fell far behind expectations, their entertainment films such as Sasaki Yasushi's Omoide no borero (Bolero of Memory), Ichikawa Tetsuo's Horo no utahime (The wandering songstress) with Misora Hibari, and Mizuho Shunkai's Pekochan to Densuke (Pekochan and Densuke) became box-office hits and helped Shochiku to overcome its slump. One of Shochiku's most successful films of 1950, however, was Otome no seiten, released on March 19, 1950.

What was the film about? The policewoman Iwashita Tomoe calls on the teachers of a girl school, because one of their students, Ishihara Mieko, has been taken into protective custody. At the school Tomoe meets Tachibana Tetsuya, a young teacher whom she had met before at a radio discussion in which he had been taunted by other participants after deploring the decline of sexual morals. He is worried when he learns that Mieko has been found to be pregnant, but he opposes the decision of the school council to expel Mieko on the grounds of bad behaviour. Tetsuya lives at his former teacher's house. He had been in love with his teacher's daughter Chizuko, but after the war and his repatriation Tetsuya finds Chizuko completely changed. The once pure girl had turned into a rebellious demimondaine. The more Tetsuya tries to get away from Chizuko, the more she clings to him. Chizuko takes in Mieko, who had run away from home, and in order to annoy Tetsuya she declares that she will take care of the girl. Convinced that the lack of proper sex education was the reason for Mieko's blunder, Tetsuya and Tomoe visit Prof. Fukumoto of the Association for Sex Education to ask for his advice. With his support they try to introduce a sex education program at the school. When they learn that Chizuko has taken Mieko to a midwife to get an abortion, Tetsuya and Tomoe rush there and arrive just in time to rescue Mieko, who resolves to become a better person. Mieko helps Tetsuya, Tomoe and Prof. Fukumoto organize a lecture on sex education at the girls' school, but the lecture is disrupted by the good-for-nothing Kawai who had seduced Mieko and got her pregnant. Tetsuya, trying to protect Mieko, is stabbed by Kawai. He is taken to the hospital, but he has lost a lot of blood and needs a blood transfusion. Since the doctors consider Chizuko's blood impure they use Tomoe's blood instead. Chizuko finally gives up on Tetsuya, and Tomoe and Tetsuya get together. They decide to take care of Mieko and her child and live a simple but happy life.

Shochiku must have sensed the commercial potential of this film and rather aggressively advertised it with slogans such as "the most problematic feature film of this spring season!", "pregnant school girl in uniform!", "tragedy of a maiden knowing nothing about sex", "the dangers of sex play (momoiro yugi)" and "the marvellous film to the sex novel". To stress the "educational" character of the film it was released together with the sex education film Ai no dohyo (A Guide to Love) produced by Osaka Eigajin Shudan (see part 2).

The reactions to Otome no seiten were ambivalent. At the box-office the film was a big success. In fact, it was one of Shochiku's highest-grossing films of the year. The critics on the other hand were less enthusiastic. Some tried to acquire a taste for the educational message of the film. The doctor Oshima Masao, for instance, in a review in the Miyako Shinbun recommended the film to all teachers and educators in the country. As a doctor, however, who himself was involved in sex education he finds fault with some incorrect depictions (like with a diagram of the fertilization of an egg). He also objects to the old-fashioned vocabulary (mukashi no gakujitsugo) and stresses that additional sex education lectures would enhance the effect of the film. The majority of critics, however, were reluctant if not dismissive. In a review in Eiga Hyoron the film critic Ogi Masahiko jeered that for all the talk about "sex education" the film was a "totally unreliable sex encyclopedia" (do ni mo tayorinai seiten). For that it would need more than just the insertion of a brief and inadequate sequence from a sex education film. The film critic Futaba Juzaburo condemned the film as "detestable" (iyarashii) and "beyond good sense" (ryoshiki no han'i-gai). He even called the making of a film like that a "kind of criminal act" (isshu no hanzai koi). In a discussion in the magazine Eiga Geijutsu he branded the film a "phenomenon of hooch affliction" (kasutori-byo gensho) referring to the low-quality moonshine (kasutori) that was namesake of the multitude of bawdy and lewd magazines of the post-war era.

[On a side note, the discussion in the July 1950 edition of Eiga Geijutsu is a sham. All four participants - Futaba Juzaburo, Kazetani Itsu, Ukiya Kazuo and Horii Aruto (a pun on Hollywood) - are one and the same person, whose real name is Ogawa Kazuhiko. Among his many pennames was also Uda Nitto (= Whodunnit). The name Futaba was chosen out of deference to Futabatei Shimei, whose translations of Turgenev had deeply impressed the young Ogawa.]

To cash in on the success of Otome no seiten, Shochiku hastened to produce a follow-up, Niizuma no seiten (Sex encyclopedia of a newly-wed woman), again based on a novel by Koito Nobu serialized in the magazine Heibon from September 1949 to May 1950 and released on July 18, 1950. The staff of the film was identical except for the screenplay writer. Inomata Katsuhito was replaced by Mitsuhata Sekiro and Hashida Sugako at the beginning of her long and very successful career. The film was announced as "sister picture" (shimai-hen) of Otome no seiten and was accompanied by another short film of Osaka Eigajin Shudan. Whether this short, Naraku no hodo (Pavement to Hell), was a sex education film in the fashion of Ai no dohyo is not clear. The main film, in any case, though featuring seiten in its title, was less outspoken about sexual matters than its predecessor. For this reason Eiga nenkan (Film Yearbook) - perhaps following the classification of the Motion Picture Code of Ethics Committee (eiga rinri kitei kanri kitei), the Japanese censorship agency established in June 1949 - classified Niizuma no seiten, which revolves around two couples and their marriage problems, as a "melodrama" and not as a "sex education film" (seikyoiku eiga) like Otome no seiten.

There is another film by Shochiku, however, that Eiga nenkan lists as "sex education film": Kiken na nenrei (Dangerous Age), released on April 2, 1950. This film is not to be confused with the film of the same title produced by Nikkatsu in 1957 directed by Horiike Kiyoshi and based on Ishizaka Yojiro's bestselling novel of the same title. It tells the story of three girls on the verge of adulthood. While two of them engage in "sex play" (momoiro yugi), the third, a Christian, tries hard to convert a thug to a decent life. Capitalizing on the success of Otome no seiten the previous month, the film was advertised by Shochiku as "sister picture" of Otome no seiten and was sold with similar slogans such as "Schoolgirls playing with fire" (jogakusei no hiasobi) and "Love game of a dreadful adolescence" (osorubeki shishunki no hiasobi). Concerning their planning, however, the two films had little in common. Kiken na nenrei was produced by Kogura Takeshi and made by Shochiku's Ofuna studio and not its Kyoto studio. Originally Kinoshita Keisuke was scheduled to direct the film, but eventually the direction was assigned to Hara Kenkichi, a former assistant director of Ozu Yasujiro who had been directing films for Shochiku since 1937. The screenplay was written by Shindo Kaneto. It was one of the last screenplays Shindo wrote for Shochiku before leaving the studio in March 1950 together with director Yoshimura Kozaburo after their project Nikutai no seiso (Garment of the flesh) had been rejected by the studio bosses. The following year they realized the film with Daiei under the title Itsuwareru seiso (Clothes of deception). By leaving Shochiku of his own volition, Shindo avoided being fired by the studio during the red purge that began shortly afterwards.

Shochiku was not alone in turning towards more salacious topics in their films. In the media the term seiten eiga came to denominate not only the "sex education" films produced by Shochiku, but it was used in a more general sense for films dealing with sexuality and eroticism in a more explicit way than the Japanese audience was used to so far. In a review of the films of 1950 in the film journal Kinema Junpo, a highbrow round of nine leading film critics single out the "seiten eiga" as "the most prominent trend of the year in Japanese cinema" (kotoshi no ichiban okina keiko). In another review, Kinema Junpo in its New Year 1951 edition identifies "immoral films" (fudotokuteki eiga) as one of four major trends (the others being the resurge of jidaigeki films, anti-war films and American Western movies). The "immoral films" referred to the same group of films, which were also labelled "bed films" (nedoko eiga), "flesh films" (nikutai eiga), "lust films" (shunjo eiga), "erotic films" (kanno eiga), "pulp films" (getemono eiga) or "seiten eiga". Beside the above mentioned Shochiku films these included Nikutai no hakusho (White paper of the flesh; Shineigasha = Toei), Aru fujinka-i no kokuhaku (Confession of a gynaecologist; Daiei), Zoku furyo shojo (Delinquent girls Part 2; Toyoko Eiga), Jogakuseigun (A group of schoolgirls; Toyoko Eiga), Josei tai dansei (Women vs. Men; Oizumi Eiga = Toei), Yuki fujin ezu (Portrait of Madame Yuki; Takimura Production = Shintoho), Shiroi yaju (White Beast; Toho), Dotei (Male virgin; Shochiku) as well as Tokyo juya (Tokyo nights).

Among these the most prominent and most severely criticised film was Mizoguchi Kenji's Yuki fujin ezu. Based on Funahashi Seiichi's bestselling novel belonging to the category of "kanno shosetsu" (novels about sexuality), the film focuses on the erotic overtones of an affair of a former aristocratic woman and depicts the social and moral changes in post-war Japan. Criticized for its sexual frankness, the film is a good example for the changing attitudes of Japanese cinema towards sexual or erotic topics, but it is hardly of interest for our purpose, which is the investigation of sex education in Japanese films. The same can be said about Hara Kenkichi's Dotei and Saburi Shin's directorial debut Josei tai dansei. It is interesting, however, that in all three films the heroine is played by the same actress, Kogure Michiyo.

Of an altogether different kind was the film Tokyo juya, directed by Numanami Isao. It was the first film produced by Shueisha, a film developing laboratory founded by Yoshida Eisuke, the former head of the production department of Kokusai Eiga. In July 1950 Yoshida abandoned film development and switched to film production. Although Tokyo juya credits veterans such as Kamiyama Sojin, Mayama Kumiko and Tatematsu Akira it was basically a tableau of striptease scenes typical for the strip film genre that began emerging at that time. The film was distributed by Tokyo Eiga Haikyu, the distribution company established in autumn 1949 by Tokyu Corporation as distributor for the films made by Toyoko Eiga and Oizumi Studio. In 1951 all three companies were merged into Toei (which embodied the merger in its triangle logo). Tokyo juya was released in a triple bill together with two other films, Sei to kofuku (Sex and Happiness) and Sutorippu Tokyo (Tokyo Striptease). The former was a basukon eiga (see part 2) produced by Riken Eiga, directed by Iwahori Kikuo and first released in November 1949 (incidentally "sei to kofuku" was also the catch copy of Saburi Shin's Josei tai dansei). The latter was a striptease film directed by Otani Toshio and produced by Ginsei Production starring striptease star Hirose Motomi. Otani had started his career in 1924 as an actor under the name Mizutani Toshio. In 1932 he joined Nikkatsu and worked as a director first in their Uzumasa Studio, later in their new Tamagawa Studio. In 1936 he changed to PCL and eventually to Toho before joining the Manchurian Film Cooperative Manei. After the war he had difficulties to resume his career and ended up directing bawdy comedies and strip flicks like Tokkan hadaka tengoku (Rush Nude Paradise) and Sutorippu Tokyo.

Of more interest for our purposes is Shimura Toshio's Nikutai no hakusho (White paper of the Flesh). It was the first film by Shin'eigasha, a production company founded in May 1950 by Shino Katsuzo, the former vice-director and head of the planning department of the Oizumi Studio. He quit the studio after internal troubles and set up his own production company located within the Oizumi Studio compound. Director Shimura Toshio originally came from Toho (after the second Toho strike he changed to Shintoho), and so did Yamamoto Kajiro who wrote the screenplay together with Takayanagi Haruo. The screenplay was based on Ibuki Chikashi's Nikutai no hakusho - Yoshiwara byoin kiroku (White paper of the Flesh - Yoshiwara Hospital Report), documenting life in the Yoshiwara red light district. Ibuki was the head of the Yoshiwara Hospital (most likely the hospital Koito Nobu visited when doing research for her novel Otome no seiten) and wrote several studies on the situation of the prostitutes in Yoshiwara. In 1953 the publisher Bungei Shuppan published his book Baishunfu no seiseikatsu (The Sex Life of Prostitutes) as the second volume of their series Nihon ni okeru sei no chosa hokoku daishu (Grand Collection of sex survey reports in Japan). The first volume was Okada Toraji's Shishunki no seiishiki (Sexual consciousness of adolescence). From his writings Ibuki's advocacy of sex education and his position as social educator if not sex educator becomes evident. How much of this is reflected in Shimura's Nikutai no hakusho is debatable. A Naigai Times report about the filming, which took place on location at the Yoshiwara Hospital and within Yoshiwara, describe the film as "semi-documentary", but contemporary reviews objected to the film's "sensationalism" and classified it as "panpan eiga" (hooker film), a "genre" very much in fashion at the time.

Mori Kazuo's Daiei film Aru fujinka-i no kokuhaku (Confession of a gynaecologist), written by Yoda Yoshikata and produced by Minoura Jingo (who at the same time worked with Kurosawa Akira on Rashomon), also revolved around a gynaecologist and the problem of unwanted pregnancy, abortion and sex. "Sei to ninshin no mondai" (The problem of Sex and Pregnancy) was also the film's slogan. Aru fujinka-i no kokuhaku was released together with the two-reel short Datai (Abortion), an educational film about the Eugenic Protection Law (yusei hogoho) which was passed in July 1948 regulating abortion.

A third "doctor film" should be mentioned, Joi no shinsatsushitsu (Examination room of a female doctor), produced by Takimura Production and directed by Yoshimura Ren, a Nikkatsu/Daiei director on a brief break-away from his studio. Takimura Production was established in June 1949 by former Toho producer Takimura Kazuo who had left Toho during the second Toho strike. Takimura Production also produced Mizoguchi's Yuki fujin ezu mentioned above. I mention Joi no shinsatsushitsu not because of Hara Setsuko and Uehara Ken who play the lead roles in this love story, but because of Tsuneyasu Tazuko who wrote the original story on which the film is based. Her book of the same title was published in December 1948 by Kokumin kyoikusha. Tsuneyasu, a doctor by profession and a prolific writer, authored several books which could be classified as "sex education books" or "sex advisories" such as Kekkon ni wa mada hayai - Joi no sodanshitsu (Too young for marriage - Consultation room of a female doctor; Anka shobo, 1955) and Shishunki no seiten - Kokosei to joi no taiwa (Sex encyclopedia of puberty - Conversation between high school pupils and a female doctor; Hobunsha 1955).

Several of her books were used for film adaptations such as Hagiyama Teruo's Jogakusei no techo - Otome no mezame (Awakening of a maiden; Shochiku 1953) and Nakaki Shigeo's Judai no himitsu (Teenager Secrets; Daiei, 1954) - both, by the way, late examples of the second seiten eiga boom that will be discussed in part 4 of the series - or Mesu o motsu shojo (Virgin holding a knife; Toho, 1951). The latter was based on Tsuneyasu's book Joshi igakusei (Female medical student) published in 1949. The film starred Sugi Yoko, who since her debut in the Toho smash hit Aoi sanmyaku (Blue mountains, 1949) was one of Japan's leading young actresses, and Izu Hajime. On a side note, in 1964 actor Izu Hajime directed a film with the title Onna (Woman) starring Hoshi Michiko (who had started her career with the above mentioned Nikutai no hakusho). The film was produced by Kokuei and is an early example of the pink eiga genre that began to gain ground at that time (one of the founders and veterans of the pink eiga genre, by the way, was the producer of Mesu o motsu shojo, Motogi Sojiro). Mesu o motsu shojo was directed by Oda Motoyoshi, a reliable, but not particularly distinguished director. Some critics consider two of his films directed in 1950, Jogakuseigun (A group of schoolgirls) and Zoku furyo shojo (Delinquent girls Part 2), as "seiten eiga" in a more general sense. Futaba Juzaburo for instance labelled Jogakuseigun as "seiten eiga no hanpamono" (remnant seiten film). Zoku furyo shojo was, as the title suggests, a sequel. It followed Naruse Mikio's Furyo shojo (Delinquent girls) which like Jogakuseigun was based on a novel by "nikutai-ha" writer Tamura Taijiro, a highly successful author typical for Japan's post-war literature. More than a dozen of his books were made into films, some of them several times like his most famous novel Nikutai no mon (Gate of Flesh). In 1966 Tamura himself made a brief foray into film when he directed one episode of the omnibus film Nihon o shikaru - shatta O (Scolding Japan - Shutter O). Furyo shojo tells the story of two former classmates, Tamie and Eiko, one of whom leads a decent life while the other degenerates. The film was produced by Toyoko Eiga and released by Shochiku in March 1949. During the third Toho strike Naruse followed Kurosawa Akira and joined Eiga Geijutsu Kyokai, the production company set up by Yamamoto Kajiro and producer Motogi Sojiro who also produced Furyo shojo. The film got only mediocre reviews and Naruse himself did not rate the film very highly, but at the end of his life cinematographer Tamai Masao remembered the film as a "hidden masterpiece" (kakureta kasaku), a judgement difficult to verify, because Furyo shojo is Naruse's only post-war film which has been lost. Naruse made Furyo shojo after he began working on Shiroi yaju (White beast), but the third Toho strike got under way during the shooting and Naruse had to wait two years until he could finish this film about a group of prostitutes in a rehabilitation facility struggling with social prejudices, unwanted pregnancies and venereal diseases. Naruse had to cope not only with the forced stop of the shooting, but also with the loss of his lead actress Miura Mitsuko, who in the meantime had married an officer of the occupation forces and had followed him to the United States. Naruse had to rewrite the script, add additional characters to cover up missing scenes with Miura and straighten out the differences of a quickly changing time.

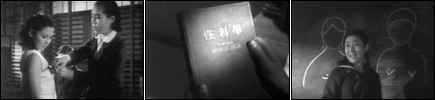

Another film by Naruse needs to be mentioned here, because in a way it heralded the seiten films and because sex education plays an important role in it. The film is Haru no mezame (Spring Awakening), Naruse's third post-war film. The title, of course, refers to Frank Wedekind's famous play Frühlingserwachen, which enjoyed great popularity in Japan before the war (three translations by Shibata Sakuji, Nogami Toyoichiro and Kando Takanori respectively were published in 1925 alone, a fourth by Kawahara Mankichi followed in 1927). Conceived in 1946, the film had to wait for a year, because of the first Toho strike and other difficulties. The film revolves around Kumiko, a high school third grader played by Kuga Yoshiko in her second film. During a visit at her classmate Hanae's home she meets Hanae's elder brother Koji for whom she begins to develop tender feelings. But her world is turned upside down when she learns that her classmate Akiko is pregnant and that Tomie, her family's maid, got fired after her parents had found out that Tomie had a boyfriend; they had been afraid Tomie might set her a bad example. Koji also struggles with his feelings for Kumiko, but finds comfort with his liberal and understanding father, a doctor, who gives him a book about sex education and invites him to come to him whenever he has a question. Kumiko on the other hand has no one to turn to and shows signs of distress. When Koji's father calls on the girl to examine her he lectures her parents that it is the duty of parents to (sexually) educate their children and to give them encouragement during their adolescence when they are particularly vulnerable emotionally. The film ends on a positive note: the young people decide not to rush things but see how their feelings for each other develop. In a prominent scene Koji's father, played by Shimura Takashi, gives his son a book titled Seikagaku (Sexual science). This title of the prop book is clearly legible, whereas the author's name is indecipherable. The book perhaps points to Ota Takeo's Seikagaku published in 1937 by Mikasa Shobo as vol. 26 of its "Yuibutsuron zenshu" (Materialism treatise) series. [Iwasaki Akira's Eigaron (On film) was also published in this series]. In April 1948, six months after the release of Haru no mezeme, Mikasa Shobo published a new edition of the book. By that time the author had changed his first name to Tenrei.

One last film must be mentioned and this is Wakabito e no hanamuke (Farewell present to young people), made after a script written by Azumi Yoshihito, the director of the Heian Hospital in Kyoto specializing in venereal diseases. I mention this typical sex education film because on March 22, 1950, three days after the opening of Otome no seiten, an article in the Miyako Shinbun labels the film project as "wakabito no seiten" (sex encyclopedia for young people).

In conclusion one can say that the explicit treatment of sex education made its entrance into Japanese mainstream cinema as early as 1947 in Naruse's Haru no mezame. The commercial success of Otome no seiten in spring 1950 resulted in a couple of follow-ups by the languishing studio Shochiku and established the term "seiten eiga" in the media where it was soon corrupted and used to denote not only films related to sex education in particular, but films of a more or less explicit sexual or erotic nature in general. The heterogeneity of the films, however, doesn't allow us to speak of a seiten eiga boom. In fact, the films made in 1950 can be seen as just a prelude for the real seiten eiga boom that hit Japanese cinemas two years later. This second and larger group of seiten eiga films, which will be discussed in part 4 of the series, was triggered by the success of the Italian film Domani è troppo tardi (Tomorrow is too late, 1950), whose title sounded like a warning in the ears of the Japanese film studios' executives.

(Note: all names in this essay are in Japanese order: family name first, given name second.)